D. LeRoy Dresser

D. LeRoy Dresser | |

|---|---|

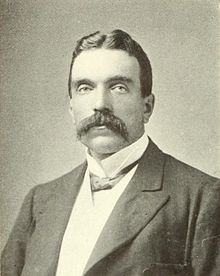

Photo of Dresser, by Fredricks, circa 1904 | |

| Born | Daniel LeRoy Dresser December 13, 1862 |

| Died | July 10, 1915 (aged 52) New York City, New York. US |

| Alma mater | Columbia College (1889) |

| Spouses | Emma L. Burnham (m. 1889; div. 1908)Marcia Walther Baldwin (m. 1914) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Edith S. Dresser (sister) |

Daniel LeRoy Dresser (December 13, 1862 – July 10, 1915) was an American merchant and banker.[1][2] He killed himself after he was bankrupted by the collapse of the United States Shipbuilding Company, a project that involved J.P. Morgan and Charles M. Schwab.[1][2] The New York Times wrote that his "rise and fall in finance was one of the greatest sensations of the banking history of the first decade of the century…."[1]

Early life[edit]

Dresser was born in Newport, Rhode Island to Elizabeth Stuyvesant LeRoy and George Warren Dresser, an Army brevet major.[3] His maternal grandparents were Susan Elizabeth (née Fish) and Daniel LeRoy.[1][4] His maternal great-grandparents were Elizabeth Stuyvesant and Nicholas Fish.[4]

His sisters included Edith Stuyvesant Dresser who married George Washington Vanderbilt II, and Natalie Bayard Dresser who married John Nicholas Brown.[2][5] His sister Pauline married Rev. George D. Merrill of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and his sister Susan married Vicomte Romain D'Osmoy of Normandy, France.[6][7]

In 1885, Dresser was a founding director of the Newport Fish and Game Association.[8] He attended of Columbia College, graduating in 1889.[9] There, he was a member of the Fraternity of Delta Psi (aka St. Anthony Hall).[9] He was also appointed to the committee of the Intercollegiate Athletic Club.[10]

Career[edit]

In 1889, Dresser started his first business.[1] He inherited a fortune, and became a member of Nelson, Goodrich & Dresser by 1891.[1] In 1894, the successful firm became Dresser & Goodrich.[1] By 1897, he was earning $100,000 a year.[1] In May 1897, he established Dresser & Co., a wholesale dry goods business that specialized in Japanese silks, hosiery, and webbing, with partners Charles E. Reiss and C. E. Sawyer.[1][11] Dresser & Co. "advanced money to manufacturers and sold silks on commission, and had representatives in Japan, China, and England."[11] The firm was located at 71 Franklin Street in New York City.[12]

Dresser's next business interest was the American Asiatic Steamship Company, and he served as its vice president.[1][11] He also became a director in the American Brass Company, the American Tubing and Webbing Company, and the Holmes, Booth & Hayden Company.[1] He was also president of the Richmond Realty Improvement Association.[13]

He was elected president of the Merchants' Association of New York in 1901.[14] Under his leadership, the group distributed a circular about the corruption of the New York City police department and of its leadership, saying it was "an injury to every interest in the city."[15] A newspaper had high hopes for their success, observing, "Men like Daniel LeRoy Dresser can not be threatened with moral blackmail which these many years have served to terrorize Tammany's enemies."[16] In January 1902, Dresser and the secretary of the Merchants' Association, met with President Theodore Roosevelt to discuss the need for a new post office in New York.[17] In April 1902, Dresser sent a letter to Roosevelt that mentions an investigation into silk frauds.[18]

In January 1902, Dresser became a founding director of the newly formed Trust Company of the Republic which was organized "to loan money to farmers throughout the country on warehouse receipts as security, and, when its resources will not permit of such loans, to become a headquarters for the negotiation of paper of that character."[19] The Trust Company had $1 million in capital and $500,000 in surpluses.[20] Dresser also served on the board of its associated Security Warehouse Company, which planned to build warehouses across the United States to store the cotton, rice, and raw materials received from the farmers.[19][1] On March 31, 1902, Dresser was president of the Trust Company which was located at 345 Broadway in New York City.[21][22][20] This banking business involved many prominent individuals in New York's financial world.[1] The New York Times noted, "He began to think and work in millions."[1]

In April 1902, Dresser was approached by John J. McCook from the law firm of Alexander & Green on behalf of John Willard Young, a son of Brigham Young, to support the United States Shipbuilding Company (USSC), an effort to merge seven large shipyards into one company.[23][24] As president of the Trust Company, Dresser authorized loans to form the USSC, with Young's promise that his company would earn $250,000 in bonds, $67,000 in cash, $700,000 in preference shares, and $700,000 in common shares.[23][20] Of the $9 million needed so that the USSC could issue bonds, the Trust Company underwrote $3 million, with the other necessary $6 million already secured by the Mercantile Trust Company on London.[22] In addition to being promoted by Dresser and Young, and USSC involved financier J. P. Morgan, Chicago lawyer and manufacturer Max Pam, steel magnet Charles M. Schwab, and naval architect Lewis Nixon who became its president.[1][25][26][23][12] If successful, the venture would have made millions for the USSC, millions for the Trust Company, and millions for Dresser.[1]

To fund the USSC loans, Dresser went to Wall Street, getting firms "to hold up prices on bonds that he underwrote, agreeing to take them at the market figures in addition to brokerage."[1] However, when the funding to issue bonds came due in August 1902, Dresser then learned that he had to raise another $1,750,000 because of delays in the London subscriptions; another $1,250,000 of the delayed London subscriptions were being raised in Paris.[22][27] Dresser contracted with John W. Young to sell $4,200,000 in USSC bonds in Paris in exchange for a commission of interim stock receipts that would be worth millions.[1] Young successfully arranged for the sale of these bonds, but the French investors were scared off when Morgan and Schwab sold their Bethlehem Steel Company to the USSC for $35 million in bonds, cash, and stocks.[1][22]

Dresser rushed to Paris to salvage the business deal and his companies which were heavily invested in USSC.[1] At this point, Dresser borrowed $3,500,000 under the Trust Company's name to support USSC—he was counting on the French investments in time for the loan's sixty-day note.[1] However, even Dresser could not rescue the Paris transaction.[1] In addition, he found Young in "state of collapse."[1] Furthermore, Young had drawn drafts in Dresser's name while in Europe, creating a hefty bill.[1] Back in New York City, Dresser found debt and obligations.[1] The Wall Street brokers started selling the USSC bonds instead of keeping them, forcing Dresser to buy them back.[1] Reportedly, the bonds came "in stacks and he took them as they came."[1] His Trust Company spent $250,000, as well as tens of thousands from other sources trying to maintain the value of the USSC bonds.[1] However, once rumors about the USSC circulated, its stock dropped from $350 a share to $50 a share.[1] At this point, Dresser personally owed banks $750,000; as the notes came due, he was not able to renew them.[1] Later, in 1909, Dresser testified that the Trust Company secured $4 million of the $6 million that the USSC had to pay on August 12, 1902.[27] Thus, when USSC failed, it also brought down the Trust Company.[27]

The crash of USSC also nearly caused a financial crisis for George Washington Vanderbilt.[28] Dresser had convinced his brother-in-law to purchase 100,000 shares of USSC at a time when Vanderbilt has spent most of his inheritance creating Biltmore Estate.[28] As a result of investing the estate's operating fund with Dresser, Vanderbilt had to scramble for cash, cutting the 120,000 acre Biltmore's operating budget from $250,000 a year to $70,000.[28]

On March 3, 1903, Dresser stepped down as president of the Trust Company of the Republic.[11] The firm's credit was so impaired that they suspended liabilities over $100,000.[3] However, Dresser paid off his debt of some $10,000 to the Trust Company before he resigned.[11] Dresser & Co. went into bankruptcy on March 7, 1903, also having been brought down by it investments in USSC.[11][29] Its assets were $750,000 and its liabilities were $1,250,000, with some forty creditors.[1][11] The collapse of the business ruined Dresser financially.[5] He testified in October 1903 that Morgan and Schwab cleared millions when they sold Bethlehem Steel to USSC, and they also sold their USSC stock worth $20 million ahead of all others.[22] In addition, Morgan and Schwab got their USSC bonds at 90% plus a bonus of 100%, while regular investors got their stock for 90% and a 25% bonus, and the public got their bonds at 97.5% wi$ no bonus.[22] In June 1902, the USSC claimed in a legal brief that certain promotors confederated to defraud the public by capitalizing the company at $41 million when it was worth $10 million and only had enough work for an income of $5 million.[30] Those accused of the scheme were USSC associates Charles J. Canda, Horace W. Ganse, Charles S. Hanscom, E. W. Hyde, John S. Hyde, Lewis Nixon, Henry T Scott, and Irving M. Scott, with Dresser from the Trust Company.[30] In this scenario, some participants were "dummies," including Young.[30]

Dresser paid more than $1 million of the $1.4 million in claims filed against him in 1903.[1] A newspaper report on April 9, 1903, indicated that some $850,000 had been given to Dresser by his friends to cover debts of Dresser & Co.; however, no funds came from his various wealthy relations.[31] He obtained a discharge from bankruptcy on March 5, 1907.[3]

Once on the road to financial solvency, Dresser sought "revenge on the men he thought responsible for his ruin four years before."[1] He filed eight suits against James Hazen Hyde, John Willard Young, the Mercantile Trust Company, the Commonwealth Trust Company (formerly the Trust Company of the Republic), members of the law firm of Alexander & Green, and others.[1][32] Dresser claimed that false representations totaling $15 million were made to him when he was asked to underwrite the USSC bonds.[1] In October 1908, due to lack of evidence, all of his suits settled out of court for around $200,000; Dresser still had to pay his legal fees from this sum.[1][32] Dresser left the courtroom "very angry" at this outcome.[32] Moving forward, he worked to reestablish Dresser & Co.[1]

On March 16, 1908, Dresser was arrested for the misappropriation of $4,000 related to the failure of the Trust Company of the Republic.[12] The charges against him were filed by William S. Andrews who was the former attorney for Young.[12] Andrews claimed Dresser failed to pay drafts issued to him by Young in 1903.[12] The case was dismissed because of the statute of limitations.[12] This was the only criminal case brought against Dresser in connection to the USSC and Trust Company failures.[12]

In September 1909, the courts ruled that the former directors of the Trust Company of the Republic were personally responsible for the debts resulting from Dresser's USSC loans because of their negligence.[33] The judge said the directors' claims that Dresser did not bring the loans to the board for approval did not remove them from responsibility as they would have learned of Dresser's reckless loans if they had been performing their duty as directors of the company.[33] Dresser always maintained that he did discuss the loans with the board, gaining their approval before seeking funding.[22][27]

On July 23, 1914, a western mining company named Dresser in a suit for $29,927 for a mortgage; however, the case did not come to trial.[1] On April 21, 1914, he was the defendant in another case filed by the Japanese firm Madawaya & Co. for promissory notes totaling $200,000.[21][1] In October 1914, he lost a court case of $200,000 to the Ichi Takayami Company of New York City.[2]

Near the end of his life, Dresser patented a steam generator that he claimed would save fuel.[1][2] However, he was unable to attract investors to bring it to market.[2][1]

Personal life[edit]

On November 20, 1889, Dresser married Emma Louise Burnham at St. Luke's Church in Matteawan, New York.[34] She was the daughter of Douglass Williams Burnham and the former Hannah Elizabeth Blodgett who lived at their home Beaconside in Matteawan.[35][34] The couple lived in Flushing, Long Island and also had a house at Oyster Bay.[34][3] Together, they had two children: Susan Fish Dresser (born 1890) and Daniel LeRoy Dresser Jr. (born 1894).[1][21] In October 1898, Dresser was hospitalized with a case of typhoid fever.[36]

Dresser was a member of the New York Yacht Club and the Seawanhawka-Corinthian Yacht Club.[1] He served on the graduate advisory committee of the Columbia University Athletic Association.[37] He also worked to clean up vice in Newport, Rhode Island.[2] In 1908 and 1913, he was the leader of the Progressive Party in Rhode Island.[21][1] However, in 1915, he and Dr. Oliver H. Huntington lost a case for $10,000 related to a Progressive Party celebration at Newport—although this loss was due to lack of ticket sales to see President Theodore Roosevelt rather than any wrongdoing.[2]

Dresser's business crisis in 1903 also lost most of his wife's money.[3][1] In 1908, he asked for police protection when death threats were nailed to the door of their Oyster Bay home.[1] Shortly after that, the family sold their home in Oyster Bay, taking an apartment at 30 Central Park South in New York City.[3][1] Shortly afterward, they moved in with Emma's mother at East 15th Street.[3] In the summer of 1906, amidst rumors of marital issues, the couple began to live apart—Dresser at the New York Yacht Club and Emma at 166 Madison Avenue.[3] Emma gained custody of the children in a separation hearing around May 1907.[3] On June 21, 1907, Dresser asked for a restraining order to prevent her from taking the children abroad.[3] However, the judge declined to issue the order on the basis that Dresser had deserted the family and was not providing support.[3]

On January 14, 1908, Emma traveled to the "divorce colony" of Sioux Falls, South Dakota where she remained for one day at the Cartaract Hotel.[3] She returned to Sioux Falls in April 1908, this time staying a residence at Prairie Avenue for the six months required for a divorce.[3] On May 1, 1908, she registered for a class in shorthand and typing at the Sioux Falls Business College.[3] Although trying to keep her stay a secret—her phone book listing was for Mrs. A.M.A. Stewart—another would-be divorcee, Mrs. W. Barklie Henry of Philadelphia, told a reporter about Emma's presence in Sioux Falls.[3][38] Always reluctant to speak to the press, Emma said, "I lived with Mr. Dresser until a year and one-half ago when he deserted me. His failure occurred six years ago, which disproves the suspicion that I am separated from him because he lost his money."[3] She also indicated that she was taking the business course because she had two children to support.[3] Emma received her divorce on August 10, 1908, on the grounds of desertion.[38] The hearing was private, with terms for alimony being settled before the hearing.[38] It was later revealed that Dresser tried to gain custody of his children during the divorce.[1] However, Emma stated her husband had shown signs of a mental imbalance since his financial collapse.[1] This claim was denied by Dresser's attorneys, but Emma retained custody.[1] After the divorce, Emma and the children lived at 142 East 40th Street in New York City, with a summer home in Babylon, Long Island.[1][39] Around 1911, Dresser started seeing a doctor for nervous trouble.[1]

On December 22, 1914, Dresser married Mrs. Marcia Walther Baldwin at the Third Reformed Church in Albany, New York.[39] Baldwin was an actress and pianist who had studied dramatic art in Paris and music in Berlin and Frankfort.[1][21][40] She was the widow of Spencer Baldwin and the daughter of German immigrants, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Walther of Brooklyn.[39] She was booked as a piano soloist with the Russian Symphony Orchestra, but broke her hand before the concert.[1] This injury essentially ended to her musical career.[40] Using the name Marcia Walther, she made her stage debut in the title role of August Strindberg's Countess Julia which opened on Broadway on April 28, 1913, for a three-show run.[40] The New York Times called the production "revolting" and noted that Walther was "peculiarly unsuited" to acting.[40] The review continued, "She is not without magnetism, and in occasional quiet passages...her playing justified and held respectful attention. But she seems wholly without the power to express great passion, her speech is not infrequently marked by affectation, her gesture is awkward and restricted, and her general organism is of a kind which in reading roles nothing short of transcendent genius would make effective in the theater."[40] Apparently, this was the end of her Broadway career.[41]

After their honeymoon, the couple stayed in Newport.[1] Their marriage was kept secret until March 1915.[21] In late June 1915, the couple came to New York City where they were looking for an apartment.[1] Marcia stayed with her mother while Dresser took a room at the Delta Psi fraternity house at 434 Riverside Drive in New York City.[21][5][1] The fraternity's members were gone for summer vacations.[5]

On July 10, 1915, Dresser shot himself in the right temple with a .38 caliber revolver at the Delta Psi fraternity house around 3:00 p.m.[1][2][5] He died immediately.[5] He was 52 years old.[1] He was found by his attorney and friend C. W. Gould who rushed to the fraternity house after receiving an "alarming" letter from Dresser at 5:30 p.m.[21] In the letter which had been posted by special delivery at 9:00 a.m. that morning, Dresser said, "I am under a nervous strain so great that I cannot stand it any longer."[5] When Gould arrived at the fraternity house, the door was locked.[21] Shortly afterward steward William Bainbridge arrived and the two men forced the entrance.[5][1] Gould rushed to Dresser's room which was empty.[21] Bainbridge and Gould searched room-by-room until finding the Dresser's body in the third-floor library.[21][1] Bainbridge had left Dresser alone in the fraternity house around 3:00 p.m.[21] No suicide letter or note was found with Dresser or in the fraternity house.[1]

With regards to Dresser's motive for suicide, Gould stated that there were no problems with Marcia.[1] Gould said, "Anybody who has known anything of Mr. Dresser or his affairs for the last 10 years would know that financial difficulties were back of his act."[21] Dresser's finances had worsened over the twelve years since his business failure and he was no longer able "to maintain the standard of living to which he had been accustomed."[1]

After his death, his body was turned over to the mortuary with no funeral plans.[2]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl "D. Leroy Dresser, Once Rich Banker, Commits Suicide. Brother of Mrs. G. W. Vanderbilt and Mrs. John Nicholas Brown Shoots Himself" (PDF). The New York Times. July 11, 1915. p. 1. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "No Dresser Funeral Plans" (PDF). The New York Times. 12 July 1915. p. 14. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Mrs. LeRoy Dresser in Divorce Colony" (PDF). The New York Times. 8 June 1908. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Memorial of Susan E. Leroy.; Tablet Unveiled in Trinity Church, Newport, Yesterday" (PDF). The New York Times. 29 June 1899. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Dresser a Brother of Mrs. Vanderbilt". Greensboro Daily News. July 12, 1915. p. 3. Retrieved May 4, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Miss Pauline Dresser to be Married". The New York Times. October 16, 1897. p. 5. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "American Girl Engaged". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. June 2, 1899. p. 7. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fish and Game Association". Newport Mercury (Newport, Rhode Island). April 18, 1885. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Meyer, H. L. G. Catalog of the Members of the Fraternity of Delta Psi Revised and Corrected to July 1906. New York: Fraternity of Delta Psi, 1906. p. 39. via Google Books.

- ^ "Mr. Leroy Dresser". Boston Evening Transcript. March 3, 1888. p. 10. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Dresser & Co. Fail for $1,250,000" (PDF). The New York Times. 8 March 1903. p. 1. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Arrest Dresser for Misappropriation" (PDF). The New York Times. March 17, 1906. p. 8. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Dresser Figures in Whitlock Bankruptcy" (PDF). The New York Times. November 12, 1903. p. 2. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "City". The New York Tribune. June 11, 1901. p. 6. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Merchants War on Devery". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York). September 30, 1901. p. 2. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "News and Gossip from New York". Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York). October 5, 1901. p. 6. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The President's Callers". Evening Star (Washington, D.C.). January 3, 1902. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University (1902-04-30). "Letter from D. LeRoy Dresser to Theodore Roosevelt". www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org. Theodore Roosevelt Papers. Library of Congress Manuscript Division. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b "New Trust Company". The New York Times. January 8, 1902. p. 14. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Sammis, L. Walter. “The Relation of Trust Companies to Industrial Combinations, as Illustrated by the United States Shipbuilding Company.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 24 (1904): 241–70. via JSTOR, accessed May 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Suicide Due to Money Worries". The Boston Globe. July 11, 1915. p. 2. Retrieved May 4, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Dresser Tells Inside of Shipbuilding Deal" (PDF). The New York Times. October 8, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Signed to Oblige Dresser" (PDF). The New York Times. July 2, 1909. p. 3. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "His Shipbuilding Suit a Surprise to Plaintiff" (PDF). The New York Times. March 25, 1905. p. 10. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ United States Shipping Board and Emergency Fleet Corporation: Hearings Before the Select Committee to Inquire Into the Operations, Policies, and Affairs of the United States Shipping Board and the United States Emergency Fleet Corporation, House of Representatives, Sixty-eighth Congress, First Session, Pursuant to House Resolution 186. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1925. p. 725. via Google Books.

- ^ The National Cyclopedia of American Biography. United States: J. T. White, 1921. p. 431. via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d "Dresser on the Stand" (PDF). The New York Times. June 29, 1909. p. 2. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hill, Jonathan (April 19, 2017). "Crossing the Atlantic: Carl Schenck and Formation of American Forestry" (PDF). p. 70. Duke University. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Referee Against Dresser" (PDF). The New York Times. 12 January 1905. p. 14. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b c "Shipbuilding Trust Case" (PDF). The New York Times. October 26, 1903. p. 9. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Dresser & Co. Will Pay" (PDF). The New York Times. April 9, 1903. p. 2. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Shipbuilding Suits Settled for Cash" (PDF). The New York Times. October 10, 1908. p. 6. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Directors Must Pay Money Dresser Lost" (PDF). The New York Times. September 4, 1909. p. 3. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c "A Day of Many Weddings; Pretty Ceremonies in the City and its Suburbs" (PDF). The New York Times. 21 November 1889. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ "The Burnham Family; Or, Genealogical Records of the Descendants of the Four Emigrants of the Name, who Were Among the Early Settlers in America". Press of Case, Lockwood & Brainard. 1 January 1869. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ "Typhoid Fever". The New York Times. October 4, 1898. p. 9. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New System at Columbia". Boston Evening Transcript. January 11, 1900. p. 5. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Mrs. Leroy Dresser Obtains a Divorce" (PDF). The New York Times. 11 August 1908. p. 1. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b c "D. LeRoy Dresser Kept Wedding Quiet" (PDF). The New York Times. March 5, 1915. p. 9. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "A Revolting Play" (PDF). The New York Times. April 29, 1913. p. 9. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Marcia Walther". Playbill. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch