Boston Central Library

| Central Library | |

|---|---|

The main entrance on Dartmouth Street | |

| Location | 700 Boylston Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02116, United States |

| Type | Research library, circulating library |

| Established | February 1895 (opened to public) |

| Architect(s) | Charles Follen McKim of McKim, Mead & White (McKim Building) Philip Johnson (Johnson Buulding) |

| Branch of | Boston Public Library |

| Other information | |

| Website | bpl.org/locations/central |

| |

| Coordinates | 42°20′58″N 71°04′41″W / 42.34944°N 71.07806°W |

| Built | 1888–1895 (McKim Building) 1969–1972 (Johnson Building) |

| Designated | May 6, 1973[1] |

| Reference no. | 73000317 |

| Designated entity | McKim Building |

| Designated | February 24, 1986[1] |

| Reference no. | 73000317 |

| Designated entity | McKim Building |

| Designated | August 14, 1973[1] |

| Part of | Back Bay Historic District |

| Reference no. | 73001948 |

The Central Library (also the Copley Square Library) is the main branch of the Boston Public Library (BPL), occupying a full city block on Copley Square in the Back Bay neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, United States. It consists of the McKim Building, designed by Charles Follen McKim, and the Johnson Building, designed by Philip Johnson. The McKim Building, which includes the library's research collection, is designed in the Renaissance Revival and Beaux-Arts styles. The Johnson Building has the circulating and rare-books collections and is designed in the Brutalist style. Both sections of the Central Library are designated as Boston city landmarks, and the McKim Building is also a National Historic Landmark.

The Massachusetts state legislature set aside land in Back Bay for a central library in 1880, after the BPL's previous main library became overcrowded. Following several attempts to devise plans, including an unsuccessful architectural design competition, McKim was hired to design the modern McKim Building in 1887. Work began the next year, but construction was delayed partly due to cost overruns. Even after the McKim Building opened in February 1895, it took two decades for the building's artwork to be completed. To accommodate the collection's growth, the building was renovated in 1898 and expanded in 1918. Further growth in the collection prompted the BPL to consider expanding the Central Library in the mid-20th century, and the Johnson Building was thus developed from 1969 to 1972. The McKim Building was renovated in the 1990s, followed by the Johnson Building in the 2010s.

The McKim Building has a square floor plan surrounding an outdoor courtyard. Its three-story granite facade has a horizontal arcade and decorations such as medallions, with a main entrance facing east toward Dartmouth Street. Inside are several elaborately-decorated spaces, including a grand lobby and staircase, a second-story reading room called Bates Hall, and an elaborate third-floor lobby called Sargent Hall. The McKim Building is connected to the Johnson Building, which also has a square floor plan and a granite facade. The Johnson Building's facade has slanting lunette windows and a windowless upper section, and its interior is divided into square modules surrounding a central atrium. Over the years, the McKim Building's design has been praised, while the Johnson Building's design has received mixed commentary.

Site

[edit]The Boston Central Library is on Copley Square in the Back Bay neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, United States.[2] It occupies a full city block bounded by Boylston Street to the north, Dartmouth Street to the east, Blagden Street (originally St. James Avenue[3][4]) to the south, and Exeter Street to the west.[5] The original library, designed by Charles Follen McKim, is on the eastern half of the block. The western half is occupied by an annex designed by Philip Johnson.[6] The two sections of the building are about 2.5 inches (64 mm) apart.[7]

The library building overlooks the Boston Common park to the northeast,[8] as well as Old South Church to the northwest.[5][9] At the time of the library's development in the late 19th century, there were various brownstone houses to the north as well.[10] The library also faces Trinity Church,[2][10] which is across Dartmouth Street to the east.[11] Also across Dartmouth Street is a plaque to the Lebanese-born poet and philosopher Gibran Khalil Gibran, dedicated in 1977.[12] The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is across Copley Square to the south.[13] In addition, there is an ornamental portal to the MBTA subway's Copley station in front of the library's Boylston Street entrance.[14]

Development

[edit]

The Boston Public Library (BPL) was established in 1852,[15][16] and its first location, the two-room Adams Schoolhouse on Mason Street, opened in 1854.[15][17] Within three years, the collection occupied three buildings.[18] The original structure was replaced in 1858 by a new central library at 55 Boylston Street, which cost $364,000 to build[I] and originally had 70,000 volumes.[20][21] The second building's collection was split between a circulating collection, in a lower hall, and a research collection, in a upper hall known as Bates Hall.[21][22] The BPL's collection gradually increased with various donations,[23][24][25] and it had also outgrown the second building within ten years.[24][26] As such, the library system was granted permission to open branches in 1869.[24][27] The central library at Boylston Street had an annual circulation of 380,000 by 1872,[28] and the overcrowded collection posed a fire hazard by the late 1870s.[22] The central library had more than 250,000 volumes by the early 1880s, a figure that was growing by the year.[29]

Land acquisition and early plans

[edit]After the BPL was incorporated in 1878,[30] it requested that the General Court, the state legislature of Massachusetts, set aside a site in Back Bay for a new library.[23][28][31] The General Court gave the BPL a site on April 22, 1880, under the condition that construction begin within three years.[4][28][32] The site, at the corner of Boylston and Dartmouth streets,[4][28] covered about 33,000 square feet (3,100 m2).[32] The land was near Trinity Church and the Museum of Fine Arts,[23][25][28] and the Harvard Medical School owned a lot immediately to the west, extending to Exeter Street.[4][33] Henry Van Brunt and the city government's architect George Albert Clough separately drew up plans for moving the library to the English High and Latin School,[29][34][35] but the BPL's trustees determined these proposals to be impractical.[23][35] Clough next drew up plans for a new building on Dartmouth Street,[36][37] which were submitted to the Board of Aldermen, the upper chamber of the Boston City Council, in February 1883.[38] The city had not yet obtained the site at Boylston and Dartmouth streets due to uncertainty over where to move the library.[39][40]

In March 1883, the Board of Aldermen authorized $180,000 for land acquisition and $450,000 for the new building;[41][42][II] at the time, the BPL's trustees anticipated that only the research collection would go to Copley Square.[36][42] Shortly afterward, the state government gave the BPL three more years to begin construction,[3][37][36] and additional land was acquired south of the original plot.[3] An architectural design competition commenced in January 1884,[43][44] and the City Council set aside $10,000 in prize money, to be divided four ways.[44][45][44] Although the winning plans were supposed to have been selected in June 1884,[36][43] there was a delay in advertising the contest,[44] and there were disagreements over who should select the winning designs.[46][45] Ultimately, either 20[3][44] or 23 designs were submitted.[47] Charles B. Atwood won the first-prize award,[25][48] but none of the designs were ultimately selected, not even those that had won prizes.[44][36][49] The city government's architect Arthur H. Vinal said only four plans had even met the basic criteria;[a][47] all the other plans had been discarded without further review.[50]

In the absence of a suitable plan, Vinal was appointed to draw up plans,[36][51][52] but the design was delayed due to disagreements over the stacks and funding.[50] After the stacks debate was resolved, the BPL's trustees accepted Vinal's preliminary plans in October 1885.[53] Additionally, in order for the BPL to continue holding the land, construction had to begin by April 21, 1886.[3][36][54] Since the plans had not yet been completed,[51][54] workers began constructing foundations at 4:18 p.m. on that date, just before the deadline.[55] The plans, completed later that year, called for a three-story Romanesque Revival building.[52][56] Some of the foundations were completed and covered over in late 1886,[57] after $73,600 had been spent.[55][III] The BPL trustees no longer wanted to proceed with Vinal's plans by the next year;[55][58] the plans no longer met the trustees' requirements, but no one had full control of the project.[59] Additionally, no one was particularly impressed with Vinal's design.[55]

McKim design

[edit]On March 10, 1887, the BPL's trustees were given full authority to select their own architect.[36][55][60] The board of trustees' president Samuel A. B. Abbott went to New York to meet with Charles Follen McKim, a relative who headed the prominent architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White.[2][61] Following a series of negotiations,[61][62] McKim was hired to design the library on March 30,[62][63][64] to the consternation of local architects.[60] The trustees gave McKim free rein to draw up the plans,[65] which were tentatively planned to include a reading room, special-collection rooms, and space for 700,000 volumes.[10] McKim temporarily relocated to a Boston townhouse owned by his late wife Julia Appleton.[3][66] McKim wanted to design a structure that did not clash with Copley Square's existing architecture,[67] and he invited the architects Charles Howard Walker, Joseph Morrill Wells, and Sidney V. Stratton to help.[68] He considered modeling the building on the Villa Farnese, the Louvre Palace, or the Beaux-Arts de Paris before deciding on a design inspired by Paris's Sainte-Geneviève Library.[13][69]

The basic plans for the library were completed by mid-1887.[13] That October, the Board of Aldermen unsuccessfully attempted to divert $75,000[IV] allocated for the library to sewage pipes;[70] the plans were nearly complete by then.[71] The BPL approved preliminary plans on November 3, 1887,[13] and McKim continued to refine the design over the following months.[72] McKim considered going to Paris to ask his friend Honoré Daumet for inspiration, but McKim's partner William Rutherford Mead advised against it, telling him that "nobody but yourself can take care of the Library for the next three months".[68][72] Instead, McKim had a young draftsman, William T. Partridge, assist him in refining the design.[72][73] After the plans were finished, McKim presented it to the trustees,[74] who approved McKim's revised plans on March 30, 1888.[63][75] One trustee opposed to the plans, William Henry Whitmore,[76][77] later resigned in protest.[74][78] The approved plans were displayed in the State House,[63][75] and the BPL's trustees issued reproductions of McKim's drawings.[69]

When McKim's plans were approved, the trustees had around $350–360 thousand available.[b] The plans called for a Milford granite structure with a central court, a marble hall and staircase, space for various departments, and a 50-foot-tall (15 m) reading room on the second floor.[83][84] The building was intended to host a million volumes; at the time, BPL officials did not conceive that the collection would ever reach that size.[85] That May, the trustees were authorized to begin awarding contracts, at which point the building was to cost around $1.166 million.[81][63][86][V] excluding sculpture costs.[80] The City Council approved another $800,000 to cover the cost overruns.[88][89] The BPL requested bids for the foundation that July,[90] awarding the contract to Woodbury & Leighton.[91][92]

Construction

[edit]Exterior work

[edit]

A cornerstone-laying ceremony for the new library was hosted on November 28, 1888,[63][91][93] after a two-month postponement.[94][c] Shortly afterward, McKim closed his Boston office and moved back to New York.[74] The state legislature passed a bill in March 1889, allowing the city to borrow $1 million for the library.[VI][78][96] Meanwhile, the plans were changed slightly, and 70 stonecutters were working on the building by April;[97] some of the stonework had reached the top of the ground story by that May.[98] Several firms submitted bids for the general construction contract,[99] which was awarded to Woodbury & Leighton.[100] Contracts were awarded for other aspects of construction over the next two years,[100] and by the end of 1889, the foundations had been completed.[63] The stonework on the Dartmouth Street facade had reached the cornice by mid-1890,[101] and a worker was killed that October after falling from an arch.[102] Workers created a test section of cornice so McKim could examine its details,[103] and Abbott and McKim traveled to Europe to scrutinize the marble used in the building.[104]

The cost of the building (excluding furniture) had increased to $2.22 million by 1890,[VII][105] and the Massachusetts legislature authorized another $1.1 million for the project the next year.[VIII][63][106] Afterward, local newspapers published negative stories about the quality of the construction materials[107][108] and questioned whether the building had sufficient facilities for patrons.[109] The media also criticized the BPL trustees' plans to merge the research and circulating libraries in the new building.[107][108] Work on the roof was proceeding slowly by late 1891, at which point construction was planned to take at least three more years.[110] Little progress had been made on the interior,[110] and only the iron frame of the main reading room, Bates Hall, had been completed.[111] The entrance vestibule's ceiling had also sustained water damage earlier in the year.[112] By early 1892, the roof was being built, and the interior was being fitted out.[109]

Delays and completion

[edit]

Meanwhile, Mayor Nathan Matthews Jr. had delayed the $1.1 million loan while investigating the construction expenses,[113][100] thereby stalling construction progress.[113][114] An inscription on the facade, bearing the names of various historical figures, was removed after a controversy over the fact that the names formed an acrostic spelling out "McKim, Mead, White".[115][116] That July, the BPL's trustees notified Matthews that the work had already been delayed by five months.[117] Though some sources cite Matthews as having recommended that the BPL eliminate over $200,000 worth of expenses by eliminating artwork,[117][118] Matthews claimed that he had recommended saving only $50,000.[119] Matthews said that, after all expenses had been paid off, there would be $114,000 remaining for furniture.[100][120] The BPL's trustees were ready to award final construction contracts by late 1892,[117][118] and Matthews also dropped his opposition to the building's artwork.[117] From that point, construction proceeded without further delay.[121]

The artists Augustus Saint-Gaudens, John Singer Sargent, and Edwin Austin Abbey were hired in late 1892 to create art for the building,[122] and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes was hired to design mural panels the next year.[122][123] Because the trustees lacked money for some of the artwork, they accepted various donations.[122][124] For instance, a donation from the Weld family funded a sculpture by Frederick MacMonnies,[122][125] while another donation from Arthur Astor Carey financed murals by Joseph Lindon Smith.[122][126] The trustees also accepted William Todd's $2,000-a-year donation for a newspaper room in mid-1893,[127][128] at which point the first floor was finished.[129] The stacks and some upper-story rooms were being completed by that September.[130] Although the final layout conformed mostly to McKim's original plans, some of the rooms were reconfigured during construction, and the stacks were downsized.[131]

City officials were invited to tour the building in December 1893,[132] and a hundred workers were finishing off the interiors by then.[133] Further contracts for art were awarded in 1894 to James McNeill Whistler and Daniel Chester French,[122] though Whistler's contract was later rescinded.[134] One of the facade decorations, a seal designed by Kenyon Cox and sculpted by Saint-Gaudens, provoked objections because it depicted nude boys,[135] though these decorations were kept.[121] The collection of former BPL librarian Mellen Chamberlain was installed in the new library in early 1894,[136] and the BPL began moving its collection from the old building that September.[137] The new Central Library was originally supposed to open the same month,[138] but the entire collection was not transferred to Copley Square until January 27, 1895.[121] The old library, which had closed three days earlier,[121][139] was replaced with the Colonial Theatre and Building in 1900.[140]

Usage

[edit]Opening

[edit]

Officials were invited to tour the Central Library on January 31, 1895,[141] and it briefly opened during the first week of February.[142][143] After several delays,[144] patrons were allowed to begin borrowing books on March 11.[145][146] The architects held an informal reception in April 1895 to celebrate the completion of several paintings,[147][148] and the newspaper room opened the next month.[128][149] The Central Library was cited as the world's most expensive library,[139] with a cost of over $2 million.[d][IX] The building originally had a staff of 101 employees,[8] a capacity of 900 patrons, and around 6,000 volumes in Bates Hall and 91,000 in the specialized libraries.[145][142] Shortly after the building opened, there were complaints about the inefficient heating system and slow elevators,[153] and patrons reported issues retrieving books from the stacks.[148][154] The incomplete building also lacked a freight elevator,[155] and many of the artworks were not completed for several years, if at all.[134][156]

In the Central Library's first three years, BPL chief librarian Herbert Putnam made several adjustments.[145] The first pieces of de Chavannes's mural were installed in October 1895,[157] though the mural was not completed for two years.[158] A controversy arose in 1896 over a nude statue of Bacchante that McKim wanted to donate;[159] the statue was ultimately never installed.[160][161] Meanwhile, Bates Hall had become overcrowded within a year of opening,[161] and the BPL's trustees wrote to the state legislature in April 1898, requesting funding for modification.[162] The appropriation was approved that June[163] and was used to enlarge several departments, upgrade the stacks and mechanical systems, and add new offices.[164][165] By 1899, the Central Library had 550,000 volumes, three-fourths of the BPL's total collection.[166]

1900s and 1910s

[edit]It took more than two decades to complete the decorations.[167] John Elliott's ceiling mural in the children's room was completed in 1901.[168] The next year, Abbey's final murals were finished,[152][169] and the patent and statistical departments were expanded with the relocation of the binding and printing departments.[170] Another painting by Sargent was installed on the third floor in February 1903,[171] and Daniel Chester French was hired to design bronze entrance doors,[172] which were dedicated in November 1904.[173] Saint-Gaudens continued to work on the sculptures at the Central Library's main entrance, which were not finished when he died in 1907.[152][174][175] Bela Pratt, a student of Saint-Gaudens,[175] was hired in 1910 to complete the sculptures.[152][176] After a dispute over whether the city's Municipal Art Commission needed to approve Pratt's contract,[177][178] the commission accepted the proposal in 1911,[179] and the sculptures were installed the next year.[180] The BPL then closed out its new-building fund, setting aside some funds for Sargent's remaining murals,[152] which were installed in 1916.[181]

By the mid-1910s, the Central Library employed 142 staff.[182] The building had become a sanctuary for patrons such as the writer Mary Antin,[152] and students frequently used the third-floor libraries.[183] The artworks attracted visitors as well.[139] The building had more than 800,000 volumes,[184][182] and its card catalog had 1.6 million cards.[185] Due to a lack of storage space, additional shelves had been installed haphazardly throughout the building.[186][187] As such, Mayor James Michael Curley requested in late 1915 that the Boston City Council lend money to buy three adjacent sites on Blagden Street,[187] and the city bought the three sites that December for $122,500.[X][188] George B. Long was hired to build the annex in April 1916,[189] and work began the following month.[186] The new annex, designed by Joseph McGinnis,[190][191] was completed in 1918.[191][192] It included additional space for several departments and stacks,[192][193] as well as a distribution center for the branch libraries.[190] Former BPL trustee Josiah H. Benton, who had died the previous year, had bequeathed $2 million, which could be used to expand the Central Library or build a new main branch.[e][194][195]

1920s to 1940s

[edit]

Even after the Central Library had been expanded, the BPL found it hard to adapt the existing building to its needs.[196] In 1920, the BPL added a three-room information bureau on the ground floor;[197] one of these rooms was within a former restroom.[196] There were attempts to remove Sargent's controversial Synagogue mural in 1922,[198] but the mural was not removed.[199] A World War I memorial tablet was dedicated in the courtyard in 1924.[200] By mid-decade, parts of the building were overcrowded,[201][202] and the trustees suggested erecting a new building or expanding the Blagden Street annex.[203] Additionally, the mechanical and book-delivery systems had broken down,[201] and many books were being stolen.[204] As such, the trustees recommended in 1925 that $50,000 be set aside for repairs.[XI][201][205] The mechanical and book-delivery systems were rebuilt during the mid-1920s.[206][207] The lights, roofs, marble floors, and lecture hall were also renovated, and a sprinkler system was installed.[207]

In 1927, the BPL agreed to move the Central Library's business collection to the Harvard Business School.[208][209] The same year, the City Council allocated funds for repairs, which ultimately cost $450,000.[XII][206] Workers replaced flammable wooden decorations with fireproof metal,[145] and they repaired the building's foundations, which had been weakened significantly due to a lowered water table.[210] The business branch opened in 1930,[209][211] and work on the foundations continued through the next year.[210] In the mid-1930s, the BPL set aside $987,000 for a new classification system.[XIII][212] Meanwhile, due to legal disputes, the BPL did not receive any money from Benton's bequest until 1936; the Benton fund and another 1938 bequest were used to acquire books.[213] By 1939, the roof was leaking,[214] and a City Council member had requested money to clean the facade, which had become dirty.[215]

The de Chavannes and Sargent murals were restored in 1940,[216] and a room for Albert H. Wiggin's art collection opened on the third floor in June 1941.[217][218] The tiled roof was replaced with tarpaper in 1942,[219][220] and nearly 100,000 volumes were relocated from the building to the New England Deposit Library that year.[221] A war information center opened in October 1942[222] and was expanded the following year.[223] In 1947, the merchant John Deferrari bequeathed the BPL $3 million, part of which was reserved for an expansion of the Central Library;[f][224][225] he later gave another $500,000.[226] In exchange, the BPL commissioned a portrait of Deferrari to be displayed in the building.[225][227] The next year, the BPL paid Boston University $500,000 for four adjacent buildings, extending to the western end of the block;[228] the university was allowed to remain until 1959.[229][230] By the late 1940s, half of the Central Library's patrons lived outside Boston,[231] the interior courtyard was a popular meeting spot,[232] and the building hosted regular art exhibitions.[233] The design was functionally obsolete due to overcrowding and the inconvenience of retrieving books from the stacks.[234]

1950s to 1970s

[edit]

The socialite Sylvia Wilks bequeathed about $600,000 to the BPL in 1951.[XIV][235] The open-stack and audiovisual departments opened in the Central Library in January 1952,[236][237] and a children's room opened that November.[238] Under chief librarian Milton Lord, the BPL announced in late 1953 that it would raise $1.5 million for an expansion of the Central Library, with another $2.5 million coming from previous bequests.[XV][239] During that decade, the courtyard was renovated,[240] the cellar was refurbished,[241] and the building's administrative offices were consolidated in the old stacks.[229] In addition, since the roof was in danger of collapsing,[220] a contractor was hired in 1956 to install roof tiles.[219] The BPL had encountered difficulties raising money for the Central Library's expansion from the public,[242] but it nonetheless announced plans in 1957 to study the expansion.[230][243] At that point, the Central Library had 2.1 million volumes,[230] and some books had to be stored on Long Island in Boston Harbor.[7]

By the early 1960s, the Central Library was popular among students because of its large collection, central location, and Sunday operations.[244] The BPL's trustees appointed an advisory panel in mid-1963 to select an architect for the expansion,[245] and they selected the modernist architect Philip Johnson that October.[246] The BPL's trustees planned to demolish the Blagden Street annex and convert the original building to a research library.[247] Johnson detailed his plans for the annex in 1967; by then, the building was to cost $23 million, with the city government providing $18 million.[XVI][248] Johnson's original design included no windows,[249][250] but he subsequently added glass expanses to the roof and facade.[251] Work had still not commenced by late 1968,[252] and a construction contract was eventually awarded in April 1969 to Vappi & Company.[253] The granite quarry that had supplied material for the original library was reopened to provide stone for the annex.[254] The annex's roof and top story were constructed before the third through sixth stories, which were suspended from the top story.[255]

The original library's facade was cleaned in 1971.[256] The Johnson Building was dedicated on December 11, 1972,[254][257] having cost around $23 million.[XVII][6] The Johnson Building housed the stacks and circulating collection, while the older building (which became the McKim Building) became a museum and research library.[7] Three million volumes were moved to Johnson's annex,[6][257] while other books were stored elsewhere.[7] Although the BPL had wanted to re-landscape the block, it was unable to do so because of persistent funding shortages.[258] These funding shortages also prompted the Central Library to discontinue all Sunday service for the first time ever in 1977.[259] No dedicated endowment existed for the Central Library, so it had to share funding sources with the BPL's branch libraries.[260] By the late 1970s, the Central Library had a debate club, a children's film festival, various activities for youth, and a lecture program.[261]

1980s and 1990s

[edit]The BPL commissioned reports on a potential renovation of the McKim Building in 1981.[262] The BPL had so little money, it was considering closing its branches just to keep the Central Library open;[260][263] it ultimately opted to close the Central Library on Saturdays.[264] At that point, three-fourths of patrons were students.[265] Saturday service ended in December 1981,[266] and the Central Library lacked weekend service until it reopened on Sundays in 1983.[267] An education information center opened there in 1984,[268] and the BPL hired consultants the same year to advise on the restoration of the McKim Building.[269] In August 1985, the Boston government announced that it would allocate $13.4 million for renovations,[269][270] and Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson and Abbott was hired to design the renovation.[262][270] The McKim Building had leaks, a malfunctioning heating system, inadequate lighting, outdated wiring, and damaged artwork.[262] Parts of the interior were unused,[271] while other spaces were used for storage or were not readily accessible.[272] Despite these issues, the McKim and Johnson buildings each had a million annual visitors.[7]

The BPL started raising $49 million for system-wide upgrades in 1986.[273][274] This was to include $16 million for the McKim Building,[274] whose renovation was slated to cost $28.4 million.[275] Multiple groups were organized to raise funds,[276] but work did not begin until 1991.[277] The project included constructing a new stair to the basement; renovating some unused rooms; and upgrading mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems.[277] In addition, several artworks were restored, including de Chavannes's murals and Saint-Gaudens's lions in the staircase hall.[278] The building remained open throughout the project.[279] In 1992, the Boston Public Library Foundation was established to raise money for the McKim renovation and BPL's other projects;[272] it raised $10.5 million in two years.[280] The first phase of the renovation (covering the facade, artwork, and main entrance) was completed in May 1994,[281][282] and seven-day service resumed the same year.[283]

A second phase of renovations, costing $19.7 million, commenced in October 1996.[284] This work included restoring Bates Hall, several other interior spaces, and the courtyard.[285] Bates Hall was closed so its floor, windows, ceiling, and mechanical systems could be refurbished.[286] After Bates Hall reopened in November 1997,[286] the other interior spaces were restored.[287] A corridor to the Johnson Building was also built.[285][288] The basement was flooded in August 1998,[289][290] causing $18 million in damage.[291] The flood inundated 3.5 million items, of which two-thirds were saved,[291] and two of the Central Library's departments were temporarily relocated.[290] In 1999, the City Council paid the $10 million insurance deductible for the flood damage,[292] and the Massachusetts government allocated $15 million to pay for continued renovations and replace destroyed items.[279][293] By then, the renovation was expected to cost $60 million, and the Johnson Building also needed repairs.[279]

2000s to present

[edit]

By the early 21st century, the Central Library was frequented by vagrants[294] and had also become a popular place for weddings.[295] A $7 million renovation of the courtyard was completed in 2000.[296] The BPL commissioned a replica of McKim's Bacchante statue,[279][297] which was installed in the courtyard.[298] Sunday service at the Central Library was temporarily discontinued between April and September 2003 due to funding shortfalls.[299] The same year, Harvard Art Museums' Straus Center for Conservation started restoring the Sargent murals,[300] completing the project in 2004.[301] Norman B. Leventhal also donated $7.1 million in 2004 to establish the Central Library's Leventhal Map Center.[302] The BPL established the Hub Computer Center on the McKim Building's second floor in 2007.[303] Catered Affair was hired to operate two restaurants at the Central Library in 2009,[304][305] and it renovated the map room and courtyard.[305] When the Kirstein Business Library was closed that year,[306] its collection was moved to the Central Library's basement.[307] The BPL started converting one room of the McKim Building into the Leventhal Map Center in January 2011,[308] and the center opened that October.[309]

The BPL began planning the Johnson Building's renovation in 2012.[310] Mayor Thomas Menino pledged to begin the Johnson Building's renovation before he left office in 2013,[311] and the City Council set aside $16 million for renovations.[312] William Rawn Associates was hired to design the renovation,[310][312] which included adding retail and refurbishing the interiors.[310][313] The first phase, consisting of a new children's library, was finished in February 2015.[314][315] That November, the BPL's board of trustees approved a cafe and radio studio in the Johnson Building.[316] The second phase, which included refurbishing the basement, first floor, and mezzanine,[317] was completed in July 2016.[318][319] Because the entire Central Library was a city landmark, the Boston Landmarks Commission had to approve the design changes.[319] The project cost $78 million in total.[320][321] One of Puvis de Chavannes's murals in the McKim Building was also restored[322] and was reinstalled in September 2016.[323][324] By then, the Central Library had 3.6 million annual visitors.[325]

Mayor Marty Walsh planned to spend another $128 million upgrading the BPL and renovating the Central Library by 2019.[326] At the time, the McKim Building's 1990s renovation was still incomplete, and fundraising had stalled.[326][327] The Fund for the Boston Public Library was established in May 2019 to raise money for several BPL projects, including the McKim Building project.[326][328] The same year, the Map Room restaurant was renovated.[304][329] The Central Library was temporarily closed in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, reopening for limited service that August[330] and full service in June 2021.[331] The BPL reopened the Central Library's special collections in September 2022 following a five-year renovation that cost $15.7 million.[332][333] The BPL began offering audio tours of the Central Library in late 2024,[334][335] and it started planning the McKim Building's renovation in 2025.[336]

McKim Building

[edit]

The original part of the Central Library, known as the McKim Building,[7] is a three-story Italianate Renaissance structure designed by Charles Follen McKim, measuring 70 feet (21 m) high from ground to cornice level.[337][338] The structure's floors are nearly square, measuring 225 feet (69 m) wide and either 227 feet (69 m)[337][338] or 229 feet (70 m) across, with a central interior courtyard.[339] The McKim Building houses the Central Library's research collection.[340] Several artists, including Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, John Singer Sargent, Daniel Chester French, and Edwin A. Abbey, were hired to decorate various parts of the building.[156][341][342] James McNeill Whistler and John La Farge were asked to design other art for the building but never did so.[341] The Christian Science Monitor wrote in 1915 that the art was the building's main feature.[343]

The design was largely inspired by Paris's Sainte-Geneviève Library, designed by Henri Labrouste.[13][191][103] The Boston Central Library's design has a horizontal arcade, contrasting with the vertical design elements of the nearby churches,[13][344] though the arcade is shorter than that at Sainte-Geneviève.[103] The design was also inspired by the San Francesco cathedral in Rimini, as well as the Marshall Field and Company Building in Chicago.[345][346] The selection of the Renaissance style was influenced by the fact that McKim, Mead & White's Villard Houses, which BPL trustee Samuel A. B. Abbott had visited while in New York, were designed in that style.[63]

Exterior

[edit]The building sits on a granite plinth slightly above Copley Square.[347][348] The plinth surrounds the building on three sides and is three steps above the sidewalk;[349][350] at Dartmouth Street, three additional steps rise to the entrance.[350] The facade is made of Milford granite[83][351] and is articulated with horizontal decorative features such as belt courses, friezes, windows, and cornices.[347] The granite is light-gray[348][352] and originally had colorful specks.[349][352] The lowest section of the facade is clad in large blocks of granite; the joints between the blocks are shallow, giving that section of the wall a flat appearance.[347] Above, the facade is arranged into two horizontal tiers: the first story, which is rusticated, and the second and third stories, which has wide arched windows that form arcades.[347][348][353] These tiers are separated by a belt course, the lower half of which has Greek key decorations;[347] the third story is within the upper tier.[354]

On all three elevations of the facade, there are dark Roman-styled grilles in front of each arched window on the second and third stories.[347] In the spandrels diagonally above each window are decorative stone medallions by Domingo Mora.[349][355] There are 33 such medallions,[355][356] representing early printmakers and booksellers,[356][357][g] though Mora had initially intended to use 50 medallions.[358] Above the third story, McKim carved monumental inscriptions in the entablature,[347][359][360][h] above which is a cornice with egg-and-dart motifs, dentils, and a cyma recta molding.[349][362] The building is topped by a low hipped roof made of Ludowici tiles,[363] which were originally tinted purple[352] and were made by Lindemann Terra-Cotta.[100] The roof is covered with a copper cresting depicting shells and dolphins,[349][364] and it originally had stamped-copper dragons at each corner.[133] There were also six skylights, a ventilator, and chimneys on the roof;[365] these were removed in the mid-20th century.[366]

Dartmouth Street

[edit]

The main elevation of the facade is on Dartmouth Street, which is 13 bays wide;[356] the bays are grouped into three sections, with an entrance in the central section.[347] The first story has ten windows, five on either side of a centrally-located main entrance.[349][347] A series of broad granite steps ascend to the main entrance, in the center of the facade.[353][362] These steps are flanked by pedestals, which support a pair of seated bronze female figures, carved by Bela Pratt.[180][367] The left-hand figure depicts science, while the right-hand figure depicts art.[368][369] Scientists' and artists' names are carved into the pedestals.[369][370] In front of the steps are granite bollards, some of which have reliefs depicting eagles.[356]

The main entrance consists of three archways leading to a vestibule.[353][362] Each of the archways is one bay wide and is surrounded by archivolts with elaborate moldings.[356] The keystone above the center archway has a carved head of the goddess Minerva,[353][369] created by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Mora.[367] The words "FREE TO ALL" are inscribed above the central keystone.[359][356] Within the archways are wrought-iron gates, interspersed between four ornate wrought-iron sconces.[349][352][367] The soffits or ceilings of each archway are decorated with rosettes.[369] On the second story of the Dartmouth Street elevation are 13 double-height arched windows,[348][356] which are arranged symmetrically.[25] The names of noted historical figures are inscribed beneath the outer ten windows.[353][356] The spaces below the three central windows contain official seals of Boston, the BPL, and Massachusetts,[367] sculpted by Saint-Gaudens.[371][349]

Other elevations

[edit]The Boylston Street elevation, to the north, is 11 bays wide[356][358] and is also grouped into three sections.[347] The center three bays contain a secondary entrance,[349][356] which served the periodical rooms.[372][373] Two of the arches originally led to a driveway, while the other led to a staircase.[97] The secondary entrance is less elaborately decorated than the main Dartmouth Street entrance, with wrought-iron gates, simple keystones, and wrought-iron chandeliers.[356] At the second story are double-height archways, but these are partially infilled with marble blocks, and there are smaller windows embedded in the marble infill.[358][374] As with the Dartmouth Street elevation, the bottoms of each archway contain carvings of historical figures' names.[358] The horizontal design elements on the Dartmouth Street elevation wrap around to Boylston Street as well.[374]

The Blagden Street (formerly St. James Avenue) elevation, to the south, has similar horizontal decorations to the Dartmouth and Boylston Street elevations, but is less ornately decorated and more utilitarian in nature. The western half of the Blagden Street elevation has few windows and no cornice, since the building's stacks were originally located there.[365] The easternmost two windows on the second story originally corresponded with Bates Hall, the library's reading room.[358] This elevation also had a smaller service entrance.[349] The former western elevation, abutting the Johnson Building, is made of utilitarian red brick.[365]

Interior

[edit]The ground (first) story is more utilitarian in nature, while the second story has the most ornate rooms, including the double-height Bates Hall. The third floor has various gallery and reading rooms leading off a central gallery space, Sargent Hall.[375] Due to the presence of Bates Hall, the third floor does not extend to the building's eastern end.[84] The building's cellar includes machinists' shops, storage areas, and the mechanical plant (which includes engines, fans, and pumps).[376][377][378] In addition, there was originally a ventilation-intake fan in the central courtyard,[376] and there were originally 14 lifts and 3,200 lights.[377][i] The building has numerous fire-suppression, features such as metal fire doors, fireproof bookcases, and sprinkler systems.[379] The foundation consists of 4,500 wooden pilings,[230] each with steel-and-concrete poles above them.[207]

The building's carpentry was constructed by Ira G. Hersey, while the furniture was by Mellish, Byfield & Co.[380] Bowker, Torrey & Co. oversaw most of the marblework,[381] except for the grand stairway, which was constructed by Robert C. Fisher.[382] Post & McCord were responsible for the ironwork, and various other contractors received contracts for mechanical systems and plasterwork.[100] The library has one of the first major applications of Rafael Guastavino's Catalan vaults—a type of low brickwork arch forming a vaulted ceiling—in the United States,[156][383] The building's Guastavino tiles are laid in a herringbone pattern[383] and are used in the stairs, floors, walls, and ceilings.[384][i]

The original stacks are in the southwestern corner of the building.[365][131] They span six levels,[337][365][385] each measuring 7 feet (2.1 m) high to allow easy access to each shelf.[386] The stacks are separated from the rest of the building by brick walls.[351] Books from the stacks are delivered to library patrons via lifts, pneumatic tubes, and miniature railways.[340][337][385] Patrons requested books by submitting call slips to the book-delivery room, where pneumatic tubes sent the slips to attendants in each stack.[340][385] Books were returned to the stacks the same way.[337] The use of stacks contrasted with older library buildings, where books were stored in alcoves.[386] Some of the stacks were converted into offices after the collection was moved to the Johnson Building;[340] pneumatic tubes are still used to retrieve books from the Johnson Building.[7]

First floor

[edit]

The first-floor rooms are built around the courtyard, which measures 100 by 135 feet (30 by 41 m) across.[83][84] The court is based on that of the Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome.[365][387] It has a central fountain and reflecting pool, surrounded on three sides by a loggia with a brick floor, Doric-styled Tuckahoe marble columns, and a plaster vaulted ceiling.[387][388] The eastern wall of the court abuts the first-floor staircase.[389][390] The courtyard's second- and third-story walls are clad in brick with stone trim and have windows.[387][389][390] A copy of Frederick William Macmonnies's statue Bacchante and Infant Faun stands in the center of the courtyard,[389] and there are also a bust, a sculpture, and two tablets memorializing BPL staff and patrons.[387]

Lobbies and stairs

[edit]The main entrance leads to a vestibule with pink Knoxville-marble walls and ceiling vaults, as well as a pink-marble floor with inlaid pieces of brown marble.[391] The north and south walls of the vestibule have circular niches.[391] Macmonnies's sculpture of Harry Vane,[125] a former governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, is located in the south niche.[343][391] On the western wall are three pairs of ornate bronze doors designed by French,[173][392] which are topped by arches with wreaths and leaves.[375] These doors were added in 1904 and have low-relief allegories depicting, from left to right: Music and Poetry, Knowledge and Wisdom, and Truth and Romance.[392][393]

The vestibule leads to the entrance lobby, a windowless space[393] designed in a Roman style.[394] The entrance lobby is divided into three aisles by large Iowa-sandstone piers; the center aisle has a vaulted mosaic ceiling, while the side aisles have domed ceilings.[392][393] The ceiling is decorated with trellis patterns,[395] and the names of six prominent Boston residents are engraved into the central vault.[395][396][397] The names of 24 more Boston residents are engraved into the pendentives of the side aisles' domes.[352][395] As built, the vestibule has a Georgia marble floor with a central seal surrounded by zodiac signs,[396][398] in addition to engravings of several names associated with the building's construction.[397][398]

A 20-foot-wide (6.1 m) grand stairway,[351] accessed by an archway, ascends west of the entrance lobby toward an intermediate landing.[387][399] The staircase's walls are made of yellow Siena marble with black veins, while the stair treads are made of ivory-gray marble.[400][401] The landing has rhombus and hexagonal Numidian-marble inlays, while the ceiling is coffered.[390][402] An oak doorway, flanked by two windows, leads to a balcony overlooking the courtyard;[390][403] three arched windows rise above these openings.[399] Short flights of stairs ascend to the north and south, turning east before continuing to the second floor.[403] These flights abut two marble lions, sculpted by Saint-Gaudens in memory of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia's 2nd and 20th regiments.[404][405] On the upper sections of the walls are ten mural panels by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes,[406] his only work outside France.[324] The panels are predominantly blue;[343][407] the largest panel depicts nine muses, while the others depict various academic disciplines such as history and poetry.[406][407]

Other first-floor spaces

[edit]

The rest of the first floor has rooms for several departments.[372][408] Two corridors lead west from the entrance lobby to the central courtyard, flanking the main stairway.[372][387][408] Each corridor has marble wainscoting and red-plaster walls. Various rooms lead off the corridors, and there are a coat room and bathroom below the stair.[372] At the first floor's southeast corner is the original catalog room, which has a terrazzo floor, brick wainscoting, Guastavino-tiled ceilings, and a mezzanine gallery. This abuts a book-ordering room decorated in a similar style, with a fireplace.[409][410]

At the northeast corner of the first floor is a periodical reading room, furnished in a similar style to the catalog room,[409][410] with shelves and a fireplace.[372][411] A mezzanine-level gallery leads to more shelves and some administrative offices.[372] Two additional periodical rooms extend to the west.[410] Immediately next to the periodical reading room, and decorated in a similar style, is the current-periodicals room.[372] Another, larger room farther west abuts the Boylston Street entrance and the courtyard.[410] The Boylston Street entrance originally led to a carriage driveway, which was enclosed in 1898, becoming a reference room.[164][372] This part of the building also had patent and scientific library rooms.[373] The first floor's northwest corner has various utilitarian rooms for the library's printing office.[408][409] These included a bindery and book-repair shop,[412] as well as a shipping room.[378]

Second floor

[edit]At the top of the grand stair is a north–south corridor on the second floor, which leads to three lobbies.[413] From north to south, the Venetian lobby links with the children's room; the Bates Hall lobby connects to Bates Hall; and the Pompeiian lobby links with the book-delivery room.[414] The corridor has Siena-marble wainscoting, an Istrian-marble floor with yellow-marble inlays, and a vaulted plaster ceiling.[413] Five archways overlook the stairs to the west,[401][415] and there is another stair at the hallway's northeastern corner and an elevator at the southeastern corner.[416] A staircase, with gray sandstone treads and green-marble railings,[417] continues east from this corridor, ascending to the third floor.[418]

Bates Hall

[edit]

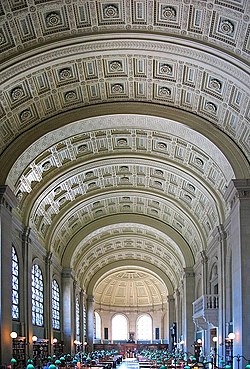

The second floor's main reading room, Bates Hall,[419][420] is named after one of the BPL's early benefactors, the financier Joshua Bates.[419][421] It measures 218 by 42.5 feet (66.4 by 13.0 m) across and 50 feet (15 m) high.[337][422] The room spans the entire Dartmouth Street elevation of the facade,[342][416] with semicircular apses at the north and south ends.[423] The space is decorated in a ivory and blue color scheme.[416][424] The terrazzo floor is surrounded by yellow marble, while the piers supporting the ribs are made of Ohio sandstone.[422] The plaster ceiling is a barrel vault,[352][416] which was originally colored cream and green.[352] There are transverse ribs at regular intervals; the ribs are decorated with Greek-key motifs, while the sections of ceilings between each rib have elaborate coffers.[416]

A colonnade with arches wraps around the east, south, and west walls, though the archways on the west walls are filled in with plaster.[416] At the center of the west wall is a doorway from the Bates Hall lobby, above which is a balcony,[424][425] accessed from the third-floor staircase.[417] There are two other large doors on the west wall, flanked by Corinthian-style, black-and-green-marble columns, which lead to the children's and delivery rooms. These three doors flank a pair of marble and sandstone fireplace mantels.[424][425] Near the tops of the walls is a frieze with the names of artists, scientists, authors, and philosophers.[352][425] The walls also contain English-oak bookcases on red-marble platforms, which are placed between the piers on each wall.[352][426] Bookcases separate the central section of the room from the apses at either end.[424][427] The southern wall of the room has wooden paneling and marble busts of literary figures and Boston residents.[380][427]

Bates Hall has various hickory armchairs and tables.[427] As built, Bates Hall had 33 tables[352][427] and could fit up to 300 patrons;[427] as of 2023[update], the room can seat 330 people.[428] Every spot at each table is assigned a number; library patrons could fill out "call slips" to request that books be delivered to the indicated seat number.[427] The workspaces are illuminated by 56 lamps on the tables,[335] in addition to wall sconces.[427] A card catalog was originally located at the south end of the room[337][427] but was moved to the children's room in 1975.[429]

Other second-floor spaces

[edit]The Pompeiian (south) lobby is a square room with a groin-vaulted ceiling, sandstone walls, and multicolored plaster decorations by Elmer E. Garnsey.[430][431] This lobby has elevator doors on its western side and a niche on its eastern side.[430] Next to it is the book-delivery room, which measures approximately 33 by 65 feet (10 by 20 m) across[j] and is decorated in the Early Renaissance style.[381] The floors are laid in a checkerboard pattern, with Verona red and Istrian gray marble,[432][433] and there is an oak desk.[434] The walls have a high oak wainscoting interspersed between marble pilasters.[435] Quest of the Holy Grail, a series of Pre-Raphaelite style murals by Abbey, decorates the tops of the delivery room's walls;[424][435] it depicts the search for the Holy Grail.[343][435][150] There are also three red-and-green-marble doorways to the corridor and Bates Hall,[432] as well as a fireplace mantel made of the same materials.[433] The ceiling has large wooden beams in the style of the library at Doge's Palace.[435]

Behind the delivery room is an alcove, where library attendants retrieved books using pneumatic tubes.[385][436] Staff members also used the pneumatic tubes to request books, sending patrons' call slips to workers in the stacks.[385][436] A simple librarian's office leads off the alcove and delivery room, facing Blagden Street;[436][437] it was described in 2018 as having an open layout, a green color scheme, and bookcases.[438] An elevator and stair lead from the librarian's office to the stacks,[378] and a staircase ascends to a mezzanine with an autograph-collection room.[437][439] Also on the mezzanine is the trustees' suite, with Empire style carvings, a limestone fireplace mantel, oak floors, and portraits.[436][439][126]

The Venetian (north) lobby is a square room with multicolored decorations by Joseph Lindon Smith.[126][440] It contains lunette panels depicting scenes from Venice, niches with the names of Venetian doges, and a domed cross vault.[440][441] Next to it is the children's (now catalog) room, which is the same size as the delivery room and has simpler decorations.[442][443] The floors are made of marble,[444] and the walls have a pink-marble dado, red-plaster surfaces, and a pink cornice. There is a fireplace on the eastern wall, and a gallery on the northern and western walls, accessed by two spiral staircases.[442][443] To the west is the second children's library (originally the patent room),[442][445] which has The Triumph of Time, a ceiling mural painted by John Elliott.[343][168][429] Past the patent room (from east to west) is a landing for a stairway that descends to the Boylston Street entrance, as well as several additional rooms.[446] Among these is the original newspaper room, a rectangular space with simple decorations;[429] it later became a new-periodical room.[444]

Third floor

[edit]Sargent Hall, named after the Triumph of Religion mural group that John Sargent painted there,[420][417] leads to the art room and several private libraries.[418] Sargent Hall's floor and wainscoting are made of sandstone. Four piers divide the western and eastern walls into three panels each, and which support a vaulted ceiling. The west wall has a door to the music library, and the north and south walls have additional doors to the other libraries.[444] The murals, painted between 1895 and 1919, are within the hall's walls, lunettes, and vaults;[447] they depict various religious-history scenes, including one panel called Synagogue.[150][447]

The rest of the third floor is devoted to the special libraries, which are lit by windows overlooking the courtyard.[448] From north to south, they are the Barton library, music library (now treasure room), and fine arts room (now Wiggin Gallery).[449] All three rooms have terrazzo floors and vaulted plaster ceilings.[450] The tables in each room are placed along the inner walls, while niches for special collections are placed on the outer walls.[450][451] The fine arts room and Barton library both have terrazzo floors. plaster walls, and domed ceilings with oculus windows.[450][452] Both rooms have iron galleries providing access to the upper portions of the shelves.[452] The music library has plaster walls, with a fireplace on its south wall.[448]

Johnson Building

[edit]The Johnson Building was designed by Philip Johnson in the Brutalist style[453][454] and opened in 1972.[321] William LeMessurier was the structural engineer, while Francis Associates was the mechanical engineer.[253] The Johnson Building houses the BPL's main circulating circulation and is the headquarters for the network's 24 branch libraries.[455] The structure measures about 230 by 230 feet (70 by 70 m) across.[257] In designing the building, Johnson used the same materials as the original McKim Building, making his annex no taller than the original structure.[234][453] Johnson also stated that he wanted patrons to experience "the shock of big space".[249]

Exterior

[edit]

Like the McKim Building, the Johnson Building is made of plain Milford granite[456][457] and is divided horizontally into three tiers.[457] Vertical piers separate each elevation into three bays.[257][457] The lowest tier of the facade has recessed windows. The center bay on Boylston Street has doors, above which is a granite entablature bearing the Boston Public Library's name.[457] Originally, the ground-floor windows were hidden behind 112 vertical granite slabs[458] and had dark, translucent windows on Boylston Street.[321][459] The slabs were mostly removed, and the windows replaced with taller transparent panels, during the 2010s.[460][459]

The middle tier has arched lunette windows, which slant outward;[255][457] the middle tier's facade is suspended from brackets and hangers on the upper tier.[255] Above a deep incision (which illuminates offices on the fourth floor) is the windowless upper tier,[257] which protrudes past the vertical piers.[457] The Johnson and McKim buildings' cornices are at the same level,[253][461] though the Johnson Building's roof slopes upward to a skylight.[255]

Interior

[edit]The interior is laid-out around a three-by-three grid of square modules. The center module has an atrium with skylights,[191][258] in a similar manner to the McKim Building's courtyard;[257] this atrium is formally named Deferrari Hall.[320] As built, the Johnson Building included 10 levels with a combined 480,000 square feet (45,000 m2);[254] two of these levels are below ground.[255] The structure was planned with seating for either 1,000[248] or 1,200 people.[255][258] The mezzanine level includes eight long, thin orthotropic decks,[255] while the second floor is a post-tensioned concrete slab.[258] The third through sixth stories are suspended from 16-foot-deep (4.9 m) trusses on the seventh floor.[255][258] Each truss is supported by steel posts that descend to the foundation 27 feet (8.2 m) below ground.[255] There are 36 steel posts, with 16 at the central atrium's corners and the rest along the building's perimeter; this allowed the spaces to be largely column-free.[258]

Originally, the McKim and Johnson buildings were connected on two levels,[258] but these connections were hard to navigate.[249] The Johnson Building was decorated in neutral colors,[453] and a granite lobby connected the atrium to Boylston Street, but this was removed in the 2010s.[320] As part of the 2010s renovation, a larger hall to the McKim Building was added,[318][321] and a mezzanine with several departments was built.[318] The ground floor of the Johnson Building has had a reception desk, new-book section, cafe, and studio for radio station WGBH.[321][454] These spaces are within a double-height space called Boylston Hall, with an undulating wooden ceiling.[454] In the basement is a 342-seat auditorium called Rabb Hall[462] and a business library.[318][319]

The second floor has a children's library with multicolored decorations, in addition to reading rooms for teenagers and adults.[314][460] The children's library, spanning two modules,[320] is divided into several sections, corresponding to collections for children of different ages.[460] The teenagers' reading room is decorated with old transit signage, a preserved street light, and a depiction of the Zakim Bridge, and there is an adjacent teen lounge.[460] The adults' reading room has a study area including tables with power outlets, a space overlooking Boylston Street, and red bookshelves for nonfiction collections.[320][460] Reading areas also surround the central atrium.[454] The Johnson Building's interior has a bust of Edgar Allan Poe.[463]

Collections

[edit]The McKim Building has the research, photographs–prints, and microtext–periodicals collections, in addition to the public-document library and special collections. The Johnson Building has the circulating and rare-books collections.[191] The BPL maintains a book-repair shop where these objects are repaired.[412][464] More than 200,000 items in the special collections are also viewable online as of 2022[update].[465]

An article from the 1990s quoted the Central Branch as having nearly 10 million patents, 6 million books, and 3 million government documents, in addition to hundreds of thousands of microfilm reels, prints, artworks, musical scores, and films.[466] The collection also includes rare books, children's books, postcards, magazines, and maps.[7] A 2007 article from the Boston Globe cited the BPL as having 1.7 million rare volumes, which were mostly housed at the Central Library.[464] As of 2022[update], the collection included copies of the United States Declaration of Independence, Robert McCloskey's drawings, William Shakespeare's First Folio, the The Liberator newspaper, and a Robert Aitken Bible (the first English-language Bible published in the U.S.).[333] Other items include a book belonging to 15th-century printer William Caxton,[467] numerous Rembrandt prints, 350 items about the artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 6,000 items from the 20th Massachusetts Regiment, 25,000 photographs from local newspapers, 25,000 color postcards, and 40,000 negatives by photographer Leslie Ronald Jones.[465]

When the McKim Building opened, its collections had Thomas Pennant Barton's collection of English literature; New England history volumes from Barton, Thomas Prince, and John A. Lewis; and George Ticknor's collection of Spanish literature.[468][469] The building included a collection of music volumes from Allen A. Brown,[448] the personal library of BPL librarian Mellen Chamberlain,[136][137] and the personal library of former U.S. president John Adams.[133][136] Also included were Nathaniel Bowditch's math and astronomy collections, Theodore Parker's theology and history collections, Antonio Tosti's engravings, and collections of items about Benjamin Franklin and the West Indies.[469] The special libraries had various other collections organized by subject.[450] In the mid-20th century, the BPL's acquisitions included Albert H. Wiggin's collections of prints and drawings,[217][218] the collection of the painter Charles Herbert Woodbury,[470][471] and works from Thomas W. Nason and Arthur W. Heintzelman.[471] The Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, established in 2004,[302] has 200,000 maps including 5,000 atlases.[308][472]

Impact

[edit]The historian Leland Roth wrote that McKim's design for the Boston Central Library—along with his partners' nearly-contemporary designs for the second Madison Square Garden in New York, the New York Life Building in Kansas City, and the Omaha National Bank Building in Omaha—marked the beginning of the firm's adoption of Renaissance Classicist styles.[23] The completion of the McKim Building helped the firm financially.[74] One writer described the Boston Central Library as being McKim's most famous Massachusetts design,[473] while another attributed the building as "the first great example of 'civic art'".[56] The National Park Service's designation report for the McKim Building cites it as "the first outstanding example of Renaissance Beaux-Arts academicism in America".[345] When the McKim Building was completed, a sketch of the building was exhibited at the Boston Architectural Club,[474] and Hugh Ferriss sketched the Dartmouth Street facade.[475]

Reception and awards

[edit]Contemporary

[edit]

When the original Central Library plans were first announced, the Boston Globe likened the design to that of the municipal morgue,[476] while other critics compared the plans to the Beacon Hill Reservoir and a Roman marketplace.[354] Conversely, the San Francisco Chronicle praised the building as "one of the most remarkable library buildings in the country",[351] and the Boston Evening Transcript called the building "dignified, restrained, pure and correct".[477] The Boston Herald struggled to criticize the facade's design, and the Boston Daily Advertiser predicted that the Roman-style facade would be "a saving grace" to Copley Square.[354] The building was controversial when it was constructed, with some reviewers assailing its design as a failure, and others claiming that it was the United States' best library building.[478] William F. Poole of the American Library Association criticized the layout as being more aesthetically pleasing than functional;[106][107] his comments were rebuked by the BPL's trustees.[479]

As the McKim Building neared completion, the Evening Transcript described the McKim Building as a paragon of McKim, Mead & White's "feelings and convictions in respect to their art", proclaiming it as one of the United States' prettiest buildings.[349] A writer for Outlook said it gave the impression "of compactness joined with severe elegance",[342] and The Golden Rule described it "a marvel of beauty combined with utility".[480] The American Architect conducted an opinion poll, finding that the Central Library was one of the nation's ten most beautiful buildings.[481] Other commentators described the building as a homage to both art and literature.[151][482] Conversely, a writer for The Critic said the building had been far too expensive, the book-delivery system was flawed, and the reading room was too small.[483]

When the Johnson Building was developed, a Boston Globe writer said the design "denies all reasonable relationships and the differences of access, internal use, sum orientation and the like" because the facades were identical.[484] Ada Louise Huxtable wrote that the Johnson Building was "a complicated structure of outwardly deceptive simplicity", saying it complemented the McKim Building well, despise its spartan design.[258] Another architectural critic, William Marlin, wrote that the Johnson Building's design inconspicuously matched the older building's architecture, while the newer annex's "so-called monumentality is kept inside".[257] By contrast, Eric Engstrom wrote for the Boston Globe that the newer annex was dull and joyless, despite its functionality,[485] and other critics likened it to a fortress or armory.[320][321][453]

Retrospective

[edit]In the 1920s, the Boston Daily Globe wrote that the original Central Library dominated Copley Square "with its simple, but majestic front".[486] In the middle of the century, The Guardian and the Christian Science Monitor wrote that the McKim Building was highly regarded because of its aesthetics, despite functional shortcomings,[230][487] and David McCord wrote that the McKim Building's "immortality seems assured".[488] The building was also characterized as "symbol of the resurgence of American classicism".[23] and as Back Bay's "crown jewel".[104] A Christian Science Monitor writer said in 1989 that the McKim lobby dated from a time "when scholarship meant the study of classical thought, as reflected in classical architecture".[489] In 2005, Globe writer Sam Allis described Bates Hall as one of Boston's "secular spots that are sacred".[490] The Toronto Star described the McKim Building in 2008 as lasting evidence of the "wealth and artistic tastes" of the city's upper class, the Boston Brahmin,[491] while another source in 2011 cited it as combining historical architecture and late-19th-century technology.[492]

A writer for the Financial Times characterized the Johnson Building in 2007 as "surely worth a peep for any visitor" and one of the city's few important modern-styled buildings.[493] By the 2010s, The Wall Street Journal had written that the Johnson Building had "neither aged well nor inspired much love".[310] During the Johnson Building's 2010s renovation, the critic Alexandra Lange wrote that the Johnson Building's original design "had weight and presence", complementing the colorful interior spaces,[320] while Globe writer Vivian Wang said the building was "freighted with history and illuminated with modernity".[319] Another Globe writer said in 2017 that the rebuilt Johnson Building had "thrown itself open to the city", contrasting with the original, foreboding design, and that the new design reflected the BPL's expanded function.[325]

Commentators have also written about the juxtaposition of the McKim and Johnson buildings. A writer for the Globe said in 1982 that the McKim Building had a sense of grandeur while Johnson's building resembled "a monumental barricade",[494] Architectural critic Robert Campbell regarded the Johnson and McKim buildings as being like "an elephant squiring a gazelle down Boylston Street",[495] and he later said the Central Library was flanked by "buildings that are so much more architecturally excited".[496] Tom Keane wrote in 2013 that the "massive and delicate" McKim Building and the "simplistic and gloomy" Johnson Building contrasted sharply,[497] while The New York Times said the next year that the "gray-granite behemoth" of the Johnson Building was not as welcoming as the McKim Building.[458]

Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson and Abbott received the Boston Society of Architects' Parker Medal in 2001 for its restoration of the McKim Building.[498] William Rawn Associates' 2010s renovation of the Johnson Building won seven architectural awards,[459][499] including the American Institute of Architects and American Library Association's Library Building Award.[499][500]

Landmark statuses

[edit]The McKim Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973,[501] and it was further designated a National Historic Landmark (NHL) in 1986 for its architectural and historical significance.[502] The Central Library received city landmark status from the Boston Landmarks Commission in 2000.[503] While the NHL designation excludes the newer Johnson Building,[420] the city designation includes the annex's facade,[454][458] as well as its atrium and lobby.[320]

See also

[edit]- List of National Historic Landmarks in Boston

- National Register of Historic Places listings in northern Boston, Massachusetts

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Explanatory notes

- ^ Charles B. Atwood, O'Grady & Zerrahn, Clarence S. Luce, and Horace Burr are cited as having submitted the best designs.[48]

- ^ Various sources cite figures of $350,000,[79] $358,000,[80][81] or approximately $360,000.[82] This is equivalent to about $9.869–9.869 million in 2023.[19]

- ^ The original date was to have been September 17.[95]

- ^ Its cost is variously cited as $2.25 million,[150] nearly $2.5 million,[151] $2.6 million,[25] or $2.722 million.[139] According to Whitehill 1956, p. 192, the building cost $2,558,559 in 1912; this cost included artwork completed after the official opening.[152]

- ^ Benton's bequest was initially $1 million (equivalent to $15.676 million in 2023), but interest was allowed to accrue until the bequest reached $2 million (equivalent to $31.351 million in 2023).

- ^ Deferrari's bequest was initially $1 million (equivalent to $10.716 million in 2023), but interest was allowed to accrue to $3 million (equivalent to $32.148 million in 2023). After the bequest reached $2 million (equivalent to $21.432 million in 2023), half or $1 million would be used for the expansion.

- ^ The names of these figures have not been recorded.[358]

- ^ The inscriptions are as follows:[347][360]

- On Blagden Street (to the south): "MDCCCLII • FOUNDED THROUGH THE MUNIFICENCE AND PUBLIC SPIRIT OF CITIZENS"

- On Dartmouth Street (to the east): "THE PUBLIC LIBRARY OF THE CITY OF BOSTON • BUILT BY THE PEOPLE AND DEDICATED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF LEARNING • A.D. MDCCCLXXXVIII"[361]

- On Boylston Street to the north: "THE COMMONWEALTH REQUIRES THE EDUCATION OF THE PEOPLE AS THE SAFEGUARD OF ORDER AND LIBERTY".

- ^ a b For further information on architectural details, refer to Boston Landmarks Commission 2000, Small 1895, and Wick 1977.

- ^ Various sources give a width of 64 ft (20 m)[432] or 66 ft (20 m).[352]

Inflation figures

- ^ About $9.979 million in 2023[19]

- ^ The land appropriation would be about $5.002, and the new-building appropriation about $12.505 million, in 2023.[19]

- ^ About $2.206 million in 2023[19]

- ^ About $2.304 million in 2023[19]

- ^ About $0 million in 2024[87]

- ^ About $30.721 million in 2023[19]

- ^ About $68.719 million in 2023[19]

- ^ About $33.709 million in 2023[19]

- ^ About $71.643–82.787 million in 2023[19]

- ^ Equivalent to $2.67 million in 2023[19]

- ^ Equivalent to $0.692 million in 2023[19]

- ^ Equivalent to $6.354 million in 2023[19]

- ^ Equivalent to $17.265 million in 2023[19]

- ^ Equivalent to $5.528 million in 2023[19]

- ^ The amount to be raised is equivalent to $13.646 million, while the total expansion cost is equivalent to $36.39 million, in 2023.[19]

- ^ The total cost estimate is equivalent to $160.423 million, of which the city share is $125.548 million, in 2023.[19]

- ^ Equivalent to $127.077 million in 2023[19]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 15, 2006.

- ^ a b c Broderick 2010, p. 267.

- ^ a b c d e f Roth 1983, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d Whitehill 1956, p. 133.

- ^ a b Boston Landmarks Commission 2000, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Arnold, Alison (December 3, 1972). "Back Bay's new addition". Boston Globe. p. B11. ISSN 0743-1791. ProQuest 503456272.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anderson, Peter (October 5, 1986). "The People's Palace; a New Chapter for the Boston Public Library". Boston Globe. p. 18. ISSN 0743-1791. ProQuest 294383270.

- ^ a b Donald, Dick (March 11, 1894). "Libraries in Two Cities". The Kansas City Times. pp. 9, 10. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Roth 1983, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b c Roth 1983, p. 118.

- ^ "Map Viewer". boston.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved July 3, 2025.

- ^ Boosahda, Elizabeth (January 1, 2010). Arab-American Faces and Voices: The Origins of an Immigrant Community. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-78313-3. Retrieved July 3, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Roth 1983, p. 119.

- ^ Moskowitz, Eric (September 17, 2010). "The remaking of a grand entrance". Boston Globe. pp. A1, A13. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved July 13, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Boston Landmarks Commission 2000, p. 35.

- ^ Whitehill 1956, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Whitehill 1956, p. 43.

- ^ Whitehill 1956, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Whitehill 1956, p. 55.

- ^ a b Boston Landmarks Commission 2000, p. 36.

- ^ a b "Imperilled". Boston Daily Globe. March 2, 1879. p. 4. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Roth 1983, p. 116.

- ^ a b c Boston Landmarks Commission 2000, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e Garnsey 1894, p. 1015.

- ^ Whitehill 1956, p. 77.

- ^ Whitehill 1956, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c d e Boston Landmarks Commission 2000, p. 38.

- ^ a b "City Government". Boston Evening Transcript. October 31, 1882. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Public Library". Boston Post. April 18, 1878. p. 3. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Whitehill 1956, p. 131.

- ^ a b "The General Court". Boston Post. April 23, 1880. p. 3. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com; "The General Court". Boston Evening Transcript. April 23, 1880. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Site for the New Medical School Building". The Harvard Register; an Illustrated Monthly. Vol. 1, no. 6. May 1880. p. 101. ProQuest 90554451.

- ^ "The Public Library". Boston Daily Globe. October 31, 1882. p. 2. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Whitehill 1956, pp. 135–136.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Boston Landmarks Commission 2000, p. 39.

- ^ a b Whitehill 1956, p. 134.

- ^ "Board of Aldermen". Boston Daily Globe. February 27, 1883. p. 2. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Public Library". Boston Daily Globe. March 2, 1883. p. 2. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Public Library". Boston Evening Transcript. March 1, 1883. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "City Government". Boston Evening Transcript. March 27, 1883. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com; "Board of Aldermen". Boston Daily Globe. March 27, 1883. p. 5. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Whitehill 1956, pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b "The New Public Library Building". Boston Evening Transcript. January 4, 1884. p. 1. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Whitehill 1956, p. 138.

- ^ a b "The New Public Library". Boston Evening Transcript. November 26, 1884. p. 4. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Public Library". Boston Daily Globe. September 7, 1884. p. 2. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Public Library". Boston Daily Globe. January 20, 1885. p. 2. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Roth 1983, p. 387.

- ^ "The Boston Public Library". Boston Evening Transcript. June 4, 1886. p. 8. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The New Public Library". Boston Daily Globe. September 20, 1885. p. 5. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Whitehill 1956, p. 139.

- ^ a b "Boston Public Library". Boston Evening Transcript. November 16, 1886. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Public Library". Boston Evening Transcript. October 15, 1885. p. 1. Retrieved July 3, 2025 – via newspapers.com.