Israhel van Meckenem

Israhel van Meckenem (c. 1445 – 10 November 1503), also known as Israhel van Meckenem the Younger, was a German printmaker and goldsmith, perhaps of a Dutch family origin.

He was the most prolific engraver of the fifteenth century and an important figure in the early history of old master prints. In total, he produced over 620 engravings, most of which were copies of other prints; they represent about 20% of print production by all Northern European artists in the period of his working life. His career lasted long enough for him to copy Dürer prints.

He was active from 1465 until his death, and continued to work as a goldsmith; there are some surviving pieces, and many documented commissions from the city of Bocholt. He probably trained in engraving with Master E. S. in South Germany, and may well have been with him at his death c. 1467, since he acquired and reworked forty-one of the master's plates. Another two hundred of van Meckenem's "own" prints were also copies of Master E. S. engravings. He copied many other printmakers, but it is thought that he engraved some 150 of his own original compositions.

Life[edit]

His birth date is merely an estimate. Recent guesses range from the early 1430s to 1450. His father arrived in Bocholt, Germany, near the border of the Netherlands, in 1457, and though his place of birth is uncertain, Joachim von Sandrart referred to him as Israel von Mecheln, and Karel van Mander referred to him as Israel van Mentz.[1][2] He was the son of Israhel van Meckenem the Elder, also a goldsmith, who settled in Bocholt. Attempts have been made to identify the father as the Master of the Berlin Passion, an early engraver, but this remains uncertain. Some writers also assign to the father works traditionally given to the son. The very unusual name "Israhel" suggests the family may have had Jewish origins, but Israhel the Younger was buried in a church, and it might not have been possible for Jews to work as goldsmiths. The "van" suggests a Dutch origin for the family; various places in Germany and the Netherlands have been suggested as "Meckenem", as no place generally called exactly that existed at the time. The Master of the Berlin Passion probably worked mainly in the Netherlands, so his identification with Israhel Senior would have implications for the issue of the family origin.

Israhel van Meckenem probably trained initially as a goldsmith and engraver with his father, before travelling to work with Master E. S., the leading Northern European engraver of the day. His earliest dated print comes from 1465, and indicates that he created it in Cleves, modern Kleve, on the Dutch border and then Dutch-speaking, where the family had moved. In 1470 he is documented as working in Bamberg in Bavaria; he returned to Bocholt by about 1480, where he remained for the rest of his life.

He continued to work at goldsmithing. Some surviving pieces are widely accepted as his and many commissions from the Bocholt council are documented between 1480 and 1498. He was evidently a prosperous and established figure in the town. One of his prints is a double portrait of himself and his wife, Ida, whom he married in the late 1480s;[3] another print is believed by some to show his father. He is documented in various lawsuits against neighbours, and Ida was fined for "unseemly speech" as well as for "mocking and scolding public officials".

He was buried in the Georgskirche in Bocholt.

Work[edit]

As well as the very numerous copies of Master E. S.'s prints, described above, he copied prints by the Housebook Master,[4] including some now otherwise lost, Martin Schongauer, and many other German engravers. His famous and very fine late series on the Life of the Virgin appears to have been based on drawings by Hans Holbein the Elder or his workshop, and he may have entered into a regular commercial relationship with Holbein.[5]

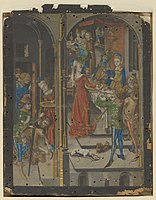

However, some 20% or more of his prints, around 150, seem to be original compositions. His early works were fairly crude, but in the 1480s he developed an effective personal style and made increasingly large and finished works. His own compositions are often very lively, and take a great interest in the secular life of his day. One famous print, supposed to illustrate the story of St John the Baptist and Salome, pushes the specific incidents of the story far in the background to allow space for a scene of court dancers, dressed in the height of contemporary fashion, which takes up most of the plate.[6]

He was sophisticated in self-presentation, signing later prints with his name and town, and producing the first self-portrait print of himself and his wife, which was also the first portrait print of an identifiable person. Some plates seem to have been reworked more than once by his workshop, or produced in more than one version, and many impressions have survived, so his ability to distribute and sell his prints was evidently equally well developed. He was apparently the first to issue engraved (as opposed to woodcut) indulgences, apparently "bootlegged version[s] ... never subject to papal review"; one print promises 20,000 years reduction of time in Purgatory per set of prayers, increased in a second state to 45,000 years.[7]

In the Heures de Charles d'Angoulême, an important manuscript showing the links between printmaking and illumination in the late 15th century, Robinet Testard incorporated sixteen of van Meckenem's prints, gluing them directly on to the vellum then overpainting.[8]

- Dance at Herod's Court, c. 1490, at 21.4 x 31.8 cm (8 7/16 x 12 1/2 in.) his largest print.

- The Falconer and the Lady, from the series Scenes of Daily Life

- Woman Spinning and Visitor

- The Fool and the Lady

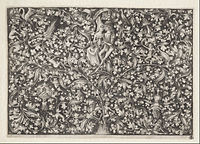

- Ornament print with pair of lovers

- Head of an Oriental

- Hand-coloured Kiss of Judas from Passion series, Heures de Charles d'Angoulême

- Annunciation from the Life of the Virgin series (with Visitation above.

- Hand-coloured Beheading of St. John the Baptist

- The Holy Family with St. Anne

Notes[edit]

- ^ Israel von Mecheln in Sandrart's Teutsche Akademie

- ^ Israel van Mentz in van Mander's Schilder-boeck

- ^ Israhel van Meckenem, Self-portrait and Wife, The British Museum

- ^ Israhel van Meckenem, Joust of Two Wild Men Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Artfinder

- ^ Parshall, 57

- ^ Israhel van Meckenem, The Dance at the Court of Herod Archived 2009-01-11 at the Wayback Machine, Artfinder

- ^ Parshall, 56-58

- ^ Matthews, Anne (1986). "The use of prints in the Hours of Charles d'Angoulême". Print Quarterly. 3 (1): 4–18. JSTOR 41823707.

References[edit]

- Hutchison, Jane Campbell (1993). Kristin L. Spangenberg (ed.). Six centuries of master prints : treasures from the Herbert Greer French collection. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum. ISBN 978-0-931537-15-8.

- Mayor, Alpheus Hyatt (1971). Prints & people; a social history of printed pictures. Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-00326-9.

- (Parshall): David Landau & Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- Shestack, Alan (1967). Fifteenth Century engravings of Northern Europe from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. LCCN 67029080.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, a book from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Israhel van Meckenem (see index)

- The Wild Man: Medieval Myth and Symbolism, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Ishrahel van Meckenem (see index)

- nine prints from the National Gallery of Art, Washington

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch