Battle of Verneuil

| Battle of Verneuil | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

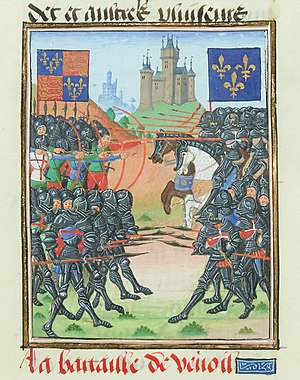

Illumination from La Cronicque du temps de Tres Chrestien Roy Charles, septisme de ce nom, roy de France by Jean Chartier, c. 1470–1479 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of France Kingdom of Scotland Supported by: Duchy of Milan | Kingdom of England | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Count of Aumale † Earl of Douglas † Earl of Buchan † Viscount of Narbonne † | Duke of Bedford Earl of Salisbury | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 14,000–16,000[2] | 8,000–9,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 6,000 killed[4] 200 captured | 1,600 killed[5] | ||||||

Location within Normandy | |||||||

The Battle of Verneuil was a battle of the Hundred Years' War, fought on 17 August 1424 near Verneuil-sur-Avre in Normandy between an English army and a combined Franco-Scottish force, augmented by Milanese heavy cavalry. The battle was a significant English victory, and was described by them as a second Agincourt.

The battle started with a short archery exchange between English longbowmen and Scottish archers, after which the force of 2,000 Milanese heavy cavalry charged the English, brushed aside an ineffective English arrow barrage and wooden archer's stakes, penetrated the formation of English men-at-arms and routed one wing of their longbowmen. The Milanese pursued the fleeing English off the field and went on to capture and loot the English baggage train. Meanwhile, the well-armoured English and Franco-Scottish men-at-arms clashed on foot in a ferocious hand-to-hand melee that went on for about 45 minutes. Many of the English longbowmen rallied and joined the struggle. The French men-at-arms eventually routed, leaving the Scots alone in a last stand where they received no quarter from the English. The Milanese cavalry returned to the field at the end of the battle but fled upon discovering the fate of the Franco-Scottish force.

Altogether some 6,000 French and Scottish were killed and 200 taken prisoner.[6][7] The Burgundian chronicler Jean de Wavrin, who fought in the battle, estimated 1,600 English killed, although the English commander, John, Duke of Bedford, claimed to have lost only two men-at-arms and "a very few archers". The Scots army, led by the earls of Douglas and Buchan (both of whom were killed in the battle), was almost destroyed. Many French nobles were taken prisoner, among them the Duke of Alençon and the Marshal de La Fayette. After Verneuil, the English were able to consolidate their position in Normandy. The Army of Scotland as a distinct unit ceased to play a significant part in the Hundred Years' War, although many Scots remained in French service.

Background[edit]

In 1424, France was still recovering from the 1415 disaster at Agincourt, and the northern provinces were in the hands of the English following Henry V's conquest of Normandy. The Dauphin (heir to the French throne) Charles had been disinherited due to the 1420 Treaty of Troyes and, upon the death of his father Charles VI in October 1422, his status as King of France was recognised only in the regions still not occupied by the English, namely the south of the country (less the province of Guyenne in the southwest).[8] The civil war between the pro-Dauphin Armagnacs and the pro-English Burgundians showed no sign of ending.[citation needed]

The death of Henry V in August 1422, two months before that of Charles VI, brought no relief to the French, as the continuing English war effort was managed by Henry's brother Bedford, acting for the nine-month-old Henry VI.[9] The Dauphin desperately needed soldiers, and looked to Scotland, France's old ally, to provide essential military aid.[10]

Army of Scotland[edit]

The first large contingent of Scots troops came to France in the autumn of 1419, some 6,000 men under the command of John Stewart, Earl of Buchan.[11] These men, strengthened from time to time by fresh volunteers, soon became an integral part of the French war effort, and by the summer of 1420 the "Army of Scotland" was a distinct force in the French royal service. They proved their worth the following year, playing a large part in the victory at the Battle of Baugé, the first serious setback experienced by the English.[12] The mood of optimism this engendered collapsed in 1423, when many of Buchan's men fell at the Battle of Cravant.[citation needed]

At the beginning of 1424, Buchan brought with him a further 6,500 men. He was accompanied by Archibald, Earl of Douglas, one of the most powerful noblemen of Scotland. On 24 April, the army, comprising 2,500 men-at-arms and 4,000 archers, entered Bourges, the Dauphin's headquarters, helping to raise Charles' spirits. A body of 2,000 heavy cavalry was hired from Filippo Maria Visconti, the Duke of Milan, after a treaty of alliance on 17 February. These men-at-arms were led by the Frenchman le Borgne-Caqueran and clad in complete suits of tempered steel plate armour, and rode barded horses.[13] A smaller Milanese cavalry force had been decisive against the Burgundians at La Buissière in September 1423.[14][13]

The victory at La Buissière and an English defeat by the French under the Count of Aumale at the Battle of La Brossinière on 26 September 1423 improved the Dauphin's strategic situation.[15][16] The outflanking and destruction of a body of English longbowmen at La Brossinière convinced the French that it would be possible to destroy a large English army in a decisive battle.[17][16] A plan was devised – the main English army would be sought out and crushed, after which Charles VII would be crowned as king in Reims.[16]

Army of France[edit]

The French army was under the command of the Count of Aumale, a French commander who had defeated the English at La Brossiniere and the Burgundians at Le Buissiere. He was accompanied by the Viscount of Narbonne, and their army joined with the Scots under the Earl of Buchan. Thus reinforced, the Franco-Scottish army was confident it could fight the English and yet again secure a great victory as at Baugé.[citation needed]

Prelude[edit]

In the summer of 1424 the English army, under the command of Bedford and the experienced Earl of Salisbury, laid siege to the French stronghold of Ivry, 42 km (26 miles) northeast of Verneuil.

The Franco-Scottish army made ready to march to Ivry and lift the siege of the castle, and Buchan left Tours on 4 August to meet with Aumale and Narbonne. But before the army could reach the castle, it surrendered to the English. Uncertain what to do, the allied commanders held a council of war.[18] The Scots and some of the younger French noblemen were eager for battle, but Narbonne and the senior nobility had not forgotten Agincourt and were reluctant to take the risk.[18] As a compromise it was agreed to attack the English strongholds on the Norman border, beginning with Verneuil in the west.[18] The town was taken by a simple ruse: A group of Scots, leading some of their fellow countrymen as prisoners, pretended to be English, and claimed that Bedford had defeated the allies in battle, whereupon the gates were opened.[19]

On 15 August, Bedford received news that Verneuil was in French hands and he and his army marched there as quickly as they could.[20][21] As he neared the town two days later, the Scots persuaded their French comrades to give battle. Douglas is said to have received a message from Bedford that he had come to drink with him and prayed for an early meeting. He replied that having failed to find the duke in England he had come to seek him in France.[22]

On 16 August, Bedford dismissed the Burgundian commander L’Isle Adam and his 1000-2000 man contingent sending them back to the siege at Nesle in Picardy. Bedford depriving his army of so many men just prior to battle has been a confusing decision for historians to explain, though some cite a growing lack of trust between the English and Burgundians.[23]

Battle[edit]

Dispositions[edit]

The Franco-Scottish army deployed a mile north of Verneuil on an open plain astride the road leading out of the forest of Piseux. The flat fields had been chosen to give the greatest advantage to the Milanese cavalry, where they could be employed to their full potential against the enemy archers.[24] The mounted Milanese men-at-arms under Caqueran drew up in front of the dismounted Franco-Scottish men-at-arms, who were formed into one battle.[25] Narbonne's Spanish mercenary men-at-arms and most of the French were situated on the left of the road, while Douglas and Buchan were on the right. Aumale was given overall command, but this heterogeneous army defied all attempts at coordinated direction.[26]

On emerging from the forest, Bedford likewise put his men in a single battle, to match the disposition of the enemy, with the usual distribution of men-at-arms in the centre and archers on the wings and in front, with sharpened stakes ahead of them.[27] Bedford placed a lightly-armoured rearguard of 500–2,000 men, some mounted, to protect the baggage train and the horses.[28][29] Some 8,500 horses were tethered together to link the main army to the baggage wagons as a precaution against encirclement.[29]

Both sides wanted the other to take the initiative in beginning the battle, and so, from dawn to about 4:00 pm, the two armies stood facing each other under the blazing sun.[30] Bedford is also said to have sent a herald to Douglas once both armies had been deployed to ask what terms for battle he required, to which Douglas grimly replied that the Scots would neither give nor receive any quarter.[31]

Milanese attack[edit]

At about 4 pm, Bedford ordered his men to advance.[30] The English soldiers shouted "St. George! Bedford!" as they slowly began to cross the field.[30] A short archery duel between English and Scottish archers took place, with inconclusive results. At the same time, as if by some pre-arranged signal, the 2,000 Milanese mounted men-at-arms charged the English front line.[32][30] They brushed aside the English wooden stakes that could not be secured in ground baked hard by the summer sun.[33] English arrows proved ineffective against the Italian mercenaries' superior armor.[33] The shock effect of the Milanese charge terrified the English, with men-at-arms and archers knocked over, and gaps torn in the English ranks as they tried to avoid the onrushing horsemen and others throwing themselves to the ground and being ridden over by the cavalry.[32][33] The Milanese rode through the entire English formation,[32][33] dispersing the longbowmen on the English right.[28][33]

Many of the English panicked in the face of the Milanese charge, and a Captain Young was afterwards found guilty of cowardice for retreating with the 500 men under his command without orders, considering the battle as lost.[34][35] Young was hanged, drawn and quartered as punishment for his retreat.[34] English mounted troops fled to Conches, where they proclaimed the battle lost to the town's small garrison.[35] At Bernay, more Englishmen announced Bedford's defeat.[35] At Pont-Audemer, news of an English disaster provoked an uprising, with retreating English troops divested of their armour and horses.[35] A series of smaller uprisings in the countryside also took place.[35]

The Milanese pursued the fleeing English and attacked the English baggage train, triggering an instant rout.[28] Some of the English rearguard ran away, fleeing on horseback or foot with the Milanese continuing to either give chase or loot the baggage train.[28]

Men-at-arms clash[edit]

After this devastating cavalry charge, Bedford rallied his soldiers, the English men-at-arms showing great discipline and reforming their ranks.[36] Sensing a victory, the French men-at-arms led a confused charge, with Narbonne's men reaching the English before the rest of their comrades. The French disorder was in part a result of the desire to close in fast to avoid English arrows.[26] As the French advanced under Aumale, they shouted "Montjoie! Saint Denis!".[30] Bedford's men-at-arms advanced in good order towards their French opponents, pausing often and giving a shout each time.[26] The men-at-arms under Salisbury were hard-pressed by the Scots.[26] A small force of French heavy cavalry on the right attempted to outflank the English line but were repelled by arrows from the redeployed English left wing of 2,000 longbowmen, who used the lines of tethered horses for cover.[37]

The head-on clash between the superbly armoured English and Franco-Scottish men-at-arms on the field of Verneuil, both of whom had marched on foot into battle, resulted, in the words of the British medievalist Desmond Seward, in "a hand-to-hand combat whose ferocity astounded even contemporaries".[30] Wavrin recalled how "the blood of the dead spread on the field and that of the wounded ran in great streams all over the earth".[30] For about three-quarters of an hour, Frenchmen, Scotsmen and Englishmen stabbed, hacked and cut each other down on the field of Verneuil without either side gaining any advantage in what is often considered to be one of the most fiercely fought battles of the entire war.[30] Bedford himself fought in the battle, wielding a fearsome two-handed poleaxe, leading one veteran to recall: "He reached no one whom he did not fell".[30] Seward noted that Bedford's poleaxe "smashed open an expensive armour like a modern tin can, the body underneath being crushed and mangled before even the blade sank in".[30]

English main attack[edit]

Many of the English longbowmen on the right, initially scattered by the Milanese charge, had by now reformed and they, along with the longbowmen on the left who had repelled the French cavalry, joined the battle. The longbowmen joined the main struggle with a great shout that boosted the morale of the English men-at-arms, who began a devastating attack on the French.[38] After some time, the French battle line gave ground before breaking and was chased back to Verneuil, where many, including Aumale, fell into the moat and were drowned. The ditches outside of town were the scene of a merciless killing of the routed French men-at-arms.[39] Narbonne and many other French nobles were killed.[40]

Having defeated the French, Bedford called a halt to the pursuit and returned to the battlefield, where Salisbury was hotly engaged with the Scots, now standing alone.[34] The battle reached its closing stages when Bedford wheeled from the south to take the Scots on the right flank. Now almost surrounded, the Scots made a ferocious last stand but were overwhelmed. The English shouted "A Clarence! A Clarence!" invoking Thomas, Duke of Clarence, Bedford's brother, killed at Baugé. The English killed any Scotsmen standing in their way; some surrendered but were slain, to avenge the death of Clarence. The long-standing enmity between Scotland and England meant no quarter was given, with almost the entire Scots force falling on the battlefield,[41][34] including Douglas and Buchan. The Milanese cavalry returned to the battle at this point to discover their comrades slaughtered, and were put to flight in their turn after losing 60 men killed. They were pursued by the English until Bedford ordered a halt allowing the Milanese to flee the field. [42]

Aftermath[edit]

Dauphin Charles was forced to postpone his plans of coronation at Reims. After Verneuil, the opportunity appeared open to take Bourges and thus bring all of France under English rule.[34] Bedford, inspired by the example of his late brother, Henry V, preferred to concentrate on completing the subjection of Maine and Anjou rather than run the risk of leading an advance into the south of France with these two provinces only partially conquered.[34] Bedford preferred to methodically conquer one province at a time rather than risk all on a bold drive to conquer the south of France in one campaign, which might finally bring all of France under English rule, but which equally might end in disaster.[34]

The consequences of the victory at Verneuil were that the English captured all border posts of Lancastrian Normandy, with the only exception being Mont Saint-Michel, where the monks resisted; La Hire, commanding another French force, withdrew to the east and a French plan to take Rouen by mining was foiled likely due to Bedford's victory.[43]

Casualties[edit]

Verneuil was one of the bloodiest battles of the Hundred Years' War, described by the English as a second Agincourt. Verneuil was a huge blow to French morale as for the second time in a decade the pride of French knighthood had met the English bowmen in battle and had been defeated.[34] Altogether some 6,000–8,000 men on the French-allied side were slain.[7][44] In a letter to Thomas Rempston written two days after the battle, Bedford stated that 7,262 allied troops were killed.[45][46][47] Bedford put his losses at two men-at-arms, and "a very few archers".[48] Wavrin, a witness to the battle, estimated 6,000 killed on the French side, 200 captured and 1,600 Anglo-Norman deaths.[7] Douglas fought on the losing side for the last time, joined in death by Buchan. Sir Alexander Buchanan, the man who had killed Clarence at Baugé three years earlier, was also killed.[citation needed]

The Army of Scotland was severely mauled but it was not yet ready to march out of history. It received far fewer reinforcements from Scotland for campaigns against the English in France.[34] This was not entirely unwelcome to the French as one French chronicler, Thomas Basin, wrote that the catastrophe at Verneuil was at least counterbalanced by seeing the end of the Scots "whose insolence was intolerable".[49] Among the prisoners were the Duke of Alençon, Pierre, the bastard of Alençon and Marshal Gilbert Motier de La Fayette. Greatly saddened by the catastrophe at Verneuil, Charles VII continued to honour the survivors, one of whom, John Carmichael of Douglasdale (Jean VI de Saint-Michel), the chaplain of the dead Douglas, was created Bishop of Orléans (1426–1438).[citation needed] Bedford returned in triumph to Paris, where "he was received as if he had been God ... in short, more honour was never done at a Roman triumph than was done that day to him and his wife".[50]

Literature and legacy[edit]

The French contemporary chronicles made long details of the reactions of the inhabitants of Paris under Burgundian rule. The Journal d'un bourgeois de Paris and Enguerrand de Monstrelet's chronicles are major sources for this battle.[51] The Chronique de Charles VII, roi de France, by the king's historian Jean Chartier (c. 1390–1464), published by Vallet de Viriville in 1858, corroborated the story of a complete English victory. The French writers bemoaned the loss of life to Charles VII's cause. Richard Ager Newhall's study of warfare in 1924 remains a reliable authority on the battle tactics and events.[52] The Victorian Rev. Stevenson translated a French study into the noble families which suffered so much in the Hundred Years' War, and is often quoted. And similarly, Siméon Luce (1833–1892), a 19th-century French medievalist historian, was transcribing from what remained of original documents in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. These secondary sources are all that are available as many of the original contemporary accounts are lost. The English had the advantage later of Burgundian Jean de Wavrin travelling with the army, but he had little to say on Verneuil.[53]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Eggenberger 1985, p. 460.

- ^ Burne 1956, pp. 213, 344.

- ^ Burne 1956, pp. 202, 212.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- ^ a b c Myers 1995, p. 234.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 109.

- ^ Wadge 2015, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 106.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 107.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 112.

- ^ a b Jones 2002, p. 391.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 150.

- ^ Wadge 2015, pp. 148, 150.

- ^ a b c Jones 2002, p. 380.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Burne 1956, p. 199.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 165.

- ^ Burne 1956, p. 200.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 167.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 171.

- ^ Wadge 2015, Chapter 12.

- ^ Barker 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Jones 2002, pp. 392, 395.

- ^ a b c d Jones 2002, p. 397.

- ^ Jones 2002, p. 395.

- ^ a b c d Jones 2002, p. 396.

- ^ a b Wadge 2015, p. 172.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Seward 2003, p. 200.

- ^ Burne 1956, p. 204.

- ^ a b c Jones 2002, p. 392.

- ^ a b c d e Wadge 2015, p. 174.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Seward 2003, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d e Jones 2002, p. 390.

- ^ Jones 2002, pp. 397, 408.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 175.

- ^ Jones 2002, pp. 396, 399.

- ^ Jones 2002, p. 399.

- ^ Burne 1956, p. 209.

- ^ Jones 2002, p. 405.

- ^ Wadge 2015, p. 183.

- ^ Barker 2012, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Neillands 2001, p. 243.

- ^ Burne 1956, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Barker 2012, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 308.

- ^ Barker 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Seward 2003, p. 202.

- ^ Barker 2012, p. 81.

- ^ Burne 1956, p. 211.

- ^ Burne 1956, p. 212.

- ^ Burne 1956, p. 223.

References[edit]

- Barker, J. (2012). Conquest: The English Kingdom of France (PDF). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06560-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2018.

- Burne, A. (1956). The Agincourt War. London: Frontline Books (published 2014). ISBN 978-1-84832-765-8.

- Eggenberger, David (1985). "Verneuil". An Encyclopedia of Battles: Accounts of Over 1,560 Battles from 1479 B.C. to the Present. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-24913-1.

- Griffiths, R.A. (1981). The Reign of King Henry VI. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04372-5.

- Jones, M.K. (1 October 2002). "The Battle of Verneuil (17 August 1424): Towards a History of Courage" (PDF). War in History. 9 (4): 375–411. doi:10.1191/0968344502wh259oa. S2CID 162319986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2019.

- Myers, A.R., ed. (28 December 1995). English Historical Documents, Volume 4: 1327–1485 (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14369-1.

- Neillands, R. (8 November 2001). The Hundred Years War (revised ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26131-9.

- Seward, D. (27 March 2003). The Hundred Years War: The English in France, 1337–1453. Brief Histories (revised ed.). London: Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84119-678-7.

- Wadge, Richard (2 February 2015). Verneuil 1424, the Second Agincourt: The Battle of the Three Kingdoms. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-6113-4.

- Wagner, J.A. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War (PDF). Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- Casavetti, Eileen (1977). The Lion and the Lilies: The Stuarts and France. Macdonald and Jane's. ISBN 978-0-354-04136-2.

- Donaldson, Gordon (1985). The Auld Alliance: The Franco-Scottish Connection. Saltire Society &. ISBN 978-0-85411-031-5.

- Forbes-Leith, William (1882). The Scots Men-at-Arms and Life-Guards in France. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: William Paterson. pp. 26–32.

- Newhall, R.A. (1924). The English Conquest of Normandy 1416–1424: a study in fifteenth century warfare. Yale historical publications. Miscellany.13. New Haven: Yale University Press. hdl:2027/uva.x000699046.

- Simpson, Martin A. (1 January 1934). "The Campaign of Verneuil". The English Historical Review. 49 (193): 93–100. doi:10.1093/ehr/XLIX.CXCIII.93. JSTOR 553429.

- Stuart, Marie W. (1940). The Scot who was a Frenchman. London: W. Hodge & Co. OCLC 6010291.

- Sumption, Jonathan (2023). Triumph and Illusion: The Hundred Years War. Vol. V (1st ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-27457-4.

- The Brut (Continuation H) – Chronicles of England

- Liber Pluscardine – Scottish chronicles from Pluscarden Abbey, Elgin

- Harleian MS 50 (BL) – Manuscript from the Robert Harley collection in the British Library

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch