Fifth of July (New York)

The Fifth of July is a historic celebration of an Emancipation Day in New York, marking the culmination of the state's 1827 abolition of slavery after a gradual legislative process. State law passed under Governor Daniel D. Tompkins a decade earlier had designated Independence Day, the Fourth of July, as when abolition would take effect, but the danger of racist violence led African Americans to celebrate on the following day instead.

These celebrations continued on July 5 for years in New York, although in a reduced fashion after 1834, with the effect of both the anti-abolitionist riots and the British Slavery Abolition Act. The tradition largely merged into August 1 British abolition anniversary celebrations, though it was noted as late as 1859. The holiday was revived and recognized by the state for the first time in 2020, as an Abolition Commemoration Day observed on the second Monday in July.

History[edit]

African Americans in New York had made preparations from at least March 1827, reported in the newly established Freedom's Journal. Nathaniel Paul at Albany led a meeting that "Resolved, That whereas the 4th day of July is the day that the National Independence of this country is recognized by white citizens, we deem it proper to celebrate the 5th".[1]

On July 4, 1827, New York's black churches held services of prayer and thanksgiving. William Hamilton gave a speech at the Mother AME Zion Church (then in its original home of Church and Leonard Street), the site of the largest celebration. He discussed the historic context of the event and the 1741 incident as examples of the troubled past, celebrated the emancipation law as a redemption, and proclaimed that "no more shall negro and slave be synonymous."[2] Attendees at the events dispersed quietly, fearful that whites in their own Independence Day revels would pick fights.[2]

The largest celebration in New York City on July 5, 1827 saw 2,000–4,000 celebrants gather at St. John's Park, led by marshal Samuel Hardenburgh.[3] Numerous groups participated; the first in the parade line was the New York African Society for Mutual Relief. From the park, they paraded to Zion Church and then to City Hall on Broadway where they met Mayor William Paulding Jr.[4][2] Nathaniel Paul spoke at Albany on the same day in 1827.[1] There was internal community debate about how visible public celebrations should be.[5] Henry Highland Garnet and James McCune Smith recollected participating in the first celebration in New York City in their youths, the latter recalling diverse African diaspora celebrants, including from the Caribbean and Africa.

The seventh annual observance was documented in an 1833 anonymous travelogue by an Englishman, believed to be the Liverpool merchant James Boardman.[6]

In June 1834, the National Convention of Free People of Colour held at Chatham Street Chapel-Theatre passed a resolution against July 5 parades, preferring private community events held on July 4 for reasons of safety.[7][8] The following month, racially integrated celebrations at the same venue on July 7 (which were already disrupted from July 4) were attacked in an incident that sparked the New York anti-abolitionist riots.

Legacy[edit]

The New York black community continued to reserve the Fourth of July for a bitter reflection on the gap between America's promise and its reality, and the Fifth of July for their own personal celebration.[2] Celebrations declined after 1834.[9] The tradition remained relevant, but largely merged into local commemorations of the August 1 Emancipation Day in the British Empire, first observed in New York in 1838 as part of a growing national embrace among African Americans.[7]

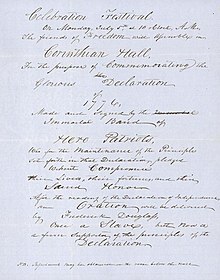

Frederick Douglass, also a regular of August 1 celebrations,[7] gave a July 5, 1852 oration in Rochester on "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?", a seminal text seen by some scholars as embodying a distinctive "Fifth of July" conception of patriotism.[10][11] The speech did not explicitly reference the custom of July 5 observances, however. Later mentions include a dedicated event in Auburn in 1856, and a note about a declining but still extant tradition by William Cooper Nell in 1859.[9]

An 1836 play in London by William Leman Rede starred Manhattan-born blackface performer Thomas D. Rice as his stereotypical "Jim Crow" character, and focused on a mockery of Fifth of July celebrations.[12] Literary critics have speculated that the 1851 novel Moby-Dick's relatively realistic depiction of African American dance in the character of Pip was inspired by Fifth of July and related parades held near author Herman Melville's childhood home.[13]

The New York branches of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History supported "Abolition Commemoration Day" as a state holiday on the second Monday in July, and it was recognized by the state legislature along with Juneteenth in 2020.[14][15]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Levine, Robert S. (October 17, 2014). "Fifth of July: Nathaniel Paul and the Construction of Black Nationalism". In Carretta, Vincent; Gould, Philip (eds.). Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 242–60. ISBN 978-0-8131-5946-1.

- ^ a b c d Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 546–547. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

- ^ "New-York, July 13" (PDF). Freedom's Journal. Vol. I, no. 18. July 13, 1827. p. 71. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 11, 2015.

- ^ Mirrer, Louise; Horton, James Oliver; Rabinowitz, Richard (July 3, 2005). "Opinion | Happy Fifth of July, New York!". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Harris, Leslie M. (August 1, 2004). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863. University of Chicago Press. pp. 122–128. ISBN 978-0-226-31775-5. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Boardman, James; world, Citizen of the (1833). America, and the Americans ... Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longman. ISBN 978-0-608-43808-5.

- ^ a b c Kachun, Mitch; Kachun, Mitchell Alan (March 1, 2006). Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808-1915. Liverpool University Press. pp. 53–56. ISBN 978-1-55849-528-9.

- ^ Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Color, Fourth Annual (1834 : New York (1834). "Minutes of the Fourth Annual Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Colour, in the United States; held by adjournments in the Asbury Church, New York, from the 2nd to the 12th of June, inclusive, 1834". Bell, Howard H., ed. (1969) Minutes and Proceedings of the National Negro Conventions, 1830–1864. New York: Arno Press. Archived from the original on May 14, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gravely, William B. (Winter 1982). "The Dialectic of Double-Consciousness in Black American Freedom Celebrations, 1808-1863". The Journal of Negro History. 67 (4): 302–317. doi:10.2307/2717532. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2717532. S2CID 149884386.

- ^ Mirrer, Louise; Horton, James Oliver; Rabinowitz, Richard (July 3, 2005). "Opinion | Happy Fifth of July, New York!". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ Britton-Purdy, Jedediah (July 1, 2022). "Opinion | Democrats Need Patriotism Now More Than Ever". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey H.; Nathans, Heather S. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of American Drama. OUP USA. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-19-973149-7.

- ^ Stuckey, Sterling (2009). African Culture and Melville's Art: The Creative Process in Benito Cereno and Moby-Dick. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-19-537270-0.

- ^ AmNews Staff Reports (July 30, 2020). "Assembly passes legislation recognizing Abolition Commemoration Day and Juneteenth in New York State". New York Amsterdam News. Archived from the original on July 3, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ "NY Legislature passes Juneteenth emancipation holiday". Daily Sentinel. July 24, 2020. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch