Finnish literature

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2012) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Finland |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Reformation-era literature |

|---|

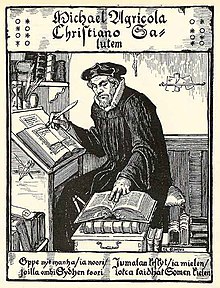

Finnish literature refers to literature written in Finland. During the European early Middle Ages, the earliest text in a Finnic language is the unique thirteenth-century Birch bark letter no. 292 from Novgorod. The text was written in Cyrillic and represented a dialect of Finnic language spoken in Russian Olonets region. The earliest texts in Finland were written in Swedish or Latin during the Finnish Middle Age (c. 1200–1523). Finnish-language literature slowly developed from the sixteenth century onwards, after written Finnish was established by the bishop and Finnish Lutheran reformer Mikael Agricola (1510–1557). He translated the New Testament into Finnish in 1548.

After becoming a part of the Russian Empire in the early nineteenth century the rise in education and nationalism promoted public interest in folklore in Finland and resulted in an increase of literary activity in Finnish. Most of the significant works of the era, written in Swedish or increasingly in Finnish, revolved around achieving or maintaining a strong Finnish identity (see Karelianism). Thousands of folk poems in what came to be called Kalevala meter were collected in Suomen kansan vanhat runot (The ancient poems of the Finnish people). The most famous poetry collection is the Kalevala, published in 1835. The first novel published in Finnish was Seven Brothers (1870) by Aleksis Kivi (1834–1872). The book Meek Heritage (1919) by Frans Eemil Sillanpää (1888–1964) made him the first Finnish Nobel Prize winner. Another notable author is Väinö Linna.

Other works known worldwide include Michael the Finn and The Sultan's Renegade (known in the USA as The Adventurer and The Wanderer, respectively) by Mika Waltari (1908–1979). Beginning with Paavo Haavikko and Eeva-Liisa Manner, Finnish poetry in the 1950s adapted the tone and approach of T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. The most famous poet was Eino Leino. Timo K. Mukka (1944–1973) was the wild son of Finnish literature. Prominent writers of the twenty-first century include Mikko Rimminen and sci-fi authors Leena Krohn (Finlandia Prize 1992) and Johanna Sinisalo (Finlandia Prize 2000).

Pre-nineteenth century

[edit]

During the European early Middle Ages, what is now Finland was a sparsely populated area characterised by pre-state societies. It was gradually absorbed into the emergent states of Sweden and, to a lesser extent, Russia. There is almost no Finnish-language literature from the Middle Ages or earlier; the earliest text in a Finnic language is the unique thirteenth-century Birch bark letter no. 292 from Novgorod. The text was written in Cyrillic and represented a dialect of Finnic language spoken in the Russian Olonets region. Books such as the Bible and Code of Laws were only available in Latin, Swedish or a few other European languages such as French or German. The understanding of the medieval circulation of these non-Finnish writings in what is now Finland has been growing since the National Library of Finland digitised its medieval Fragmenta membranea.[1]

Written Finnish was established by Bishop and Finnish Lutheran reformer Mikael Agricola (1510–1557), who based it mainly on western dialects. His main works are a translation of the New Testament (completed in 1548) and a primer, Abckiria, in Finnish. The first translation of the entire Bible was published in 1642.[2] The first grammar of Finnish was published by Aeschillus Petraeus in 1649, and includes eight Finnish riddles. Another major step towards developing a written vernacular literature came with the work of Cristfried Ganander, who published over 300 riddles in 1783.

Until 1800, most of the literature published in Finnish was religious.[3]

Nineteenth century

[edit]

After becoming a part of the Russian Empire, known as the Grand Duchy of Finland, in the early nineteenth century, Finland saw a rise in education, and nationalism promoted public interest in folklore and resulted in increasing literary activity in the Finnish language. This was characterised by an explosion in the collection and study of folklore in Finland, with a particular emphasis on Finnish-language material. Much of this material is widely thought to originate in the Middle Ages, and is often thought of in Finland as medieval literature, although this is a problematic claim.[4] Much also came from Karelia, which also being a part of Russia contributed to the creation of Finnish literature. These folklore-collecting efforts were to a large extent co-ordinated by the Finnish Literature Society, founded in 1831. Hundreds of old folk poems, stories and their like have been collected since the 1820s into a collection which is among the largest in the world. Many of these have since been published as Suomen kansan vanhat runot ('The Ancient Poems of the Finnish People'), a colossal collection consisting of 27,000 pages in 33 volumes. The prominence of folklore in nineteenth-century Finland made Finnish scholarship world-leading in that area at the time; thus for example the internationally used Aarne–Thompson classification system for folktale narratives originated in Finnish scholarship.

The most famous collection of folk poetry is by far the Kalevala. Referred to as the Finnish "national epic" it is mainly credited to Elias Lönnrot, who compiled the volume. It was first published in 1835 and quickly became a symbol of Finnish nationalism. Finland was then politically controlled by Russia and had previously been part of Sweden. The Kalevala was therefore an important part of early Finnish identity. Beside the collection of lyric poems known as the Kanteletar it has been and still is a major influence on art and music, as in the case of Jean Sibelius. It is a common misconception that Lönnrot merely "collected" pre-existing poetry. It is now widely accepted that the Kalevala represents an amalgam of loosely connected source materials, freely altered by Lönnrot to present the appearance of a unified whole.

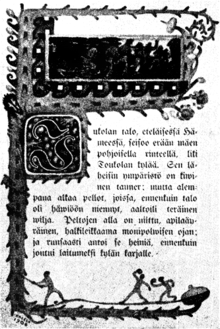

The first novel published in Finnish was Seven Brothers (1870) by Aleksis Kivi (1834–1872), still generally considered to be one of the greatest of all works of Finnish literature. As in Europe and the United States, the popularity of the novel in Finland is connected to industrialisation, as are many of the first Finnish novels that deal with the life of the modern middle-class or the clash of the traditional peasants with developments such as the railway. Specifically, the theme of Seven Brothers concerns uneducated residents of the countryside and the struggle to survive under the new authority of the developing urban civilisation - a common theme in Finnish novels.[5][6]

Among Finland's prominent female writers in the nineteenth century was Minna Canth (1844–1897), best known for her plays Työmiehen vaimo (The Worker's Wife) and Anna Liisa.[7]

Twentieth century

[edit]At the end of the Grand Duchy of Finland, literature consisted largely of romance and drama, such as novel The Song of the Blood-Red Flower (1905) by Johannes Linnankoski (1869–1913), but then Finland gained its independence in 1917 and soon after a civil war broke out. As with other civil wars it was to be depicted many times in literature, as in Meek Heritage (1919) by Frans Eemil Sillanpää (1888–1964). Sillanpää was a strong leader of literature in the 1930s in Finland and was the first Finnish Nobel Prize winner.[8] The theme was taken up by Väinö Linna (1920–1992), already phenomenally successful because of his novel The Unknown Soldier (1954).[9] In this and other cases the very strangeness of the Finnish environment and mentality have been major obstacles to international renown.

Other works known worldwide include Michael the Finn and The Sultan's Renegade (known in the US as The Adventurer and The Wanderer respectively) by Mika Waltari (1908–1979). The Egyptian (Sinuhe egyptiläinen, 1945), partially an allegory of the Second World War but located in ancient Egypt, is his best known work. Despite containing nearly 800 pages, no other book has sold so fast in Finland and the shorter English version was atop many best-seller lists in the US.[10] One possible reason for their international success is their focus on post-war disillusionment, a feeling shared by many at the time.

Beginning with Paavo Haavikko and Eeva-Liisa Manner, Finnish poetry in the 1950s adapted the tone and level of the British and American – T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound were major influences and widely translated. Traditionally German and especially French literature have been very well known and sometimes emulated in Finland. Paradoxically the great Russian tradition might have been less known, possibly because of a political aversion.

The most famous poet was Eino Leino – who in addition to his own writing was also a proficient translator of, among others, Dante.[11] Otto Manninen was a master of meters and translated both the Iliad and Odyssey by Homer. After the wars Pentti Saarikoski might initially have been a counterpart of the beat generation, but being well educated, he translated Homer, James Joyce and many important English and American writers.[12]

Timo K. Mukka (1944–1973) was the wild son of Finnish literature. During a period of less than a decade in the 1960s, Mukka sprang virtually from nowhere to produce nine novels written in a lyrical prose style. His two greatest masterpieces are the novel The Song of the Children of Sibir and the novella The Dove and the Poppy – after which he ceased writing until his early death.

Twenty-first century

[edit]After a successful year as the Guest of Honor at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2014, Finland was able to rebrand itself – internationally, too – as a literary country. "Obscurity became Finland's calling card", writes Kalle Oskari Mattila in The Paris Review, noting that, "Finland had largely fallen off the trend of Nordic noir and crime writing, but that exclusion provided a new kind of branding opportunity: ambitious literary fiction".[13]

By 2018, Finnish literary exports had more than tripled in size. Anglo American markets have surpassed Germany as the leading source of export revenue.[13]

Prominent writers of this century include Sofi Oksanen, Pajtim Statovci, Laura Lindstedt and Mikko Rimminen, noted for his irreverent portrayals of life in Helsinki and winner of the 2011 Finlandia Prize. Finnish writing has also become internationally noted for its fantasy and science fiction, having gained momentum in the late twentieth century, partly through a thriving fandom scene. Leading exponents include Leena Krohn (Finlandia Prize 1992) and Johanna Sinisalo (Finlandia Prize 2000).

Swedish-language literature

[edit]A strong Swedish-language literature emerged in Finland only in the nineteenth century.[2] Before this, Jacob Frese (1690–1729) was a noted Swedish-language poet who was born in Finland and fled to Stockholm after the Russian occupation of his hometown Vyborg (Viipuri in Finnish).[14] Known for his baroque poetry often containing religious themes,[14] he considered himself a refugee from Finland[15] and emphasized his Vyborg and Finnish roots in different ways.[14] His poem "Echo å Sweriges Allmänne Frögde-Qwäden" (1715), part of which is dedicated to his hometown, has been called "the first work in which a Finn expressed his patriotism and love for his native country" since the Greek poem Magnus Principatus Finlandia by Johan Lillienstedt.[15] Another well-known Finnish poet who wrote in Swedish while the country was still part of Sweden was Frans Michael Franzén (1772–1847). He was considered an innovator in his youth, when adherence to classical French conventions was still very strong. He moved to Sweden in 1811, two years after the Russian annexation of Finland.[16]

Even after the establishment of Finnish as the primary language of administration and education, Swedish remained important in Finland.

Johan Ludvig Runeberg (1804–1877) was the most famous Swedish-speaking writer of the nineteenth century. The opening poem Our Land (from The Tales of Ensign Stål) was dedicated as the national anthem as early as seventy years before Finnish independence. During the early 20th century, the Swedish-language modernism emerged in Finland as one of the most acclaimed literal movements in the history of the country. The best-known representative of the movement was Edith Södergran.

The most famous Swedish-language works from Finland are probably the Moomin books by writer Tove Jansson. They are also known in comic strip or cartoon forms. Jansson was, however, only one of several Swedish-language writers for children whose work can be understood as part of a wave of innovative 1960s–1970s Nordic-language children's writing; another leading Finnish exponent was Irmelin Sandman Lilius.

Other prominent twentieth-century Swedish-language writers of Finland are Henrik Tikkanen and Kjell Westö, both noted for their often (semi)-autobiographical realist novels. The rise of Finnish-language fantasy and science fiction has been paralleled in Swedish, for example in the work of Johanna Holmström.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Heikkilä, Tuomas (2010). "Kirjallinen kulttuuri keskiajan Suomessa, Historiallisia tutkimuksia 254". Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ a b Zuck, Virpi; Laitinen, Kai L.K. (5 August 2008). "Finnish literature". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Wiegand, Wayne A.; Davis, Donald G. Jr. (1994). Encyclopedia of Library History. Garland Publishing. ISBN 9781135787578. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Cf. Derek Fewster, Visions of Past Glory: Nationalism and the Construction of Early Finnish History. Studia Fennica Historica 11 (Helsinki: Suomalainen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2006).

- ^ Sihvo, Hannes. "Kivi, Aleksis (1834 - 1872)". The National Biography of Finland. SKS. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ "Juhani Aho". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Krogerus, Tellervo. "Canth, Minna (1844 - 1897)". The National Biography of Finland. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Rajala, Panu. "Sillanpää, Frans Emil (1888 - 1964)". The National Biography of Finland. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Nummi, Jyrki. "Linna, Väinö (1920 - 1992)". The National Biography of Finland. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Envall, Markku. "Waltari, Mika (1908 - 1979)". The National Biography of Finland. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Nevala, Marja-Liisa. "Leino, Eino (1878 - 1926)". The National Biography of Finland. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Pentti Saarikoski (1937-1983) - wrote also humorous columns under the name 'Nenä' (the nose); see Gogol". Authors' Calendar. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ a b Mattila, Kalle Oskari (16 July 2018). "How Finland Rebranded Itself as a Literary Country". The Paris Review Daily. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Tarkiainen, Kari (December 2014) [Original print version in 2008]. "Frese, Jacob". Biografiskt lexikon för Finland (in Swedish). Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ a b Ahokas, Jaakko (1973). A History of Finnish Literature. Indiana University, Bloomington. pp. 24–26.

- ^ Ahokas 1972, p. 29

Further reading

[edit]- Paavolainen, Nina; Kantokorpi, Mervi; Antas, Maria. "Finnish Contemporary Literature: A Wealth of Voices". This Is Finland. Finland Promotion Board. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- Schoolfield, George C., ed. (1998). A History of Finland's Literature. Histories of Scandinavian Literature. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4189-3.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch