Baa, Baa, Black Sheep

| "Baa, Baa, Black Sheep" | |

|---|---|

Sheet music | |

| Nursery rhyme | |

| Published | c. 1744 |

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional |

"Baa, Baa, Black Sheep" is an English nursery rhyme, the earliest printed version of which dates from around 1744. The words have barely changed in two and a half centuries. It is sung to a variant of the 18th century French melody Ah! vous dirai-je, maman.

Modern version[edit]

The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes gives the following modern version:[1]

Baa, baa, black sheep,

Have you any wool?

Yes, sir, yes, sir,

Three bags full;

One for the master,

And one for the dame,

And one for the little boy

Who lives down the lane.

The rhyme is a single stanza in trochaic metre, common in nursery rhymes and relatively easy for younger children.[2][3] The Roud Folk Song Index classifies the song as 4439; variants have been collected across Great Britain and North America.[4]

Melody[edit]

The rhyme is sung to a variant of the 18th century French melody Ah! vous dirai-je, maman,[1] also used for "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star", "Little Polly Flinders", and "Alphabet song". The words and melody were first published together by A. H. Rosewig in (Illustrated National) Nursery Songs and Games, published in Philadelphia in 1879.[5]

The text was translated to Swedish by August Strindberg for Barnen i skogen (1872), a Swedish edition of Babes in the Wood. To this Swedish text a melody was written by Alice Tegnér for publication in the songbook Sjung med oss, Mamma! (1892). Bä, bä, vita lamm, in which the black sheep is replaced with a white lamb, has become one of the most popular Swedish children's songs.[6]

Origin and meaning[edit]

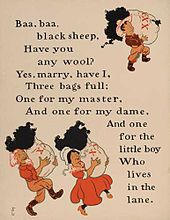

The rhyme was first printed in Tommy Thumb's Pretty Song Book of about 1744, with words very similar to the modern version:

Bah, Bah, a black Sheep,

Have you any Wool?

Yes merry have I,

Three bags full,

One for my Master,

One for my Dame,

One for my Little Boy

That lives in the lane.[1]

In the next surviving printing, in Mother Goose's Melody (c. 1765), the text remained the same, except the last lines, which were given as, "But none for the little boy who cries in the lane".[1]

As with many nursery rhymes, attempts have been made to find origins and meanings for the rhyme, most of which have no corroborating evidence.[1] Katherine Elwes Thomas in The Real Personages of Mother Goose (1930) suggested the rhyme referred to resentment at the heavy taxation on wool.[7] This has been taken to refer to the medieval English "Great" or "Old Custom" wool tax of 1275, which survived until the fifteenth century.[1] More recently the rhyme has been alleged to have a connection to the slave trade, particularly in the southern United States.[8] This explanation was advanced during debates over political correctness and the use and reform of nursery rhymes in the 1980s, but has no supporting historical evidence.[9] Rather than being negative, the wool of black sheep may have been prized as it could be made into dark cloth without dyeing.[8]

Modern controversies[edit]

In 1986 the British popular press reported a controversy over the rhyme's language, suggesting that "black" was being treated as a racial term. This was based on a rewriting of the rhyme in one private nursery as an exercise for the children there.[10] A similar controversy emerged in 1999 when reservations about the rhyme were submitted to Birmingham City Council by a working group on racism in children's resources.[11] Two private nurseries in Oxfordshire in 2006 altered the song to "Baa Baa Rainbow Sheep", with "black" being replaced with a variety of other adjectives such as "happy", "sad", "hopping" and "pink".[12] Commentators have asserted that these controversies have been exaggerated or distorted by some elements of the press as part of a general campaign against political correctness.[10]

In 2014, there was reportedly a similar controversy in the Australian state of Victoria.[13]

Allusions[edit]

The phrase "yes sir, yes sir, three bags full sir" has been used in reference to a obsequious or craven subordinate. It is attested from 1910, and originally was common in the British Royal Navy.[14]

The rhyme has often appeared in literature and popular culture. Rudyard Kipling used it as the title of an 1888 semi-autobiographical short story.[7] The name Black Sheep Squadron was used for the Marine Attack Squadron 214 of the United States Marine Corps from 1942 and the title Baa Baa Black Sheep was used for a book by its leader Colonel Gregory "Pappy" Boyington and for a TV series (later syndicated as Black Sheep Squadron) that aired on NBC from 1976 until 1978.[15] In 1951, together with "In the Mood", "Baa Baa Black Sheep" was the first song ever to be digitally saved and played on a computer.[16]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Opie, I. & Opie, P. (1997) [1951]. The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-19-860088-7.

- ^ Hunt, P. (1997). International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 0-2031-6812-7.

- ^ Opie, Iona (2004). "Playground rhymes and the oral tradition". In Hunt, Peter (ed.). International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. p. 276. ISBN 0-415-29055-4.

- ^ "Searchable database" Archived 2014-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, English Folk Song and Dance Society, retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ J. J. Fuld, The Book of World-Famous Music: Classical, Popular, and Folk (Courier Dover Publications, 5th edn., 2000), ISBN 0-486-41475-2, pp. 593-4.

- ^ Bä, bä, vita lamm, page 10, in Alice Tegnér, Sjung med oss, Mamma! (1892), found in Project Runeberg.

- ^ a b W. S. Baring-Gould and C. Baring Gould, The Annotated Mother Goose (Bramhall House, 1962), ISBN 0-517-02959-6, p. 35.

- ^ a b "Ariadne", New Scientist, 13 March 1986.

- ^ Lindon, J. (2001). Understanding Children's Play. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes. p. 8. ISBN 0-7487-3970-X.

- ^ a b Curran, J.; Petley, J.; Gaber, I. (2005). Culture wars: the media and the British left. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 85–107. ISBN 0-7486-1917-8.

- ^ Cashmore, E. (2004). Encyclopedia of Race and Ethnic Studies. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 321. ISBN 0-415-28674-3.

- ^ "Nursery opts for "rainbow sheep"". BBC News Education. 7 March 2006. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- ^ "Racial connotations over black sheep prompts changes to Baa Baa Black Sheep at Victorian kindergartens". Herald Sun. 17 October 2014. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ^ Partridge, Eric; Beale, Paul (1986). A dictionary of catch phrases: British and American, from the sixteenth century to the present day (2nd revised & abridged ed.). Routledge. p. 547. ISBN 0-415-05916-X.

- ^ F. E. Walton, Once They Were Eagles: The Men of the Black Sheep Squadron (University Press of Kentucky, 1996), ISBN 0-8131-0875-6, p. 189.

- ^ J. Fildes, "Oldest computer music unveiled", BBC News, retrieved 15 August 2012.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch