History of lobbying in the United States

The history of lobbying in the United States is a chronicle of the rise of paid advocacy generally by special interests seeking favor in lawmaking bodies such as the United States Congress. Lobbying has usually been understood as activity by paid professionals to try to influence key legislators and executives, which is different from the right for an individual to petition the government. It has been around since the early days of the Republic, and affects every level of government from local municipal authorities to the federal government in Washington. In the nineteenth century, lobbying was mostly conducted at the state level, but in the twentieth century, there has been a marked rise in activity, particularly at the federal level in the past thirty years. While lobbying has generally been marked by controversy, there have been numerous court rulings protecting lobbying as free speech. At the same time, the courts have made no final ruling on whether the petition clause of the US Constitution covers lobbying.[1]

Beginnings[edit]

When the Constitution was crafted by Framers such as James Madison, their intent was to design a governmental system in which powerful interest groups would be rendered incapable of subduing the general will. According to Madison, a faction was "a number of citizens, whether amounting to a minority or majority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community." Madison considered factions as dangerous, since they threatened to bring about tyranny if their control became too great. Madison, writing in the Federalist Papers, suggested that factions could be thwarted by requiring them to compete with other factions, and therefore the powerful force of one faction could be counteracted by another faction or factions.[2] Today, the term "special interest" has often been equated with Madison's sense of "faction". In addition, the Constitution sought to protect other freedoms, such as free speech.

Accordingly, some believe the ability of individuals, groups, and corporations to lobby the government is protected by the right to petition[3] in the First Amendment. It is protected by the Constitution as free speech; one accounting was that there were three Constitutional provisions which protect the freedom of interest groups to "present their causes to government",[4] and various decisions by the Supreme Court have upheld these freedoms over the course of two centuries.[5] Even corporations have been considered in some court decisions to have many of the same rights as citizens, including their right to lobby officials for what they want.[5] As a result, the legality of lobbying took "strong and early root" in the new republic.[4]

On the other hand, lobbying is a political process, a way to argue for or against legislation. It is often done in private, behind closed doors. This is very different from petitioning. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this was an open, transparent process in state legislatures, and later in Congress. Petitions would be read and considered in public sessions.[1] Thus, "State governments criminalized lobbying, and courts were quick to void contracts for lobbying services as violative of public policy because they saw the sale of one’s own personal, informal access as a corruption of petitioning."[1]

During the nineteenth century, generally, most lobbying happened within state legislatures, since the federal government, while having larger jurisdiction, did not handle many matters pertaining to the economy, and it did not do as much legislating as the state governments.[4] When lobbying did happen in those days, it was often "practiced discreetly" with little or no public disclosure.[4] By one account, more intense lobbying in the federal government happened from 1869 and 1877 during the administration of President Grant[6] near the start of the so-called Gilded Age. The most influential lobbies wanted railroad subsidies and a tariff on wool. At the same time in the Reconstruction South, lobbying was intense near the state legislatures, especially regarding railroad subsidies, but it also happened in areas as diverse as gambling. For example, Charles T. Howard of the Louisiana State Lottery Company actively lobbied state legislators and the governor of Louisiana for the purpose of getting a license to sell lottery tickets.[7][8]

- The Louisiana State Lottery Company lobbied the Louisiana state legislature and governor extensively to win permission to run a lottery business in New Orleans from 1866 onwards

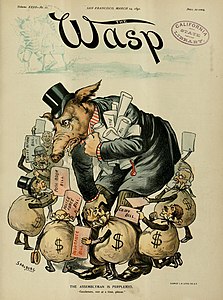

- 1891 cartoon about lobbying an American assemblyman

Twentieth century[edit]

In the Progressive Era from the 1880s to the 1920s, reformers frequently blamed lobbyists as corrupting politics.[9] Already the idea that lobbying should become more exposed was beginning to take hold. In 1928, there was criticism of the American Tariff League's payments, in concert with the Republican National Committee, to help elect Herbert Hoover; the League was criticized for failing to report its expenditures and how it had hired two "Washington correspondents", that is, two lobbyists.[10]

During this time, Col. John Thomas Taylor was described by reporter Clarence Woodbury of The American Magazine, as "the most successful lobbyist in the history of the world." Thomas was the chief lobbyist for the American Legion. Between 1919 and 1941, he had been able to have 630 different veterans' bills passed through Congress that benefited ex-servicemen by more than 13 billion dollars.[11] In 1932, when President Herbert Hoover described "a locust swarm of lobbyists" that haunted the halls of Congress, Time magazine named Taylor as one of the agents who was paid $10,000 per year for their actions.[12] When Taylor returned to the U.S. after World War II, he was not satisfied with the original version of the G.I. Bill of Rights and was able to have it amended in ten different places.[13]

In 1953, after a lawsuit involving a congressional resolution authorizing a committee to investigate "all lobbying activities intended to influence, encourage, promote, or retard legislation," the Supreme Court narrowly construed "lobbying activities" to mean only "direct" lobbying––which the Court described as "representations made directly to the Congress, its members, or its committees". It contrasted it with indirect lobbying: efforts to influence Congress indirectly by trying to change public opinion. The Court rejected a broader interpretation of "lobbying" out of First Amendment concerns,[14] and thereby affirmed the earlier decision of the appeals court. The Supreme Court ruling was:

In support of the power of Congress it is argued that lobbying is within the regulatory power of Congress, that influence upon public opinion is indirect lobbying, since public opinion affects legislation; and that therefore attempts to influence public opinion are subject to regulation by the Congress. Lobbying, properly defined, is subject to control by Congress, ... But the term cannot be expanded by mere definition so as to include forbidden subjects. Neither semantics nor syllogisms can break down the barrier which protects the freedom of people to attempt to influence other people by books and other public writings. ... It is said that lobbying itself is an evil and a danger. We agree that lobbying by personal contact may be an evil and a potential danger to the best in legislative processes. It is said that indirect lobbying by the pressure of public opinion on the Congress is an evil and a danger. That is not an evil; it is a good, the healthy essence of the democratic process. ...

— Supreme Court decision in Rumely v. United States[15]

Several political trends emerged from an interplay of factors in the second half of the twentieth century:

- Congresspersons seeking reelection were able to win easily in most cases since rules regarding gerrymandering[16] and franking privileges usually favored incumbents rather than challengers; several studies found that the probability of congresspersons winning reelection was consistently over 90%.[17][18][19] Congress made the rules, including ones about free mailings. Congresspersons could give themselves generous pensions and benefits packages, and could determine the salaries of members; in 2006, salaries were $165,200.[20]

- Expensive campaigns. But winning reelection meant spending huge sums on expensive media, particularly television advertising, and congresspersons seeking reelection found themselves having to spend much of their time raising money instead of governing.[21] In 1976, the average cost of running for a House seat was $86,000; by 2006, it was $1.3 million.[22] Running for Senate was even pricier, with an average cost in 2006 of $8.8 million.[22]

- Lobbyists, who used to focus on persuading lawmakers after election, began to assist congresspersons with reelection fundraising, often via political action committees or PACs.[21] A lobbyist for a cooperative of many businesses could form these relatively new types of organizations to supervise the distribution of monies to the campaigns of "favored members of Congress".[22] Corporate PACs became prominent quickly until today when they could be described as ubiquitous. There have been reports that the influence of money, in general, has "transformed American politics".[22]

- Partisanship became more prevalent, becoming particularly uncompromising and dogmatic,[21] beginning during the 1980s. A report in The Guardian suggested that widespread gerrymandering led to the creation of many hard-to-challenge or "safe seats", so that when real contests come along, "party activists duke it out among hardcore supporters in primaries", and that this exacerbates sometimes bitter partisanship.[16]

- Complexity. This was partly a result of a continuing shift of legislative authority from state governments to Washington, and partly as a result of new technologies and systems. It became difficult for voters or watchdog groups to monitor this activity since it became harder to follow or even comprehend. Complexity encouraged more specialized lobbying, often with more than one agency affected by any one piece of legislation, and encouraging lobbyists to become familiar with the often-intricate details and history of many issues.[4] Executive branch agencies added a new layer of rule-making to congressional legislation. The economy expanded.

- Earmarks. Special provisions called earmarks could be tacked onto a law, often at the last minute and usually without much oversight, which allowed congresspersons to direct specific funding to a particular cause, often benefiting a project in their home district. Such practices increased Washington's habit of pork barrel politics. Lobbyists such as Gerald Cassidy helped congresspersons understand how to use earmarks to channel money to specific causes or interests, initially towards Cassidy's university clients.[22] Cassidy found earmarks to be a particularly effective way to channel grant money to universities.[22] According to one report in the Washington Post by journalist Robert G. Kaiser, Cassidy invented the idea of "lobbying for earmarked appropriations" which "fed a system of interdependence between lobbyists and Congress".[22]

- Staffers. The growth in lobbying meant that congressional aides, who normally lasted in their positions for many years or sometimes decades, now had an incentive to "go downtown", meaning become a lobbyist, and accordingly the average time spent working for a congressperson shortened considerably to perhaps a few years at most.[22]

As a result of a new political climate, lobbying activity exploded during the last few decades. Money spent on lobbying increased from "tens of millions to billions a year," by one estimate.[22] In 1975, total revenue of Washington lobbyists was less than $100 million; by 2006, it exceeded $2.5 billion.[23] Lobbyists such as Cassidy became millionaires while issues multiplied, and other practitioners became similarly wealthy.[22] One estimate was that Cassidy's net worth in 2007 exceeded $125 million.[22]

Cassidy made no bones about his work. He liked to talk about his ability to get things done: winning hundreds of millions in federal dollars for his university clients, getting Ocean Spray Cranberry juice into school lunches, helping General Dynamics save the billion-dollar Seawolf submarine, smoothing the way for the president of Taiwan to make a speech at Cornell despite a U.S. ban on such visits.

— Journalist Robert G. Kaiser in the Washington Post, 2007[23]

Another trend emerged: the revolving door. Before the mid 1970s, it was rare that a congressperson upon retirement would work for a lobbying firm and when it did occasionally happen, it "made eyebrows rise".[23] Prior to the 1980s lawmakers rarely became lobbyists as the profession was generally considered 'tainted' and 'unworthy' for once-elected officials such as themselves; in addition lobbying firms and trade groups were leery of hiring former members of Congress because they were reputed to be 'lazy as lobbyists and unwilling to ask former colleagues for favors'. By 2007, there were 200 former members of the House and Senate were registered lobbyists.[23] New higher salaries for lobbyists, increasing demand and a greater turnover in Congress and a 1994 change in the control of the House contributed to a change in attitude about the appropriateness of former elected officials becoming lobbyists. The revolving door became an established arrangement.

In the new world of Washington politics, the activities of public relations and advertising mixed with lobbying and lawmaking.[24]

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Balogh, Brian "'Mirrors of Desires': Interest Groups, Elections, and the Targeted Style in Twentieth-Century America," in Meg Jacobs, William J. Novak, and Julian Zelizer, eds. The Democratic Experiment: New Directions in American Political Theory, (2003), 222–49

- Clemens, Elisabeth S. The People's Lobby: Organizational Innovation and the Rise of Interest-Group Politics in the United States, 1890–1925 (1997)

- Hansen, John M. Gaining Access: Congress and the Farm Lobby, 1919–1981 (1991)

- Loomis, Christopher M. "The Politics of Uncertainty: Lobbyists and Propaganda in Early Twentieth-Century America," Journal of Policy History Volume 21, Number 2, 2009 in Project MUSE

- Thompson, Margaret S. The "Spider Web": Congress and Lobbying in the Age of Grant (1985) on 1870s

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Lobbying and the Petition Clause". Stanford Law Review. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Alt URL

- ^ Ronald J. Hrebenar; Bryson B. Morgan (2009). "Lobbying in America". ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-112-1. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

see Preface page xv

- ^ "The Right to Petition". Illinois First Amendment Center. Archived from the original on 2013-04-11.

- ^ a b c d e Donald E. deKieffer (2007). "The Citizen's Guide to Lobbying Congress: Revised and Updated". Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-718-0. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

see Ch.1

- ^ a b Evangeline Marzec of Demand Media (2012-01-14). "What Is Corporate Lobbying?". Chron.com. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ^ Margaret S. Thompson, The "Spider Web": Congress and Lobbying in the Age of Grant (1985)

- ^ New York Times - May 27, 1895

- ^ "A NOTED LOTTERY MAN DEAD.; CAREER OF CHARLES T. HOWARD, OF THE LOUISIANA COMPANY". The New York Times. June 1, 1885. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ^ Elisabeth S. Clemens, The People's Lobby: Organizational Innovation and the Rise of Interest-Group Politics in the United States, 1890–1925 (1997)

- ^ "National Affairs: Light on Lobbying, Cont". Time Magazine. Feb 3, 1930. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ^ "Sigma Pi In The News, The Veterans' One-Man Army" (PDF). The Emerald of Sigma Pi. Vol. 33, no. 3. November 1946. p. 130.

- ^ "National Affairs. Locusts". Time. May 16, 1932.

- ^ "John Thomas Taylor Dies" (Press release). Indianapolis, Indiana: American Legion News Service. May 28, 1965. pp. 179–180. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41 (1953)

- ^ Rumely v. United States, 197 F.2d 166, 173-174, 177 (D.C. Cir. 1952).

- ^ a b Paul Harris (19 November 2011). "'America is better than this': paralysis at the top leaves voters desperate for change". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-01-17.

- ^ Perry Bacon Jr. (August 31, 2009). "Post Politics Hour: Weekend Review and a Look Ahead". Washington Post. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ David C. Huckabee -- Analyst in American National Government -- Government Division (March 8, 1995). "Reelection rate of House Incumbents 1790-1990 Summary (page 2)" (PDF). Congressional Research Service -- The Library of Congress. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "How To Clean Up The Mess From Inside The System, A Plea--And A Plan--To Reform Campaign Finance Before It's Too". NEWSWEEK. October 28, 1996. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ Salaries of Members of Congress (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved on August 12, 2007.

- ^ a b c Barry Hessenius (2007). "Hardball Lobbying for Nonprofits: Real advocacy for nonprofits in the new century". Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-8202-5. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Robert G. Kaiser; Alice Crites (research contributor) (2007). "Citizen K Street: How lobbying became Washington's biggest business -- Big money creates a new capital city. As lobbying booms, Washington and politics are transformed". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2011-09-06. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

{{cite news}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d Robert G. Kaiser; Alice Crites (research contributor) (2007). "Citizen K Street: How lobbying became Washington's biggest business -- Big money creates a new capital city. As lobbying booms, Washington and politics are transformed". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2012-05-24. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

{{cite news}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ Woodstock Theological Center (2002). "The Ethics of Lobbying: Organized Interests, Political Power, and the Common Good". Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-8784-0905-X. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

(see page 1 of "The Ethics of Lobbying" chapter)

External links[edit]

- First Street Research Group powered by First Street reports on the lobbying industry

- LobbyWatch from The Center for Public Integrity

- Lobbying Database from OpenSecrets

- Clean Up Washington Public Citizen project

- Lobbying Info archives of Public Citizen project

- CQ MoneyLine

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch