Islamic Government

| |

| Author | Ruhollah Khomeini; translated by Hamid Algar |

|---|---|

| Country | Iran and United Kingdom |

| Language | Translated into English |

| Subject | Islam and state |

| Publisher | Manor Books, Mizan Press, Alhoda UK |

Publication date | 1970, 1979, 1982, 2002[1] |

| Pages | 139 pages |

| ISBN | 964-335-499-7 |

| OCLC | 254905140 |

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Iran |

|---|

|

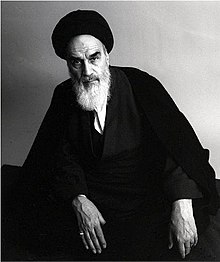

Islamic Government (Persian: حکومت اسلامی, romanized: Ḥokūmat-i Eslāmī),[2] or Islamic Government: Jurist's Guradianship (Persian: حکومت اسلامی ولایت فقیه, romanized: Ḥokūmat-i Eslāmī Wilāyat-i Faqīh)[3] is a book by the Iranian Shi'i Muslim cleric/jurist, and revolutionary, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. First published in 1970, it is perhaps the most influential document written in modern times in support of theocratic rule.

The book argues that government should/must be run in accordance with traditional Islamic law (sharia), and for this to happen a leading Islamic jurist (faqīh) must provide political "guardianship" (wilayat in Arabic, velāyat in Persian) over the people and nation. Following the Iranian Revolution, a modified form of this doctrine was incorporated into the 1979 Constitution of Islamic Republic of Iran;[4] drafted by an assembly made up primarily by disciples of Khomeini, it stipulated he would be the first faqih "guardian" (Vali-ye faqih) or "Supreme Leader" of Iran.[5]

History[edit]

| Part of a series on Islamism |

|---|

| |

While in exile in Iraq in the holy city of Najaf, Khomeini gave a series of 19 lectures on Islamic Government to a group of his students from January 21 to February 8, 1970. Notes of the lectures were soon made into a book that appeared under three different titles: The Islamic Government, Authority of the Jurist, and A Letter from Imam Musavi Kashef al-Qita[6] (to deceive Iranian censors). The small book (fewer than 150 pages) was smuggled into Iran and "widely distributed" to Khomeini supporters before the revolution.[7]

Controversy surrounds how much of the book's success came from its persuasiveness, religiosity, etc., and how much from the success of the political movement of the author (Khomeini), who is generally considered to have been the "undisputed" leader of the Iranian Revolution. Many observers of the revolution maintain that while the book was distributed to Khomeini's core supporters in Iran, Khomeini and his aides were careful not to publicize the book or the idea of wilayat al-faqih to outsiders,[8][9] knowing that groups crucial to the revolution's success—secular and Islamic modernist Iranians—were under the impression the revolution was being fought for democracy, not theocracy. It was only when Khomeini's core supporters had consolidated their hold on power that wilayat al-faqih was made known to the general public and written into the country's new Islamic constitution.[10]

The book has been translated into several languages including French, Arabic, Turkish and Urdu.[2] The English translation that is most commonly found, that is considered (by at least one source—Hamid Dabashi) to be the "only reliable" translation",[11] and that is approved by the Iranian government, is that of Hamid Algar, an English-born convert to Islam, scholar of Iran and the Middle East, and supporter of Khomeini and the Islamic Revolution.[12] It can be found in Algar's book Islam and Revolution, in a stand-alone edition published in Iran by the "Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imam Khomeini's Works",[13] which was also published by Alhoda UK,[14] and is available online.[15]

The one other English language edition of the book, also titled Islamic Government, is a stand-alone edition, translated by the U.S. government's Joint Publications Research Service. Algar considers this translation to be an inferior to his own—being "crude" and "unreliable" and based on Arabic translation rather than the original Persian—and claims its publication by Manor books is "vulgar" and "sensational" in its attacks on the Ayatollah Khomeini.[16] (Whether the original language of the Islamic Government lectures was Persian or Arabic is disputed.)[11]

Contents[edit]

Scope[edit]

Khomeini and his supporters before the revolution were from Iran, his movement was focused on Iran, and most of his criticisms of non-Islamic government refer to the imperial government of Iran. However, Islamic government was (eventually) to be universal, not limited to one country in the Islamic world and not limited to the Islamic world.[17] According to Khomeini, this would not be that difficult because "if the form of government willed by Islam were to come into being, none of the governments now existing in the world would be able to resist it; they would all capitulate".[17]

Importance of Islamic Government[edit]

- Protecting religion

Without a leader to serve the people as "a vigilant trustee", enforcing "law and order", Islam would fall victim "to obsolescence and decay", its "rites and institutions", "customs and ordinances" disappearing or mutating as "heretical innovators", "atheists and unbelievers" subtracted and added "things from it".[18]

Providing justice[edit]

Khomeini believed that the need for governance of the faqih was obvious to good Muslims. That "anyone who has some general awareness of the beliefs and ordinances of Islam" would "unhesitatingly give his assent to the principle of the governance of the faqih as soon as he encounters it," because the principle has "little need of demonstration, for anyone who has some general awareness of the beliefs and ordinances of Islam ...."[19]

Nonetheless he sets out several reasons why Islamic government is necessary:

- To prevent "encroachment by oppressive ruling classes on the rights of the weak," and plundering and corrupting the people for the sake of "pleasure and material interest";[20]

- To prevent "innovation" in Islamic law "and the approval of the anti-Islamic laws by sham parliaments",[20] and so;

- To preserve "the Islamic order" and keep all individuals on "the just path of Islam without any deviation,"[20]

- to "reverse" the decline of Islam brought about by absence of "executive power" in the hands of "just fuqaha ... in the land inhabited by Muslims";[21]

- And to destroy "the influence of foreign powers in the Islamic lands".[20][note 1]

The operation of Islamic government is superior to non-Islamic government in many ways. Khomeini sometimes compares it to (allegedly) un-Islamic governments in general throughout the Muslim world and more often contrasts it specifically with the government of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi—though he doesn't mention the Shah by name.

Compared to the justice, impartiality, thrift, self-denial, and general virtue of the early leaders of Islam we know of from literature passed down over 1000 years, "Non-Islamic government..."

- is mired in red tape thanks to "superfluous bureaucracies,"[22]

- suffers from "reckless spending", and "constant embezzlement", in the case of Iran, forcing it to "request aid or a loan from" abroad and hence "to bow in submission before America and Britain"[22]

- has excessively harsh punishments (such as capital punishment for the possession of small amounts of heroin),[23]

- creates an "unjust economic order" which divides the people "into two groups: oppressors and oppressed",[24]

- though it may be made up of elected representatives does not "truly belong to the people" in the case of Muslim countries.[25]

While some might think the complexity of the modern world would move the Muslims of 1970 to learn from countries that have modernized ahead of them, and even borrow laws from them, this is not only un-Islamic but also entirely unnecessary. The laws of God (Shariah), cover "all human affairs ... There is not a single topic in human life for which Islam has not provided instruction and established a norm."[26] As a result, Islamic government will be much easier than some might think.

The entire system of government and administration, together with necessary laws, lies ready for you. If the administration of the country calls for taxes, Islam has made the necessary provision; and if laws are needed, Islam has established them all. ... Everything is ready and waiting.[27]

For this reason Khomeini declines "to go into details" on such things as "how the penal provisions of the law are to be implemented".[28]

Required by Islam[edit]

In addition to the reasons above offered for why the guardianship of the jurist would function better than secular non-Islamic government, Khomeini also gives much space to doctrinal reasons that (he argues) establish proof that the rule of jurists is required by Islam.

No sacred texts of Shia (or Sunni) Islam include a straightforward statement that the Muslim community should be ruled over by Islamic jurists or Islamic scholars.[29] Traditionally, Shia Islam follows a pivotal Shi'i hadith where Muhammad passed down his power to command Muslims to his cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, the first of twelve "Imams". His descendants are a line of would-be rulers, never in a position to actually rule, that stopped with the occultation (disappearance) of the last Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, in 939 CE (see: Muhammad al-Mahdi#Birth and early life according to Twelver Shi'a). While waiting for the reappearance of that Twelfth Imam, Shia jurists have tended to stick to one of three approaches to the state: cooperate with it, try to influence policies by becoming active in politics, or most commonly, remaining aloof from it.[30][note 2]

Khomeini says there are "numerous traditions [hadith] that indicate the scholars of Islam are to exercise rule during the Occultation",[32] and tries to prove this by explicating several Quranic verses and hadith of the Shi'a Imams. The first proof he offers is an analysis of a saying attributed to the first Imam, 'Ali who in addressing a well-connected judge he considered corrupt,[33] said:

The seat you are occupying is filled by someone who is a prophet, the legatee of a prophet, or else a sinful wretch.[32]

While this might sound like ʿAli is simply remonstrating against the judge who had exceeded his authority and sinned, Khomeini reasons that hadith's use of the term judge must refer to a trained jurist (fuqaha), as the "function of a judge belongs to just fuqaha [plural for faqih]" ',[34] and since trained jurists are neither sinful wretches nor prophets, "we deduce from the tradition quoted above that the fuqaha are the legatees";[35] and since legatees of Muhammad, such as Imams, have the same power to command and rule Muslims as Muhammad did, it is therefore demonstrated that the saying, `The seat you are occupying is filled by someone who is a prophet, the legatee of a prophet, or else a sinful wretch,` proves that Islamic jurists have the power to rule Muslims.

Other examples the follow include

- "Obey those among you who have authority" (Q.4:59)

where the authorities in the verse are religious judges according to Khomeini;[36]

- putting together two hadith of Ali:

- "those who transmit my statements and my traditions and teach them to the people" (which must mean, according to Khomeini, trained Islamic legal scholars) are my successors;

- "all believers" should obey my successors",

indicates to Khomeini that Ali's transmitters are jurists, and so are his successors, and so must be obeyed.

- The Seventh Imam had praised religious judges as "the fortress of Islam",[36] which must mean the fuqaha are entrusted with preserving Islam, which means they have an active social role, according to Khomeini.[37]

- The twelfth Imam had preached that future generations should obey those who knew his teachings since those people were his representatives among the people in the same way as he was God's representative among believers;[36] which must mean that the ulama are not only "the point of reference" for points of Islamic law but also for "contemporary social problems", according to Khomeini.[37]

- The Sixth Imam said "The ulama are the heirs of the prophets. The prophets did not leave a single dinar or dirham for an inheritance. Rather they left knowledge as an inheritance and whosoever takes from it, has taken an abundant share"; Khomeini interprets this to mean that the ulama have not only inherited knowledge from the prophets, but also "the Prophets' authority" to rule.[38]

- God had created sharia to guide the Islamic community (ummah), the state to implement sharia, and faqih to understand and implement sharia.[36]

Not only is the rule of Islamic jurists and obedience toward them an obligation of Islam, it is as important a religious obligation as any a Muslim has. "Our obeying holders of authority" like Islamic jurists "is actually an expression of obedience to God."[39] Preserving Islam "is more necessary even than prayer and fasting"[40] and (Khomeini argues) without Islamic government, Islam cannot be preserved.

It is also the duty of Muslims to "destroy" "all traces" of any other sort of government other than true Islamic governance, because these are "systems of unbelief".[41]

Islamic Government[edit]

The basis of Islamic government is said to be justice, which is defined as following Sharia (Islamic law) exclusively.[29] Therefore, the theory goes, those holding government posts should have extensive knowledge of Sharia (Islamic jurists being trained in sharia are such people), and the country's ruler should be a faqih[note 3] who "surpasses all others in knowledge" of Islamic law and justice[43] — known as a marja`—as well as having intelligence and administrative ability.

While this faqih rules, it might be said that the ruler is actually sharia law itself because, "the law of Islam, divine command, has absolute authority over all individuals and the Islamic government. Everyone, including the Most Noble Messenger [Muhammad] and his successors, is subject to law and will remain so for all eternity ... "[25]

"The governance of the faqih" is equivalent to "the appointment of a guardian for a minor." Just as God is said to have established Muhammad as the "leader and ruler" of early Muslims, "making obedience to him obligatory, so, it is claimed, the fuqaha (plural of faqih) must be leaders and rulers" over Muslims today.[44] While the "spiritual virtues" and "status" of Muhammad and the Imams are considered greater than those of contemporary faqih, their power is not, because this virtue "does not confer increased governmental powers".[45]

Khomeini says that Islamic government "truly belongs to the people", not in the sense of being made up of representatives chosen by the people through an election. but because it enforces Islamic laws recognized by Muslims as "worthy of obedience,"[25] and it is "not constitutional in the current sense of word, i.e., based on the approval of laws in accordance with the opinion of the majority" with executive, legislative and judicial branches of government; in an Islamic government he says the legislative assembly has been replaced by "a simple planning body" a legislature being unnecessary because "no one has the right to legislate ... except ... the Divine Legislator",[25] and God has already provided all the laws anyone needs in the sharia.[27][note 4]

Islamic government raises revenue "on the basis of the taxes that Islam has established - khums, zakat ... jizya, and kharaj."[48] [note 5] This will be plenty because "khums is a huge source of income".[49]

Islamic Government, says Khomeini, will be just and will be unsparing with "troublesome" groups that cause "corruption in Muslim society," and damage "Islam and the Islamic state," giving the example of Muhammad, who killed the men of the Bani Qurayza tribe and enslaved the women and children after the tribe collaborated with Muhammad's enemies and then refused to convert to Islam.[50] [51]

Khomeini says that Islamic government will follow 'Ali, whose seat of command was simply the corner of a mosque[52] threatened to have his daughter's hand cut off if she did not pay back a loan from the treasury[53] and who "lived more frugally than the most impoverished of our students,"[54] and that it will follow the "victorious and triumphant" armies of early Muslims who set "out from the mosque to go into battle" and "fear[ed] only God".[55] They will follow the Quranic command: "prepare against them whatever force you can muster and horses tethered" [Quran 8:60]. In fact, he says, "if the form of government willed by Islam were to come into being, none of the governments now existing in the world would be able to resist it; they would all capitulate".[17]

Why has Islamic Government not been established?[edit]

If the need for governance of the faqih is obvious to "anyone who has some general awareness of the beliefs and ordinances of Islam", why has it not yet been established? Khomeini spends a large part of his book explaining why.[19]

The "historical roots" of the opposition are Western unbelievers who want

to keep us backward, to keep us in our present miserable state so they can exploit our riches, our underground wealth, our lands and our human resources. They want us to remain afflicted and wretched, and our poor to be trapped in their misery ... they and their agents wish to go on living in huge palaces and enjoying lives of abominable luxury.[56]

Foreign experts have studied our country and have discovered all our mineral reserves -- gold, copper, petroleum, and so on. They have also made an assessment of our people's intelligence and come to the conclusion that the only barrier blocking their way are Islam and the religious leadership.[57]

These Westerners "have known the power of Islam themselves for it once ruled part of Europe, and ... know that true Islam is opposed to their activities."[58] Westerns have set about deceiving Muslims, using their native "agents" to spread the falsehood that "that Islam consists of a few ordinances concerning menstruation and parturition".[59] Planning to promote the vices of fornication, alcohol drinking and charging interest on loans "in the Islamic world", Westerners have led Muslims to believe that "Islam has laid down no laws for the practice of usury, ... for the consumption of alcohol, or for the cultivation of sexual vice".[60] Ignorance is such a state that when "Islam commands its followers to engage in warfare or defense in order to make men submit to laws that are beneficial for them and kills a few corrupt people", people ask why such violence is necessary.[56]

The enemies of Islam target the vulnerable young: "The agents of imperialism are busy in every corner of the Islamic world drawing our youth away from us with their evil propaganda."[61]

This imperialist attack on Islam is not some ad hoc tactic to assist the imperial pursuit of power or profit, but an elaborate, 300-year-long plan.

The British imperialists penetrated the countries of the East more than 300 years ago. Being knowledgeable about all aspects of these countries, they drew up elaborate plans for assuming control of them.[62]

In addition to the British there are the Jews:

From the very beginning, the historical movement of Islam has had to contend with the Jews, for it was they who first established anti-Islamic propaganda and engaged in various stratagems, and as you can see, this activity continues down to the present.[63]

We must protest and make the people aware that the Jews and their foreign backers are opposed to the very foundations of Islam and wish to establish Jewish domination throughout the world.[61]

While the main danger of unbelievers comes from foreign (European and American) imperialists, non-Muslims in Iran and other Muslim countries pose a danger too,

centers of evil propaganda run by the churches, the Zionists, and the Baha'is in order to lead our people astray and make them abandon the ordinances and teaching of Islam ... These centers must be destroyed.[64]

The imperialist war against Islam has even penetrated, (in Khomeini's view), the seminaries where the scholars of Islam are trained. There, Khomeini notes, "If someone wishes to speak about Islamic government and the establishment of the Islamic government, he must observe the principles of taqiyya, [i.e. dissimulation, the permission to lie when one's life is in danger or in defence of Islam], and count upon the opposition of those who have sold themselves to imperialism".[56] If these "pseudo-saints do not wake up" Khomeini suggests, "we will adopt a different attitude toward them."[65]

As for those clerics who serve the government, "they do not need to be beaten much," but "our youths must strip them of their turbans."[66]

Influences[edit]

Traditional Islamic[edit]

Khomeini himself claims Mirza Hasan Shirazi, Mirza Muhammad Taqi Shriazi, Kashif al-Ghita,[28] as clerics preceding him who made what were "in effect"[28] government rulings, thus establishing de facto Islamic Government by Islamic jurists. Some credit "earlier notions of political and juridical authority" in Iran's Safavid period. Khomeini is said to have cited nineteenth-century Shi'i jurist Mulla Ahmad Naraqi (d. 1829) and Shaikh Muhammad Hussain Naini (d. 1936) as authorities who held a similar view to himself on the political role of the ulama.[29][67] An older influence is Abu Nasr Al-Farabi, and his book, The Principles of the People of the Virtuous City, (al-madina[t] al-fadila,[note 6] which has been called "a Muslim version of Plato's Republic").[68]

Another influence is said to be Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr, a cleric and author of books on developing Islamic alternatives to capitalism and socialism, whom Khomeini met in Najaf.[69][note 7]

Non-traditional and non-Islamic[edit]

Other observers credit the "Islamic Left," specifically Ali Shariati, as the origin of important concepts of Khomeini's Waliyat al-faqih, particularly abolition of monarchy and the idea that an "economic order" has divided the people "into two groups: oppressors and oppressed."[24][70][71] The Confederation of Iranian Students in Exile and the famous pamphlet Gharbzadegi by the ex-Tudeh writer Jalal Al-e-Ahmad are also thought to have influenced Khomeini.[72] This is in spite of the fact that Khomeini loathed Marxism in general,[73] and is said to have had misgivings about un-Islamic sources of some of Shariati's ideas.[citation needed]

Khomeini reference to governments based on constitutions, divided into three branches, and containing planning agencies, also belie a strict adherence to precedents set by the rule of the Prophet Muhammad and Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, 1400 years ago.[74][75]

Scholar Vali Nasr believes the ideal of an Islamic government ruled by the ulama "relied heavily" on Greek philosopher Plato's book The Republic, and its vision of "a specially educated `guardian` class led by a `philosopher-king`".[76]

Reception[edit]

Doctrinal[edit]

Velayat-e Faqih has been praised as a "masterful construction of a relentless argument, supported by the most sacred canonical sources of Shi'i Islam ..."[77]

The response from high-level Shi'a clerics to Velayat-e Faqih was far less positive. Of the dozen Shia Grand Ayatollahs alive at the time of the Iranian Revolution, only one besides Khomeini — Hussein-Ali Montazeri — approved of Khomeini's concept. He would later disavow it entirely in 1988.[78][note 8] When Khomeini died in 1989, the Assembly of Experts of Iran felt compelled to amend the constitution to remove the requirement that his successor as Supreme Leader be one of jurists who surpass "all others in knowledge" of Islamic law and justice[43] (one of the Marja' mentioned above) "knowing well" that all the senior Shi'i jurists "distrusted their version of Islam".[79] Grand Ayatollah Abul-Qassim Khoei, the leading Shia ayatollah at the time the book was published, rejected Khomeini's argument on the grounds that

- The authority of faqih — is limited to the guardianship of widows and orphans — could not be extended by human beings to the political sphere.

- In the absence of the Hidden Imam (the 12th and last Shi'a Imam), the authority of jurisprudence was not the preserve of one or a few fuqaha.[80]

Another prominent Shi'i cleric who went on record about the doctrine of Velayat-e Faqih was the late Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah of Lebanon -- "widely seen as the 'godfather'" of the Iranian-backed Hezbollah, and one of only three Shia Maraji of Lebanon before he died in 2010. Despite having initially supported the Revolution, Fadlallah criticized what he saw as the absolute power the Iranian clergy ruled with,[81] and called for a system of checks and balances that would prevent the scholars from becoming dictators.[81] In a 2009 interview, he stated "without hesitation":

I don't believe that Welayat al-Faqih has any role in Lebanon. Perhaps some Lebanese commit themselves to the policy of the Guardian Jurist, as some of them commit themselves to the policy of the Vatican [Lebanon's large Maronite community is Catholic]. My opinion is that I don't see the Guardianship of the Jurist as the definitive Islamic regime.[82][83]

Khomeini cited two earlier clerical authorities — Mulla Ahmad Naraqi and Shaikh Muhammad Hussain Naini (mentioned above) — as holding similar views to himself on the importance of the ulama holding political power, but neither made "it the central theme of their political theory as Khomeini does," although they may have hinted "at this in their writings",[29] according to Baháʼí scholar of Shia Islam, Moojan Momen. Momen also argues that the hadith Khomeini quotes in support of his concept of velayat-e faqih, either have "a potential ambiguity which makes the meaning controversial," or are considered `weak` (da'if) by virtue of their chain of transmitters.[84]

In a religion where innovation (bida) is a menace to be constantly on guard for, Iranian historian Ervand Abrahamian writes that Khomeini's ideas "broke sharply" from Shi'i traditions.[85] Discussion/debate had gone on and off for "eleven centuries" over what approach Shi'a should take towards the state—aloofness or some kind of cooperation varying from grudging to obedient.[30][31] But until the appearance of Khomeini's book, "no Shi'i writer ever explicitly contended that monarchies per se were illegitimate or that the senior clergy had the authority to control the state."[86] Khomeini himself had adopted the traditional Shia attitude of refraining from criticizing the monarch (let alone calling him illegitimate) for much of his career, and even after bitterly attacking Muhammad Reza Shah in the mid-1960s didn't attack monarchy as such until his lectures on Islamic Government in 1970.[87] Though Islamic Government implicitly threatened clerical opponents of rule by faqih, for decades before, Khomeini had been "extremely close", (serving as the teaching assistant and personal secretary), to Hossein Borujerdi, the premier Shia cleric of his age, known for being conservative and "highly apolitical".[88] Scholar of Islam Vali Nasr describes Khomeini's concept as reducing Shi'ism "to a strange (and as it would turn out violent) parody of Plato", I.e. Plato's Republic.[76]

Functional[edit]

Islamic Government is criticized on utilitarian grounds (as opposed to religious doctrine), by those who argue that Islamic government as established in Iran by Khomeini has simply not done what Khomeini said Islamic government by jurists would do.[89] The goals of ending poverty,[note 9] corruption, [note 10] national debt,[note 11] harsh punishments,[note 12] or compelling un-Islamic government to capitulate before the Islamic government's armies,[note 13] have not been met. But even more modest and basic goals like downsizing the government bureaucracy,[note 14][97] using only senior religious jurists or marjas for the post of faqih guardian/Supreme Leader,[98][note 15] or implementing sharia law and protecting it from innovation,[100] have eluded the regime. While Khomeini promised, "the entire system of government and administration, together with the necessary laws, lies ready for you.... Islam has established them all,"[101] once in power Islamists found many frustrations in their attempts to implement the sharia, complaining that there were "many questions, laws and operational regulations ... that received no mention in the shari'a."[note 16] Disputes within the Islamic Government compelled Khomeini himself to proclaim in January 1988 that the interests of the Islamic state outranked "all secondary ordinances" of Islam, even "prayer, fasting, and pilgrimage."[103]

- Other complaints

When a campaign started to install velayat-e faqih in the new Iranian constitution, critics complained that Khomeini had made "no mention" of velayat-e faqih "in the proclamations he issued during the revolution",[104] that he had become the leader of the revolution promising to advise, rather than rule, the country after the Shah was overthrown, as late as 1978 while in Paris "he explicitly stated that rather than seeking or accepting any official government position, he would confine himself to the supervisory role of a guide in order to pursue the society's best interest",[105] when in fact he had developed his theory of rule by jurists rather than by democratic elections, and spread it among his followers years before the revolution started;[106] a complaint that some continue to make.[107] The severe loss of prestige for the fuqaha (Islamic jurists) as a result of dissatisfaction with the application of clerical rule in Iran has been noted by many.[108] "In the early 1980s, clerics were generally treated with elaborate courtesy. Nowadays [in 2002], clerics are sometimes insulted by schoolchildren and taxi drivers and they quite often put on normal clothes when venturing outside" the holy city of "Qom."[109][110] According to journalist David Hirst, the Islamist government in Iran

has turned people in ever increasing numbers not only against the mullahs but also against Islam itself. The signs are everywhere, from the fall in attendance at religious schools to the way parents give pre-Islamic, Persian names to their children. If they are looking for authenticity, Iranians now chiefly find it in nationalism, not in religion.[111]

As of early October 2022, "women and men, Persians and minorities, students and workers" in Iran are said to be "united ... against the mullahs' rule",[112] to ”have made up their minds, ... they don't want reform, they want regime change". [113]

Notes[edit]

- ^ All page numbers refer to Hamid Algar's book, Islam and Revolution, Writings and Declarations Of Imam Khomeini (Mizan, 1981).

- ^ Abrahamian offers three slightly different options: shunning the authorities as usurpers, grudging acceptance of them, wholehearted acceptance -- especially if the state was Shi'i.[31]

- ^ Khomeini's English translator defines a faqih as a person "learned in the principles and ordinances of Islamic law, or more generally, in all aspects of the faith."[42]

- ^ The Islamic Republic of Iran does have a legislature, though some have argued it has been kept in a very subordinate position in keeping with Khomeini's idea of wilayat al-faqih,[46] and Iran's executive, parliament, and judiciary branches "are overseen by several bodies dominated by the clergy".[47]

- ^

- khums is a traditional Islamic required religious obligation of any Muslims to pay one-fifth of their acquired wealth from certain sources toward specified causes;

- zakat is the required religious obligation of alms giving and one of the pillars of Islam. It is customarily 2.5% of a Muslim's total savings and wealth above a minimum amount known as nisab each lunar year;

- jizya is a tax on permanent non-Muslim residents but has no set percentage or amount; and

- kharaj is a type of traditional individual Islamic tax on agricultural land and its produce.[48]

- ^ It has been translated by Richard Walzer as Al-Farabi on the Perfect state, pp. 34-35, 172.

- ^ Al-Sadr is author of Falsafatuna ("Our Philosophy") and Iqtisaduna ("Our Economics").[69]

- ^ See, for example, Reza Zanjani.

- ^ In the first six years after the overthrow of the Shah (from 1979 through 1985), The Iranian government's "own Planning and Budget Organization reported that ... absolute poverty rose by nearly 45%!" [90]

- ^ After the mayor of Iran's largest city Tehran was arrested for corruption in 1998, ex-President Rafsanjani] said in a sermon `Graft has always existed, there are always people who are corrupt....` [91])

- ^ Khomeini himself did not run up debt but in the decade after his death, under his faqih guardian successor Iran not only went back into debt, but built it up to almost four times the putatively shameful debt the monarchy left behind in 1979. Spending that Iranian economists criticized as "reckless."[92]

- ^ In 1979 Revolutionary Judge Sadegh Khalkhali ordered the execution of 20 persons found guilty of trafficking in drugs. Over ... several weeks, he sent scores of alleged drug smugglers, peddlers, users and others to their death, often on the flimsiest evidence. By the end of August, some 200 persons had been executed on Khalkhali's orders. This figure rose considerably before" Khalkhali was ousted on unrelated charges.[93])

- ^ On the start of Iran's war with Saddam Hussein's secular state of Iraq, Khomeini stated there were no conditions for a truce except that "the regime in Baghdad must fall and must be replaced by an Islamic Republic"[94]

Six years, hundreds of thousands of Iranian lives, and $100's of billions later, faced with desertions and resistance against the conscription, Khomeini signed a peace agreement stating "... we have no choice and we should give in to what God wants us to do ... I reiterate that the acceptance of this issue is more bitter than poison for me, but I drink this chalice of poison for the Almighty and for His satisfaction."[95] - ^ "Khomeini had to preside over a state bureaucracy three times larger than that of Mohammad Reza Shah."[96]

- ^ On April 24, 1989, Article 109 of the Iranian constitution, requiring that the Leader be a marja'-e taqlid, was removed. New wording in constitutional articles 5, 107, 109, 111, required him to be `a pious and just faqih, aware of the exigencies of the time, courageous, and with good managerial skills and foresight.` If there are a number of candidates, the person with the best `political and jurisprudential` vision should have the priority.`

According to biographer Baqer Moin, "The change was immense. [Khomeini's] theory of Islamic government was based on the principle that the right to rule is the exclusive right of the faqih, the expert on Islamic law."[99] - ^ Ayatollah Behesti speaking in the Assembly of Experts in 1979,[102]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist

- ^ a b Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.25

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.11

- ^ Iranian Government Constitution, English Text Archived 2013-08-19 at the Wayback Machine| iranonline.com

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.33

- ^ Dabashi, Theology of Discontent, 1993: p.437

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 1999: p.157

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran between two revolutions, 1982: p.478-9

- ^ What Happens When Islamists Take Power? The Case of Iran - Clerics, (Gems of Islamism)

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 1999: p.218

- ^ a b Dabashi, Theology of Discontent (1993), p.583

- ^ Q&A: A conversation with Hamid Algar| By Russell Schoch | California Alumni Association| June 2003

- ^ Khomeini, Ayatullah Sayyid Imam Ruhallah Musawi, Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist, Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imam Khomeini's Works, n.d.

- ^ Khomeini (2002). Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist. Alhoda. ISBN 9789643354992. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ Islamic Government| Imam Khomeini| Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imam Khomeini's Works (International Affairs Division)| Translator and Annotator: Hamid Algar |Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.25-6

- ^ a b c Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.122

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.52-3

- ^ a b Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.27

- ^ a b c d Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.54

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.80

- ^ a b Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.58

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.33

- ^ a b Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.49

- ^ a b c d Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.56

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.29-30, also p.44

- ^ a b Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.137-38

- ^ a b c Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.124

- ^ a b c d Momen, Introduction to Shi'i Islam, 1985: p. 196.

- ^ a b Momen, Introduction to Shi'i Islam, 1985: p. 193.

- ^ a b Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.18-19

- ^ a b Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.81

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.81, 158

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.82

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.84

- ^ a b c d Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.24-25

- ^ a b Momen, Introduction to Shi'i Islam, 1985: p. 198.

- ^ Momen, Introduction to Shi'i Islam, 1985: p. 199.

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.91

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.75

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.48

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.150

- ^ a b Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.59

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.63

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.62

- ^ Schirazi, The Constitution of Iran (1997), p. 295.

- ^ "Iran. Government and society Constitutional framework". Britannica. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ a b Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.45

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.44-5

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.89

- ^ Ansary, Tamim (2009). Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes. ISBN 9781586486068.

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.86

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.130

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.57

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.131

- ^ a b c Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.34

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.139-40

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.140

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.29-30

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.31-2

- ^ a b Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.127

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.139, also p.27-28, p.34, p.38

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.27-28

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.128

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.143

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.145

- ^ Dabashi, Hamid. `Early propagation of Wiliyat-i Faqih and Mullah Ahmad Naraqi`. in Nasr, Dabashi and Nasr (eds.). Expectations of the Millennium, 1989, pp. 287-300.

- ^ Kadri, Sadakat (2012). Heaven on Earth: A Journey Through Shari'a Law from the Deserts of Ancient Arabia ... Macmillan. p. 95. ISBN 9780099523277.

- ^ a b The Columbia World Dictionary of Islamism, ed by Roy Olivier and Antoine Sfeir, 2007, pp. 144-5.

- ^ Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini, (2001) p.79, 162

- ^ Dabashi, Theology of Discontent, 1993: p.473

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.23

- ^ Khomeini, Sahifeh-ye Nur, Vol. I, p.229

- ^ Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini, (2001) p.?

- ^ Dabashi, Theology of Discontent, 1993: p.439, 461

- ^ a b Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.126

- ^ Dabashi, Theology of Discontent, 1993: p. 447.

- ^ Roy, The Failure of Political Islam, (1994), pp. 173-4.

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.34

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 1999: p. 158.

- ^ a b "Fadlallah's Death Leaves a Vacuum in the Islamic World". Middle East Online. Archived from the original on 2012-04-03. Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ^ Pollock, Robert L. (March 14, 2009). "A Dialogue with Lebanon's Ayatollah". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "Mixed legacy of Ayatollah Fadlallah". BBC News. 4 July 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

While he [Fadlallah] backed the Iranian revolution, he did not support the Iranian invention of the concept of Wilayet al-Faqih, which gives unchallengeable authority in temporal matters to the Supreme Leader, currently Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who was only a mid-ranking cleric when he attained the leadership.

- ^ Momen, Introduction to Shi'i Islam, 1985: pp. 197-8.

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.3

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.19

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.21

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.8-9

- ^ What Happens When Islamists Take Power? The Case of Iran, (Gems of Islamism)

- ^ Jahangir Amuzegar, `The Iranian Economy before and after the Revolution,` Middle East Journal 46, n.3 (summer 1992): 421), quoted in Reinventing Khomeini : The Struggle for Reform in Iran by Daniel Brumberg, University of Chicago Press, 2001 p.130)

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (c. 2000). Persian Mirrors : the Elusive Face of Iran. Simon and Schuster. p. 327. ISBN 9780743217798.

- ^ The Last Revolution by Robin Wright c2000, p.279

- ^ Bakhash, Shaul (1984). The Reign of the Ayatollahs : Iran and the Islamic Revolution. New York: Basic Books.

- ^ . (p.126, In the Name of God : The Khomeini Decade by Robin Wright c1989)

- ^ Tehran Radio, 20 July 1988 from Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah by Baqer Moin, p.267

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.55

- ^ Arjomand, Turban for the Crown (1988), p.173

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: pp. 34-5.

- ^ Moin, Khomeini, 1999: pp. 293-4.

- ^ "The Western Mind of Radical Islam" by Daniel Pipes, First Things, December 1995

- ^ Khomeini, Islamic Government, 1981: p.137

- ^ Schirazi, The Constitution of Iran (1997): pp. 161-174.

- ^ Keyhan, January 8, 1988

- ^ algar, hamid; hooglund, eric. "VELAYAT-E FAQIH Theory of governance in Shi ʿite Islam". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ MAVANI, HAMID (September 2011). "Ayatullah Khomeini's Concept of Governance (wilayat al-faqih) and the Classical Shi'i Doctrine of Imamate". Middle Eastern Studies. 47 (5): 808. doi:10.1080/00263206.2011.613208. S2CID 144976452.

- ^ Abrahamian, Iran between two revolutions, 1982: p.534-5

- ^ "Democracy? I meant theocracy", by Dr. Jalal Matini, Translation & Introduction by Farhad Mafie, August 5, 2003, The Iranian,

- ^ Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton, (2005), p. 10.

- ^ Who Rules Iran?. Christopher de Bellaigue. New York Review of Books. June 27, 2002.

- ^ "Young Iranians knock turbans off clerics' heads in protest of regime". stuff.co.nz. 4 November 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ David Hirst (18 February 2000). "Opinion. Islamism, in Decline, Awaits a Wake-Up Call From Voters in Iran". New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Iran: will the protests bring change?". eurotopics. 11 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Parisa Hafezi (6 October 2022). "Analysis: Braced to crush unrest, Iran's rulers heed lessons of Shah's fall". Reuters.

Sources[edit]

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran between two revolutions. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691101345.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1993). "Khomeinism". Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic. California: University of California Press. ISBN 0520081730. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Arjomand, Said Amir (1988). Turban for the Crown : The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195042580.

- Dabashi, Hamid (2006). Theology of Discontent : The Ideological Foundations of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. New York University Press. ISBN 9781412839723.

- Demichelis, Marco, "Governance", in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014, Vol I, pp. 226–229.

- Khomeini, Ruhollah (1979). Islamic Government. Ḥukūmah al-Islāmīyah.English. Translated by Joint Publications Research Service. Manor Books. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Khomeini, Ruhollah (1981). Algar, Hamid (ed.). Islam and Revolution : Writing and Declarations of Imam Khomeini. Translated by Algar, Hamid. Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press. ISBN 9781483547541.

- Ayatullah Ruhullah al-Musawi al-Khomeini (2012). "3. Islamic Government (The Book)". Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist (PDF). The Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imām Khomeini’s Works. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- Moin, Baqer (1999). Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9781466893061.

- Momen, Moojan (1985). An Introduction to Shi'i Islam. New Haven, CT; London, England: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300035314.

- Roy, Olivier (1994). "The Failure of Political Islam". The Failure of Political Islam. Translated by Volk, Carol. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674291409.

- Schirazi, Asghar (1997). The Constitution of Iran : politics and the state in the Islamic Republic. New York, NY: I.B. Tauris.

External links[edit]

- Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist Ayatullah Ruhullah al-Musawi al-Khomeini - XKP |www.feedbooks.com [full text]

- GOVERNANCE OF THE JURIST. ISLAMIC GOVERNMENT IMAM KHOMEINI | The Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imam Khomeini's Works (International Affairs Department) [full text]

- Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist: Velayat-e Faqeeh [Original Version]

- "Democracy? I meant theocracy"

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch