Environmental communication

Environmental communication is "the dissemination of information and the implementation of communication practices that are related to the environment. In the beginning, environmental communication was a narrow area of communication; however, nowadays, it is a broad field that includes research and practices regarding how different actors (e.g., institutions, states, people) interact with regard to topics related to the environment and how cultural products influence society toward environmental issues".[1]

Environmental communication also includes human interactions with the environment.[2] This includes a wide range of possible interactions, from interpersonal communication and virtual communities to participatory decision-making and environmental media coverage. From the perspective of practice, Alexander Flor defines environmental communication as the application of communication approaches, principles, strategies, and techniques to environmental management and protection.[3][4]

History[edit]

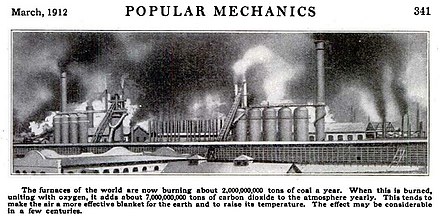

Environmental Communication, breaking off from traditional rhetorical theory, emerged in the United States around the 1980s.[5] Researchers began studying environmental communication as a stand-alone theory because of the way environmental activists used images and wording to persuade their public's. Since then, environmental communication theory has reached multiple milestones including the creation of the journal of environmental communication in 2007.[6]

In academia[edit]

As an academic field, environmental communication emerged from interdisciplinary work involving communication, environmental studies, environmental science, risk analysis and management, sociology, and political ecology.

In his 2004 textbook, Alexander Flor considers environmental communication to be a significant element in the environmental sciences, which he believes to be transdisciplinary. He begins his textbook on environmental communication with a declarative statement: "Environmentalism as we know it today began with environmental communication. The environmental movement was ignited by a spark from a writer’s pen, or more specifically and accurately, Rachel Carson’s typewriter." According to Flor, environmental communication has six essentials: knowledge of ecological laws; sensitivity to the cultural dimension; ability to network effectively; efficiency in using media for social agenda setting; appreciation and practice of environmental ethics; and conflict resolution, mediation and arbitration.[3] In an earlier book published in 1993, Flor and colleague Ely Gomez explore the development of an environmental communication curriculum from the perspectives of practitioners from the government, the private sector, and the academe.[7]

The role of Environmental Communication in education and academia is centered around goals through pedagogy.[8] These are aimed at trying to increase ecological wakefulness, support a variety of practice-based ways of learning and building a relationship of being environmental change advocates.[8]

In general, Environmental skepticism is an increasing challenge for environmental rhetoric.[9]

Climate change communication[edit]

Information Technology and Environmental Communication[edit]

The technological breakthroughs empowered by the appearance of the Internet are also contributing to environmental problems. Air pollution, acid rain, global warming, and the reduction of natural sources are also an outcome of online technologies. Netcraft argued that in the world, there are 7,290,968 web-facing computers, 214,036,874 unique domain names, and 1,838,596,056 websites leading to significant power consumption. Therefore, notions such as “Green Websites” have emerged for helping to tackle this issue. “Green Websites” is “associated with the climate-friendly policies and aims to improve the natural habitat of Earth. Renewable sources, the use of black color, and the highlight of the environmental news are some of the easiest and cheapest ways to contribute positively to climate issues”.[11] The aforementioned term is under the umbrella of “Green Computing,” which is aiming to limit the carbon footprints, energy consumption and benefit the computing performance.

Information and Communications technology aka ICT, has an obsessive amount of environment impacts through different types of disposal of devices and equipment that have been portrayed to give off harmful gasses and Bluetooth waves into the atmosphere that increase the carbon emissions. This has also shown that the technology has been used to minimize energy use, society always wants new technology no matter if it affects the environment good or not, but ICT has been cutting back and putting out better technology for our environment while still being able to communicate through society.[citation needed]

Symbolic action[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2019) |

Environmental communication is also a type of symbolic action that serves two functions:[13] Environmental human communication is pragmatic because it helps individuals and organizations to accomplish goals and do things through communication. Examples include educating, alerting, persuading, and collaborating. Environmental human communication is constitutive because it helps shape human understanding of environmental issues, themselves, and nature. Examples include values, attitudes, and ideologies regarding nature and environmental issues.

In the book Pragmatic Environmentalism: Towards a Rhetoric of Eco-Justice, environmental philosopher Shane Ralston criticizes Cox's pragmatic function of environmental communication for being too shallow and instrumental, recommending instead a deeper account borrowed from Pragmatism: "[A]n even better way to move beyond a conception of pragmatic rhetoric as shallow instrumentalism and deepen the meaning of pragmatic[...] is to look instead to philosophical pragmatism’s other rich resources, for instance, to its fallibilism, experimentalism, and meliorism."[14]

Environmental nature communication occurs when plants actually communicate within ecosystems: "A plant injured on one leaf by a nibbling insect can alert its other leaves to begin anticipatory defense responses."[15] Furthermore, "plant biologists have discovered that when a leaf gets eaten, it warns other leaves by using some of the same signals as animals". The biologists are "starting to unravel a long-standing mystery about how different parts of a plant communicate with one another."[16]

All beings are connected by the Systems Theory, which submits that one of the three critical functions of living systems is the exchange of information with its environment and with other living systems (the other two being the exchange of materials and the exchange of energy). Flor extends this argument, saying: "All living systems, from the simplest to the most complex, are equipped to perform these critical functions. They are called critical because they are necessary for the survival of the living system. Communication is nothing more than the exchange of information. Hence, at its broadest sense, environmental communication is necessary for the survival of every living system, be it an organism, an ecosystem, or (even) a social system."[3]

Environmental Communication plays an integral role in sustainability science. By taking knowledge and putting it into action.[17] Since Environmental Communication is focused on everyday practices of speaking and collaborating, it has a deep understanding in the public discussion of environmental policy. Something that sustainability science has a shortcoming of.[17] Sustainability science requires cooperation between stakeholders and thus requires constructive communication between those stakeholders to create sustainable change.

Limitations[edit]

Robert Cox is a leader in the discipline of environmental communication and its role in the public sphere.[18] Cox covers the importance of Environmental Communication and the role it plays in policy-making processes, advocacy campaigns, journalism, and environmental movements.[18] Something that Cox overlooks in the importance of Environmental communication in the Public Sphere is the role visual and aural communication, electronic and digital media, and perhaps most glaringly, popular culture.[18] Along with the aforementioned limitations the media plays a major role in the conversation around the environment because of the framing effect and the impact that it has on the overall perception of the environment and the discussion surrounding it.[19] Framing is something that has been important to many movements in the past but it is more than just creating slogans and the like. George Lakoff argues in favor of a social movement approach similar to the feminist movement or the civil rights movement.[20]

The field of Environmental Communication also faces challenges of being silenced and invalidated by governments.[21] Environmental communication like many disciplines had challenges with people with opposing views points that make it difficult to spread a certain message. Environmental Communication like many highly polarized topics is prone to confirmation bias which makes it difficult to have compromises in the world of policy making for the environmental crisis.[21] Along with confirmation bias, Echo chambers do much the same thing and are discussed by Christel van Eck who says with respect to environmental communication that echo chambers can reinforce preexisting climate change perceptions. which serve to make it more difficult to engage in real conversations about the topic.[22] Another reason that it can be difficult to communicate about these things is that many people try to use directional motivated reasoning in which they try to find evidence to push a specific narrative on the topic. The effect that this has had on communicating this idea is examined by Robin Bayes and others who say that it can be very detrimental and divisive.[23] One of the things that makes environmental narratives so dangerous is that it changes so often that it is very difficult to keep the information the same as it travels. This according to Miyase Christensen makes it so that the spreading of these narratives can be dangerous.[24]

Environmental Communication faces a variety of challenges in the political environment due to increased polarization.[25] People often feel threatened by arguments that do not align with their beliefs (boomerang effect). These can lead to psychological reactance, counter-arguing, and anxiety.[25] This can cause difficulty in making progress in political change regarding environmental issues. When it comes to the increased polarization of movements regarding the environment some people point to the impact of identity campaigns because of the argument that fear is counterproductive. Robert Brulle argues this point and calls for a shift away from these identity campaigns and moving towards challenge campaigns.[26]

Another limitation of the conversation regarding the environment is the fact that there are multiple agendas being set by different groups in China and the fact that they are different from one another. Along with this the idea that these two different groups are in some sort of a discussion is presented by Xiaohui Wang et. al.[27]

A culture centered approach has been suggested by some like Debashish Munshi. These people argue for enacting change based on the knowledge of older cultures however it has to exist in a way that does not abuse the relationship between the older cultures and our current one which according to Munshi makes it very difficult to enact.[28]

Environmental Communication Theory[edit]

To understand the ways in which environmental communication has an effect on individuals, researchers believe that one's view on the environment shapes their views in a variety of ways. The overall study of environmental communication consists of the idea that nature "speaks." In this field, theories exist in an effort to understand the basis of environmental communication.[29]

Material-Symbolic Discourse[edit]

Researchers view environmental communication as symbolic and material. They argue that the material world helps shape communication as communication helps shape the world.[29] The word environment, a primary symbol in western culture, is used to shape cultural understandings of the material world. This understanding gives researchers the ability to study how cultures react to the environment around them.[29]

Mediating-Human Nature Relations[edit]

Humans react and form opinions based on the environment around them. Nature plays a role in human relations. This theory strives to make a connection between human and nature relations. This belief is at the core of environmental communication because it seeks to understand how nature affects human behavior[30] and identity.[31] Researchers point out that there can be a connection made with this theory and phenomenology.

Applied Activist Theory[edit]

It is difficult to avoid the "call to action" when talking about environmental communication because it is directly linked with issues such as climate change, endangered animals, and pollution. Scholars find it difficult to publish objective studies in this field. However, others argue that it is their ethical duty to inform the public on environmental change while providing solutions to these issues.[29] This idea that it can be damaging to a scientist's reputation to offer up opinions or solutions to the problem of Climate Change has been furthered by research done by Doug Cloud who had findings affirming this idea.[32]

As the following section suggests, there are many divisions of studies and practices in the field of environmental communication, one of which being social marketing and advocacy campaigns. Though this is a broad topic, a key aspect of successful environmental campaigns is the language used in campaign material. Researchers have found that when individuals are concerned & interested about environmental actions, they take well to messages with assertive language; However, individuals who are less concerned & interested about environmental stances, are more receptive to less assertive messages.[33] Although communications on environmental issues often aim to push into action consumers who already perceive the issue being promoted as important, it is important for such message producers to analyze their target audience and tailor messages accordingly.

While there are some findings that there is a problem with scientists advocating for certain positions in a study conducted by John Kotcher and others it was found that there was no real difference between the credibility of scientists regardless of their advocacy unless they directly tried to argue in favor a specific solution to the problem.[34]

Areas of study and practice[edit]

According to J. Robert Cox, the field of environmental communication is composed of seven major areas of study and practice:

- Environmental rhetoric and discourse

- Media and environmental journalism

- Public participation in environmental decision making

- Social marketing and advocacy campaigns

- Environmental collaboration and conflict resolution

- Risk communication

- Representations of nature in popular culture and green marketing[35]

Publications[edit]

Journals[edit]

Peer-reviewed journals related to environmental communication include:

Books[edit]

- Anderson, Alison (1997). Media, Culture and the Environment. London: Routledge

- Anderson, Alison (2014). Media, Environment and the Network Society. Basingstoke: Palgrave

- Boykoff, Maxwell T (2019). Creative (Climate) Communications: Productive Pathways for Science, Policy and Society. London: Oxford University Press

- Corbett, Julia B (2006). Communicating Nature: How We Create and Understand Environmental Messages. Washington, D.C.: Island Press

- Cox, J. Robert (2010). Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications

- Fletcher, C Vail & Jeanette Lovejoy (2018) Natural Disasters and Risk Communication: Implications of the Cascadia Subduction Zone Megaquake. Maryland: Lexington Books

- Flor, Alexander G (2004). Environmental Communication: Principles, Approaches and Strategies of Communication Applied to Environmental Management. Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: University of the Philippines Open University

- Mathur, Piyush (2017). Technological Forms and Ecological Communication: A Theoretical Heuristic. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books

- Ralston, Shane (2013). Pragmatic Environmentalism: Towards a Rhetoric of Eco-Justice. Leicester: Troubador.

- Stephens, Murdoch (2018). Critical Environmental Communication: How Does Critique Respond to the Urgency of Climate Change. Maryland: Lexington Books

See also[edit]

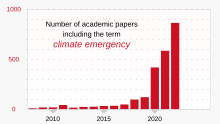

- Climate emergency declaration (includes usage of the term "climate emergency")

- Climate crisis (about usage of the term)

- Communication studies

- List of environmental issues

- List of environmental studies topics

- Lists of environmental publications

- Media coverage of climate change

- Science Communication Observatory

References[edit]

- ^ Antonopoulos, Nikos; Karyotakis, Minos-Athanasios (2020). The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society. Thousands Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 551. ISBN 9781483375533.

- ^ "Environmental Communication: What it is and Why it Matters". Meisner.ca. 2015-11-30. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ a b c Flor, Alexander Gonzalez (2004). Environmental Communication: Principles, Approaches and Strategies of Communication Applied to Environmental Management. Philippines: University of the Philippines Open University.

- ^ Flor, Alexander G. (2004). Environmental Communication: Principles, Approaches, and Strategies of Communication Applied to Environmental Management. University of the Philippines, Open University. ISBN 978-3-11-018968-1.[page needed]

- ^ Harris, Usha (July 2017). "Engaging communities in environmental communication". Pacific Journalism Review. 23: 65–79. doi:10.24135/pjr.v23i1.211.

- ^ Katz-Kimchi, Merav (2015). "Organizing and Integrating Knowledge about Environmental Communication". Environmental Communication (9): 367–369. doi:10.1080/17524032.2015.1042985. S2CID 142087798.

- ^ Flor, Alexander, and Gomez, Ely D., eds. (1993). Environmental Communication: Considerations in Curriculum and Delivery Systems Development. Los Banos, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Banos - Institute of Development Communication.

- ^ a b Cox, James Robert (2018-08-03). "Environmental communication pedagogy and practice". Environmental Education Research. 24 (8): 1224–1227. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1434870. ISSN 1350-4622. S2CID 148692820.

- ^ Jacques, P. (2013). Environmental Skepticism: Ecology, Power and Public Life. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0754671022.

- ^ Osaka, Shannon (30 October 2023). "Why many scientists are now saying climate change is an all-out emergency". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Data source: Web of Science database.

- ^ a b Antonopoulos, Nikos; Karyotakis, Minos-Athanasios; Kiourexidou, Matina; Veglis, Andreas (2019). "Media web-sites environmental communication: operational practices and news coverage". World of Media. 2 (2): 44–63. doi:10.30547/worldofmedia.2.2019.3.

- ^ Murugesan, San (2008). "Harnessing Green IT: Principles and Practices". IT Professional. 10 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1109/MITP.2008.10. S2CID 40947691.

- ^ Abbati, Maurizio (2019). "1 the Environmental Communication Under the Magnifying Lens". Communicating the Environment to Save the Planet. pp. 3–29. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-76017-9_1. ISBN 978-3-319-76016-2. S2CID 159134658.

- ^ Ralston, Shane (1 January 2013). Pragmatic Environmentalism: Towards a Rhetoric of Eco-Justice. Leicester UK. p. 16. ISBN 9781780883786.

- ^ Toyota, Masatsugu; Spencer, Dirk; Sawai-Toyota, Satoe; Jiaqi, Wang; Zhang, Tong; Koo, Abraham J.; Howe, Gregg A.; Gilroy, Simon (2018). "Glutamate triggers long-distance, calcium-based plant defense signaling". Science. 361 (6407): 1112–1115. Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1112T. doi:10.1126/science.aat7744. PMID 30213912. S2CID 52274372.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth (2018-09-13). "Plants communicate distress using their own kind of nervous system". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

- ^ a b Lindenfeld, Laura A.; Hall, Damon M.; McGreavy, Bridie; Silka, Linda; Hart, David (2012-03-01). "Creating a Place for Environmental Communication Research in Sustainability Science". Environmental Communication. 6 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1080/17524032.2011.640702. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 143884272.

- ^ a b c Pedelty, Mark (2015-01-02). "Environmental communication and the public sphere". Environmental Communication. 9 (1): 139–142. doi:10.1080/17524032.2014.1003440. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 144101640.

- ^ Bognar, Julia; Skogstad, Grace; Mondou, Matthieu (2020-11-16). "Media Coverage and Public Policy: Reinforcing and Undermining Media Images and Advanced Biofuels Policies in Canada and the United States". Environmental Communication. 14 (8): 1127–1144. doi:10.1080/17524032.2020.1787479. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 225587113. Retrieved 2023-08-09.

- ^ Lakoff, George (March 2010). "Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment". Environmental Communication. 4 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1080/17524030903529749. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 7254556.

- ^ a b Lester, Libby (2015-07-03). "Three Challenges for Environmental Communication Research". Environmental Communication. 9 (3): 392–397. doi:10.1080/17524032.2015.1044065. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 145437342.

- ^ van Eck, Christel W.; Mulder, Bob C.; van der Linden, Sander (2021-02-17). "Echo Chamber Effects in the Climate Change Blogosphere". Environmental Communication. 15 (2): 145–152. doi:10.1080/17524032.2020.1861048. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 232105642.

- ^ Bayes, Robin; Bolsen, Toby; Druckman, James N. (2023-01-02). "A Research Agenda for Climate Change Communication and Public Opinion: The Role of Scientific Consensus Messaging and Beyond". Environmental Communication. 17 (1): 16–34. doi:10.1080/17524032.2020.1805343. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 225309649.

- ^ Christensen, Miyase; Åberg, Anna; Lidström, Susanna; Larsen, Katarina (2018-01-02). "Environmental Themes in Popular Narratives". Environmental Communication. 12 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1421802. ISSN 1752-4032.

- ^ a b Ma, Yanni; Hmielowski, Jay D. (2022-02-17). "Are You Threatening Me? Identity Threat, Resistance to Persuasion, and Boomerang Effects in Environmental Communication". Environmental Communication. 16 (2): 225–242. doi:10.1080/17524032.2021.1994442. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 244671120.

- ^ Brulle, Robert J. (March 2010). "From Environmental Campaigns to Advancing the Public Dialog: Environmental Communication for Civic Engagement". Environmental Communication. 4 (1): 82–98. doi:10.1080/17524030903522397. ISSN 1752-4032.

- ^ Wang, Xiaohui; Chen, Liang; Shi, Jingyuan; Tang, Hongjie (2023-04-03). "Who Sets the Agenda? the Dynamic Agenda Setting of the Wildlife Issue on Social Media". Environmental Communication. 17 (3): 245–262. doi:10.1080/17524032.2021.1901760. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 234860296. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ Munshi, Debashish; Kurian, Priya; Cretney, Raven; Morrison, Sandra L.; Kathlene, Lyn (2020-07-03). "Centering Culture in Public Engagement on Climate Change". Environmental Communication. 14 (5): 573–581. doi:10.1080/17524032.2020.1746680. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 219408243.

- ^ a b c d Milstein, Tema (2009). "Environmental Communication Theories". Encyclopedia of Communication Theory (1): 344–348.

- ^ Comfort, Suzannah; Park, Young Eun (2018). "On the Field of Environmental Communication: A Systematic Review of the Peer-Reviewed Literature". Environmental Communication. 12 (7): 862–875. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1514315. S2CID 149717289.

- ^ Milstein, T. & Castro-Sotomayor, J. (2020). Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity. London, UK: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351068840

- ^ Cloud, Doug (2020-08-17). "The Corrupted Scientist Archetype and Its Implications for Climate Change Communication and Public Perceptions of Science". Environmental Communication. 14 (6): 816–829. doi:10.1080/17524032.2020.1741420. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 216203931.

- ^ Kronrod, Ann; Grinstein, Amir; Wathieu, Luc (January 2012). "Go Green! Should Environmental Messages be So Assertive?". Journal of Marketing. 76 (1): 95–102. doi:10.1509/jm.10.0416. S2CID 168002678.

- ^ Kotcher, John E.; Myers, Teresa A.; Vraga, Emily K.; Stenhouse, Neil; Maibach, Edward W. (2017-05-04). "Does Engagement in Advocacy Hurt the Credibility of Scientists? Results from a Randomized National Survey Experiment". Environmental Communication. 11 (3): 415–429. doi:10.1080/17524032.2016.1275736. ISSN 1752-4032. S2CID 85511071.

- ^ Cox, J. Robert. (2010). Environmental Communication And The Public Sphere. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, pp.??[page needed]

Further reading[edit]

- Katz-Kimchi, Merav; Goodwin, Bernhard (3 July 2015). "FORUM: Organizing and Integrating Knowledge about Environmental Communication". Environmental Communication. 9 (3): 367–369. doi:10.1080/17524032.2015.1042985. S2CID 142087798.

- Tema Milstein, "Environmental Communication Theories," in Stephen W. Littlejohn and Karen A. Foss (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Communication Theory, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2009, pp. 344–349. http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/communicationtheory/n130.xml

- Tema Milstein and Gabi Mocatta, "Environmental Communication Theory and Practice for Global Transformation: An Ecocultural Approach," in Yoshitaka Miike and Jing Yin (Eds.), The Handbook of Global Interventions in Communication Theory, New York: Routledge, 2022, pp. 474–490. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781003043348-35

- Harris, Usha Sundar (21 July 2017). "Engaging communities in environmental communication". Pacific Journalism Review. 23 (1): 65. doi:10.24135/pjr.v23i1.211.

- Comfort, Suzannah Evans; Park, Young Eun (3 October 2018). "On the Field of Environmental Communication: A Systematic Review of the Peer-Reviewed Literature". Environmental Communication. 12 (7): 862–875. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1514315. S2CID 149717289.

External links[edit]

- International Environmental Communication Association (IECA) – a professional association for environmental communication practitioners, teachers, and scholars

- ClimateClock: clock counting down to 1,5°C temperature rise

- Lexington book series on Environmental Communication and Nature: Conflict and Ecoculture in the Anthropocene

- Talk.Eco: Resources for Environmental Communicators Archived 2022-09-24 at the Wayback Machine – a website featuring curated resources for environmental communication professionals

- Environmental Communication: What it is and Why it Matters by Mark Meisner

- Environmental Communication: Research Into Practice – an online course

- Bibliography of books in environmental communication by Mark Meisner

- ECOresearch Network – Research Network on Environmental Online Communication

- Indications: Environmental Communication blog (inactive), 2010–2012

- About the Environmental Communication Division – The International Communication Association Environmental Communication Division

- Communication et environnement, le pacte impossible Archived 2016-02-16 at the Wayback Machine by Thierry Libaert

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch