Kalevala

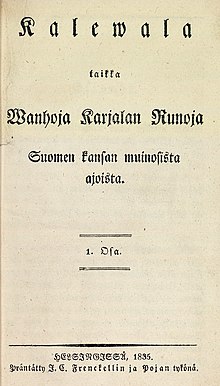

Kalevala. The Finnish national epic by Elias Lönnrot. First edition, 1835. | |

| Author | Elias Lönnrot |

|---|---|

| Original title | Kalevala (or Kalewala, first edition, 1835) |

| Translator | |

| Country | Grand Duchy of Finland |

| Language | Finnish |

| Genre | |

| Publisher | J. C. Frenckell ja Poika, among others |

Publication date |

|

Published in English |

|

| Pages |

|

| 894.5411 | |

| LC Class | PH324 .E5 |

Original text | Kalevala (or Kalewala, first edition, 1835) at Finnish Wikisource |

| Translation | Kalevala at Wikisource |

The Kalevala (IPA: [ˈkɑleʋɑlɑ]) is a 19th-century compilation of epic poetry, compiled by Elias Lönnrot from Karelian and Finnish oral folklore and mythology,[1] telling an epic story about the Creation of the Earth, describing the controversies and retaliatory voyages between the peoples of the land of Kalevala called Väinölä and the land of Pohjola and their various protagonists and antagonists, as well as the construction and robbery of the epic mythical wealth-making machine Sampo.[2]

The Kalevala is regarded as the national epic of Karelia and Finland[Note 1] and is one of the most significant works of Finnish literature with J. L. Runeberg's The Tales of Ensign Stål and Aleksis Kivi's The Seven Brothers.[4][5][6] The Kalevala was instrumental in the development of the Finnish national identity and the intensification of Finland's language strife that ultimately led to Finland's independence from Russia in 1917.[7][8] The work is known internationally and has partly influenced, for example, J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium (i.e. Middle-earth mythology).[9][10]

The first version of the Kalevala, called the Old Kalevala, was published in 1835, consisting of 12,078 verses. The version most commonly known today was first published in 1849 and consists of 22,795 verses, divided into fifty folk stories (Finnish: runot).[11] An abridged version, containing all fifty poems but just 9732 verses, was published in 1862.[12] In connection with the Kalevala, there is another much more lyrical collection of poems, also compiled by Lönnrot, called Kanteletar from 1840, which is mostly seen as a "sister collection" of the Kalevala.[13]

Collection and compilation[edit]

Elias Lönnrot[edit]

Elias Lönnrot (9 April 1802 – 19 March 1884) was a physician, botanist, linguist, and poet. During the time he was compiling the Kalevala he was the district health officer based in Kajaani responsible for the whole Kainuu region in the eastern part of what was then the Grand Duchy of Finland. He was the son of Fredrik Johan Lönnrot, a tailor and Ulrika Lönnrot; he was born in the village of Sammatti, Uusimaa.

At the age of 21, he entered the Imperial Academy of Turku and obtained a master's degree in 1826. His thesis was entitled De Vainamoine priscorum fennorum numine (Väinämöinen, a Divinity of the Ancient Finns). The monograph's second volume was destroyed in the Great Fire of Turku the same year.[14][15]

In the spring of 1828, he set out with the aim of collecting folk songs and poetry. Rather than continue this work, though, he decided to complete his studies and entered Imperial Alexander University in Helsinki to study medicine. He earned a master's degree in 1832. In January 1833, he started as the district health officer of Kainuu and began his work on collecting poetry and compiling the Kalevala. Throughout his career Lönnrot made a total of eleven field trips within a period of fifteen years.[16][17]

Prior to the publication of the Kalevala, Elias Lönnrot compiled several related works, including the three-part Kantele (1829–1831), the Old Kalevala (1835) and the Kanteletar (1840).

Lönnrot's field trips and endeavours helped him to compile the Kalevala, and brought considerable enjoyment to the people he visited; he would spend much time retelling what he had collected as well as learning new poems.[18][19]

Poetry[edit]

History[edit]

Before the 18th century, Kalevala poetry, also known as runic song was common throughout Finland and Karelia, but in the 18th century it began to disappear in Finland, first in western Finland, because European rhymed poetry became more common in Finland. Finnish folk poetry was first written down in the 17th century[20][21] and collected by hobbyists and scholars through the following centuries. Despite this, the majority of Finnish poetry remained only in the oral tradition.

Finnish born nationalist and linguist Carl Axel Gottlund (1796–1875) expressed his desire for a Finnish epic in a similar vein to the Iliad, Ossian and the Nibelungenlied compiled from the various poems and songs spread over most of Finland. He hoped that such an endeavour would incite a sense of nationality and independence in the native Finnish people.[22] In 1820, Reinhold von Becker founded the journal Turun Wiikko-Sanomat (Turku Weekly News) and published three articles entitled Väinämöisestä (Concerning Väinämöinen). These works were an inspiration for Elias Lönnrot in creating his masters thesis at Turku University.[14][23]

In the 19th century, collecting became more extensive, systematic and organised. Altogether, almost half a million pages of verse have been collected and archived by the Finnish Literature Society and other collectors in what are now Estonia and the Republic of Karelia.[24] The publication Suomen Kansan Vanhat Runot (Ancient Poems of the Finns) published 33 volumes containing 85,000 items of poetry over a period of 40 years. They have archived 65,000 items of poetry that remain unpublished.[25] By the end of the 19th century this pastime of collecting material relating to Karelia and the developing orientation towards eastern lands had become a fashion called Karelianism, a form of national romanticism.

The chronology of this oral tradition is uncertain. The oldest themes, the origin of Earth, have been interpreted to have their roots in distant, unrecorded history and could be as old as 3,000 years.[26] The newest events, e.g. the arrival of Christianity, seem to be from the Iron Age, which in Finland lasted until c. 1300 CE. Finnish folklorist Kaarle Krohn proposes that 20 of the 45 poems of the Kalevala are of possible Ancient Estonian origin or at least deal with a motif of Estonian origin (of the remainder, two are Ingrian and 23 are Western Finnish).[27]

It is understood that during the Finnish reformation in the 16th century the clergy forbade all telling and singing of pagan rites and stories. In conjunction with the arrival of European poetry and music this caused a significant reduction in the number of traditional folk songs and their singers. Thus the tradition faded somewhat but was never totally eradicated.[28]

Lönnrot's field trips[edit]

In total, Lönnrot made eleven field trips in search of poetry. His first trip was made in 1828 after his graduation from Turku University, but it was not until 1831 and his second field trip that the real work began. By that time he had already published three articles entitled Kantele and had significant notes to build upon. This second trip was not very successful and he was called back to Helsinki to attend to victims of the Second cholera pandemic.[29]

The third field trip was much more successful and led Elias Lönnrot to Viena in east Karelia where he visited the town of Akonlahti, which proved most successful. This trip yielded over 3,000 verses and copious notes.[30] In 1833, Lönnrot moved to Kajaani where he was to spend the next 20 years as the district health officer for the region, living in the Hövelö croft located near the Lake Oulujärvi in the Paltaniemi village, spending his spare time searching for poems.[31][32] His fourth field trip was undertaken in conjunction with his work as a doctor; a 10-day jaunt into Viena. This trip resulted in 49 poems and almost 3,000 new lines of verse. It was during this trip that Lönnrot formulated the idea that the poems might represent a wider continuity, when poem entities were performed to him along with comments in normal speech connecting them.[33][34]

On the fifth field trip, Lönnrot met Arhippa Perttunen who, over two days of continuous recitation, provided him with some 4,000 verses for the Kalevala. He also met a singer called Matiska in the hamlet of Lonkka on the Russian side of the border. Although this singer had a somewhat poor memory, he did help to fill in many gaps in the work Lönnrot had already catalogued. This trip resulted in the discovery of almost 300 poems at just over 13,000 verses.[35]

In autumn of 1834, Lönnrot had written the vast majority of the work needed for what was to become the Old Kalevala; all that was required was to tie up some narrative loose ends and complete the work. His sixth field trip took him into Kuhmo, a municipality in Kainuu to the south of Viena. There he collected over 4,000 verses and completed the first draft of his work. He wrote the foreword and published in February of the following year.[36]

With the Old Kalevala well into its first publication run, Lönnrot decided to continue collecting poems to supplement his existing work and to understand the culture more completely. The seventh field trip took him on a long winding path through the southern and eastern parts of the Viena poem singing region. He was delayed significantly in Kuhmo because of bad skiing conditions. By the end of that trip, Lönnrot had collected another 100 poems consisting of over 4,000 verses.[37] Lönnrot made his eighth field trip to the Russian border town of Lapukka where the great singer Arhippa Perttunen had learned his trade. In correspondence he notes that he has written down many new poems but is unclear on the quantity.[38]

Elias Lönnrot departed on the first part of his ninth field trip on 16 September 1836. He was granted a 14-month leave of absence and a sum of travelling expenses from the Finnish Literary Society. His funds came with some stipulations: he must travel around the Kainuu border regions and then on to the north and finally from Kainuu to the south-east along the border. For the expedition into the north he was accompanied by Juhana Fredrik Cajan. The first part of the trip took Lönnrot all the way to Inari in northern Lapland.[39] The second, southern part of the journey was more successful than the northern part, taking Lönnrot to the town of Sortavala on Lake Ladoga then back up through Savo and eventually back to Kajaani. Although these trips were long and arduous, they resulted in very little Kalevala material; only 1,000 verses were recovered from the southern half and an unknown quantity from the northern half.[40]

The tenth field trip is a relative unknown. What is known however, is that Lönnrot intended to gather poems and songs to compile into the upcoming work Kanteletar. He was accompanied by his friend C. H. Ståhlberg for the majority of the trip. During that journey the pair met Mateli Magdalena Kuivalatar in the small border town of Ilomantsi. Kuivalatar was very important to the development of the Kanteletar.[41] The eleventh documented field trip was another undertaken in conjunction with his medical work. During the first part of the trip, Lönnrot returned to Akonlahti in Russian Karelia, where he gathered 80 poems and a total of 800 verses. The rest of the trip suffers from poor documentation.[42]

Methodology[edit]

Lönnrot and his contemporaries, e.g. Matthias Castrén, Anders Johan Sjögren,[43] and David Emmanuel Daniel Europaeus[44][45] collected most of the poem variants; one poem could easily have countless variants, scattered across rural areas of Karelia and Ingria. Lönnrot was not really interested in, and rarely wrote down the name of the singer except for some of the more prolific cases. His primary purpose in the region was that of a physician and of an editor, not of a biographer or counsellor. He rarely knew anything in-depth about the singer himself and primarily only catalogued verse that could be relevant or of some use in his work.[46]

The student David Emmanuel Daniel Europaeus is credited with discovering and cataloguing the majority of the Kullervo story.[45][47][48]

Of the dozens of poem singers who contributed to the Kalevala, significant ones are:

- Arhippa Perttunen (1769–1840)

- Juhana Kainulainen

- Matiska

- Ontrei Malinen (1780–1855)

- Vaassila Kieleväinen

- Soava Trohkimainen

Form and structure[edit]

The poetry was often sung to music built on a pentachord, sometimes assisted by a kantele player. The rhythm could vary but the music was arranged in either two or four lines in 5

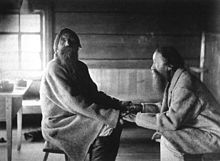

4 metre.[citation needed] The poems were often performed by a duo, each person singing alternative verses or groups of verses. This method of performance is called an antiphonic performance, it is a kind of "singing match".

Metre[edit]

Despite the vast geographical distance and customary spheres separating individual singers, the folk poetry the Kalevala is based on was always sung in the same metre.

The Kalevala's metre is a form of trochaic tetrameter that is now known as the Kalevala metre. The metre is thought to have originated during the Proto-Finnic period. Its syllables fall into three types: strong, weak, and neutral. Its main rules are as follows:[49][50]

- A long syllable (one that contains a long vowel or a diphthong, or ends in a consonant) with a main stress is metrically strong.

- In the second, third, and fourth foot of a line, a strong syllable can occur in only the rising part:

- Veli / kulta, / veikko/seni (1:11)

- ("Dearest friend, and much-loved brother"[51])

- The first foot has a freer structure, allowing strong syllables in a falling position as well as a rising one:

- Niit' en/nen i/soni / lauloi (1:37)

- ("These my father sang aforetime")

- A short syllable with a main stress is metrically weak.

- In the second, third, and fourth feet, a weak syllable can occur only in the falling part:

- Miele/ni mi/nun te/kevi (1:1)

- ("I am driven by my longing")

- Again, the first foot's structure is more free, allowing weak syllables in a rising position as well as a falling one:

- vesois/ta ve/tele/miä (1:56)

- ("Others taken from the saplings")

- All syllables without a main stress are metrically neutral. Neutral syllables can occur at any position.

There are two main types of line:[50]

- A normal tetrameter, word-stresses and foot-stresses match, and there is a caesura between the second and third feet:

- Veli / kulta, // veikko/seni

- A broken tetrameter (Finnish: murrelmasäe) has at least one stressed syllable in a falling position. There is usually no caesura:

- Miele/ni mi/nun te/kevi

Traditional poetry in the Kalevala metre uses both types with approximately the same frequency. The alternating normal and broken tetrameters is a characteristic difference between the Kalevala metre and other forms of trochaic tetrameter.

There are four additional rules:[50]

- In the first foot, the length of syllables is free. It is also possible for the first foot to contain three or even four syllables.

- A one-syllable word can not occur at the end of a line.

- A word with four syllables should not stand in the middle of a line. This also applies to non-compound words.

- The last syllable of a line may not include a long vowel.

Schemes[edit]

There are two main schemes featured in the Kalevala:[50]

- Alliteration can be broken into two forms. Weak: where only the opening consonant is the same, and strong: where both the first vowel or vowel and consonant are the same in the different words. (e.g. Finnish: vaka vanha Väinämöinen, lit. 'Steadfast old Väinämöinen').

- Parallelism in The Kalevala refers to the stylistic feature of repeating the idea presented in the previous line, often by using synonyms, rather than moving the plot forward. (e.g. Finnish: Näillä raukoilla rajoilla / Poloisilla pohjan mailla, lit. 'In these dismal Northern regions / In the dreary land of Pohja'). Lönnrot has been criticised for overusing parallelism in The Kalevala: in the original poems, a line was usually followed by only one such parallel line.[52]

The verses are sometimes inverted into chiasmus.

Poetry example[edit]

Verses 221 to 232 of song forty.[51][53]

Vaka vanha Väinämöinen | Väinämöinen, old and steadfast, |

Lönnrot's contribution to the Kalevala[edit]

Very little is actually known about Elias Lönnrot's personal contributions to the Kalevala. Scholars to this day still argue about how much of the Kalevala is genuine folk poetry and how much is Lönnrot's own work – and the degree to which the text is 'authentic' to the oral tradition.[54] During the compilation process it is known that he merged poem variants and characters together, left out verses that did not fit and composed lines of his own to connect certain passages into a logical plot. Similarly, as was normal in the preliterate conventions of oral poetry—according to the testimony of Arhippa Perttunen—traditional bards in his father's days would always vary the language of songs from performance to performance when reciting from their repertoire.[45][46][55][56]

The Finnish historian Väinö Kaukonen suggests that 3% of the Kalevala's lines are Lönnrot's own composition, 14% are Lönnrot compositions from variants, 50% are verses which Lönnrot kept mostly unchanged except for some minor alterations, and 33% are original unedited oral poetry.[57]

Publishing[edit]

Finnish language[edit]

The first version of Lönnrot's compilation was entitled Kalewala, taikka Wanhoja Karjalan Runoja Suomen Kansan muinoisista ajoista ("The Kalevala, or old Karelian poems about ancient times of the Finnish people"), also known as the Old Kalevala. It was published in two volumes in 1835–1836. The Old Kalevala consisted of 12,078 verses making up a total of thirty-two poems.[58][59]

Even after the publication of the Old Kalevala Lönnrot continued to collect new material for several years. He later integrated this additional material, with significantly edited existing material, into a second version, the Kalevala. This New Kalevala, published in 1849, contains fifty poems, with a number of plot differences compared with the first version, and is the standard text of the Kalevala read and translated to this day. (Published as: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia. 14 Osa. KALEVALA.)

The word Kalevala rarely appears in the original folk songs. The first appearance of the word in folk songs was recorded in April 1836.[60] Lönnrot chose it as the title for his project sometime at the end of 1834,[37][61] but his choice was not random. The name "Kalev" appears in Finnic and Baltic folklore in many locations, and the Sons of Kalev are known throughout Finnish and Estonian folklore.[27]

Lönnrot produced Lyhennetty laitos, an abridged version of the Kalevala, in 1862. It was intended for use in schools. It retains all 50 poems from the 1849 version, but omits more than half of the verses.

Translations[edit]

Of the few complete translations into English, it is only the older translations by John Martin Crawford (1888) and William Forsell Kirby (1907) which attempt to strictly follow the original (Kalevala metre) of the poems.[26][51]

A notable partial translation of Franz Anton Schiefner's German translation was made by Prof. John Addison Porter in 1868 and published by Leypoldt & Holt.[62]

Edward Taylor Fletcher, a British-born Canadian literature enthusiast, translated selections of the Kalevala in 1869. He read them before the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec on 17 March 1869.[63][64]

Francis Peabody Magoun published a scholarly translation of the Kalevala in 1963 written entirely in prose. The appendices of this version contain notes on the history of the poem, comparisons between the original Old Kalevala and the current version, and a detailed glossary of terms and names used in the poem.[65] Magoun translated the Old Kalevala, which was published six years later entitled The Old Kalevala and Certain Antecedents.

Eino Friberg's 1988 translation uses the original metre selectively but in general is more attuned to pleasing the ear than being an exact metrical translation; it also often reduces the length of songs for aesthetic reasons.[66] In the introduction to his 1989 translation,[67] Keith Bosley stated: "The only way I could devise of reflecting the vitality of Kalevala metre was to invent my own, based on syllables rather than feet. While translating over 17,000 lines of Finnish folk poetry before I started on the epic, I found that a line settled usually into seven syllables of English, often less, occasionally more. I eventually arrived at seven, five and nine syllables respectively, using the impair (odd number) as a formal device and letting the stresses fall where they would."[68]: l

Most recently, Finnish/Canadian author and translator Kaarina Brooks translated into English the complete runic versions of Old Kalevala 1835 (Wisteria Publications 2020) and Kalevala (Wisteria Publications 2021). These works, unlike some previous versions, faithfully follow the Kalevala meter (Trochaic tetrameter) throughout and can be sung or chanted as Elias Lönnrot had intended. Brooks says, "It is essential that the translation of Kalevala into any language follows the Kalevala metre, for that was how these runes were sung in times immemorial. So that readers get the full impact of these ancient runes, it is imperative that they be presented in the same chanting style." Kaarina Brooks is also the translator of, An Illustrated Kalevala Myths and Legends from Finland, published by Floris Books UK.[69][70]

Modern translations were published in the Karelian and Urdu languages between 2009 and 2015. Thus, the Kalevala was published in its originating Karelian language only after 168 years since its first translation into Swedish.[71]

As of 2010, the Kalevala had been translated into sixty-one languages and is Finland's most translated work of literature.[72][73]

The story[edit]

Introduction[edit]

The Kalevala begins with the traditional Finnish creation myth, leading into stories of the creation of the earth, plants, creatures, and the sky. Creation, healing, combat and internal story telling are often accomplished by the character(s) involved singing of their exploits or desires. Many parts of the stories involve a character hunting or requesting lyrics (spells) to acquire some skill, such as boatbuilding or the mastery of iron making. As well as magical spell casting and singing, there are many stories of lust, romance, kidnapping and seduction. The protagonists of the stories often have to accomplish feats that are unreasonable or impossible which they often fail to achieve, leading to tragedy and humiliation.

The Sampo is a pivotal element of the whole work. Many actions and their consequences are caused by the Sampo itself or a character's interaction with the Sampo. It is described as a magical talisman or device that brings its possessor great fortune and prosperity, but its precise nature has been the subject of debate to the present day.

Cantos[edit]

First Väinämöinen Cycle[edit]

Cantos 1 to 2: The poem begins with an introduction by the singers. The Earth is created from the shards of the egg of a goldeneye and the first man, Väinämöinen, is born to the goddess Ilmatar. Väinämöinen brings trees and life to the barren world.

Cantos 3–5: Väinämöinen encounters the jealous Joukahainen and they engage in a battle of song. Joukahainen loses and pledges his sister's hand in return for his life; the sister Aino soon drowns herself in the sea.

Cantos 6–10: Väinämöinen heads to Pohjola to propose to a maiden of the north, a daughter of the mistress of the north Louhi. Joukahainen attacks Väinämöinen again, and Väinämöinen floats for days on the sea until he is carried by an eagle to Pohjola. He makes a deal with Louhi to get Ilmarinen the smith to create the Sampo. Ilmarinen refuses to go to Pohjola so Väinämöinen forces him against his will. The Sampo is forged. Ilmarinen returns without a bride.

First Lemminkäinen Cycle[edit]

Cantos 11–15: Lemminkäinen sets out in search of a bride. He and the maid Kyllikki make vows but the happiness doesn't last long and Lemminkäinen sets off to woo a maiden of the north. His mother tries to stop him, but he disregards her warnings and instead gives her his hairbrush, telling her that if it starts to bleed he has met his doom. At Pohjola Louhi assigns dangerous tasks to him in exchange for her daughter's hand. While hunting for the swan of Tuonela, Lemminkäinen is killed and falls into the river of death. The brush he gave to his mother begins to bleed. Remembering her son's words, she goes in search of him. With a rake given to her by Ilmarinen, she collects the pieces of Lemminkäinen scattered in the river and pieces him back together.

Second Väinämöinen Cycle[edit]

Cantos 16–18: Väinämöinen builds a boat to travel to Pohjola once again in search of a bride. He visits Tuonela and is held prisoner, but he manages to escape and sets out to gain knowledge of the necessary spells from the giant Antero Vipunen. Väinämöinen is swallowed and has to torture Antero Vipunen for the spells and his escape. With his boat completed, Väinämöinen sets sail for Pohjola. Ilmarinen learns of this and resolves to go to Pohjola himself to woo the maiden. The maiden of the north chooses Ilmarinen.

Ilmarinen's Wedding[edit]

Cantos 19–25: Ilmarinen is assigned dangerous unreasonable tasks to win the hand of the maiden. He accomplishes these tasks with some help from the maiden herself. In preparation for the wedding, beer is brewed, a giant steer is slaughtered, and invitations are sent out. Lemminkäinen is uninvited. The wedding party begins and all are happy. Väinämöinen sings and lauds the people of Pohjola. The bride and bridegroom are prepared for their roles in matrimony. The couple arrive home and are greeted with drink and viands.

Second Lemminkäinen Cycle[edit]

Cantos 26–30: Lemminkäinen is resentful for not having been invited to the wedding and sets out immediately for Pohjola. On his arrival he is challenged to and wins a duel with Sariola, the Master of the North. Louhi is enraged and an army is conjured to enact revenge upon Lemminkäinen. He flees to his mother, who advises him to head to Saari, the Island of Refuge. On his return he finds his house burned to the ground. He goes to Pohjola with his companion Tiera to exact his revenge, but Louhi freezes the seas and Lemminkäinen has to return home. When he arrives home he is reunited with his mother and vows to build larger better houses to replace the ones burned down.

Kullervo Cycle[edit]

Cantos 31–36: Untamo kills his brother Kalervo's people, but spares his wife who later conceives Kullervo. Untamo sees the boy as a threat, and after trying to have him killed several times without success, sells Kullervo as a slave to Ilmarinen. Ilmarinen's wife torments and bullies Kullervo, so he tricks her into being torn apart by a pack of wolves and bears. Kullervo escapes from Ilmarinen's homestead and learns from an old lady in the forest that his family is still alive, and is soon reunited with them. While returning home from paying taxes, he meets and seduces a young maiden, only to find out that she is his sister. Upon realizing this, she kills herself and Kullervo returns home distressed. He decides to wreak revenge upon Untamo and sets out to find him. Kullervo wages war on Untamo and his people, laying all to waste, and then returns home, where he finds his farm deserted. Filled with remorse and regret, he kills himself in the place where he seduced his sister.

Second Ilmarinen Cycle[edit]

Cantos 37–38: Grieving for his lost love, Ilmarinen forges himself a wife out of gold and silver, but finds her to be cold and discards her. He heads for Pohjola and kidnaps the youngest daughter of Louhi. The daughter insults him so badly that he instead sings a spell to turn her into a bird and returns to Kalevala without her. He tells Väinämöinen about the prosperity and wealth that has met Pohjola's people thanks to the Sampo.

Theft of the Sampo[edit]

Cantos 39–44: Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen and Lemminkäinen sail to Pohjola to recover the Sampo. While on their journey they kill a monstrous pike and from its jaw bone the first kantele is made, with which Väinämöinen sings so beautifully even deities gather to listen. The heroes arrive in Pohjola and demand a share of the Sampo's wealth or they will take the whole Sampo by force. Louhi musters her army; however, Väinämöinen lulls everyone in Pohjola to sleep with his music. The Sampo is taken from its vault of stone and the heroes set out for home. Louhi conjures a great army, turns herself into a massive eagle and fights for the Sampo. In the battle the Sampo is lost to the sea and destroyed.

Louhi's Revenge on Kalevala[edit]

Cantos 45–49: Enraged at the loss of the Sampo, Louhi sends the people of Kalevala diseases and a great bear to kill their cattle. She hides the sun and the moon and steals fire from Kalevala. Väinämöinen heals all of the ailments and, with Ilmarinen, restores the fire. Väinämöinen forces Louhi to return the Sun and the Moon to the skies.

Marjatta cycle[edit]

Canto 50: The shy young virgin Marjatta becomes impregnated from a lingonberry she ate while tending to her flock. She conceives a son. Väinämöinen orders the killing of the boy, but the boy begins to speak and reproaches Väinämöinen for ill judgement. The child is then baptised King of Karelia. Väinämöinen sails away leaving only his songs and kantele as legacy but vowing to return when there's no moon or sun and happiness isn't free anymore.

The poem ends and the singers sing a farewell and thank their audience.

Characters[edit]

Väinämöinen[edit]

Väinämöinen, the central character of The Kalevala, is a shamanistic hero with a magical power of song and music similar to that of Orpheus. He is born of Ilmatar and contributes to the creation of Earth as it is today. Many of his travels resemble shamanistic journeys, most notably one where he visits the belly of a ground-giant, Antero Vipunen, to find the songs of boat building. Väinämöinen's search for a wife is a central element in many stories, but he never finds one.

Väinämöinen is associated with playing a kantele, a Finnish stringed instrument that resembles and is played like a zither.[74][75]

Ilmarinen[edit]

Seppo Ilmarinen is a heroic artificer (comparable to the Germanic Weyland and the Greek Daedalus). He crafted the dome of the sky, the Sampo and various other magical devices featured in The Kalevala. Ilmarinen, like Väinämöinen, also has many stories told of his search for a wife, reaching the point where he forges one of gold.

Lemminkäinen[edit]

Lemminkäinen, a handsome, arrogant and reckless seducer, is the son of Lempi (Finnish for 'lust' / 'favourite'). He has a close relationship with his mother, who revives him after he has been drowned in the river of Tuonela while pursuing the object of his romantic desires.

Ukko[edit]

Ukko (Finnish for 'Old man') is the god of sky and thunder, and the leading deity mentioned within The Kalevala. He corresponds to Thor and Zeus.

Joukahainen[edit]

Joukahainen is a base young man who arrogantly challenges Väinämöinen to a singing contest, which he loses. In exchange for his life Joukahainen promises his young sister Aino to Väinämöinen. Joukahainen attempts to gain his revenge on Väinämöinen by killing him with a crossbow, but only succeeds in killing Väinämöinen's horse. Joukahainen's actions lead to Väinämöinen promising to build a Sampo in return for Louhi rescuing him.

Louhi[edit]

Louhi, the Mistress of the North, is the shamanistic matriarch of the people of Pohjola, a people rivalling those of Kalevala. She is the cause of much trouble for Kalevala and its people.

Louhi at one point saves Väinämöinen's life. She has many daughters whom the heroes of Kalevala make many attempts, some successful, to seduce. Louhi plays a major part in the battle to prevent the heroes of Kalevala from stealing back the Sampo, which as a result is ultimately destroyed. She is a powerful witch with a skill almost on a par with that of Väinämöinen.

Kullervo[edit]

Kullervo is the vengeful, mentally ill, tragic son of Kalervo. He was abused as a child and sold into slavery to Ilmarinen. He is put to work and treated badly by Ilmarinen's wife, whom he later kills. Kullervo is a misguided and troubled youth, at odds with himself and his situation. He often goes into berserk rage, and in the end commits suicide.

Marjatta[edit]

Marjatta is a young virgin of Kalevala. She becomes pregnant from eating a lingonberry. When her labour begins she is expelled from her parents' home and leaves to find a place where she can sauna and give birth. She is turned away from numerous places but finally finds a place in the forest and gives birth to a son. Marjatta's nature, impregnation and searching for a place to give birth are in allegory to the Virgin Mary and the Christianisation of Finland.[76] Marjatta's son is later condemned to death by Väinämöinen for being born out of wedlock. The boy in turn chastises Väinämöinen and is later crowned King of Karelia. This angers Väinämöinen, who leaves Kalevala after bequeathing his songs and kantele to the people as his legacy.

Influence[edit]

The Kalevala is a major part of Finnish culture and history. It has influenced the arts in Finland and in other cultures around the world.[citation needed] In 2024, the European Commission granted the epic with a European Heritage Label.[77]

Finnish daily life[edit]

The influence of the Kalevala in daily life and business in Finland is tangible. Names and places associated with the Kalevala have been adopted as company and brand names and as place names.

There are several places within Finland with Kalevala-related names, for example: the district of Tapiola in the city of Espoo; the district of Pohjola in the city of Turku, the district of Metsola in the city of Vantaa, and the districts of Kaleva and Sampo in the city of Tampere; the historic provinces of Savo and Karjala and the Russian town of Hiitola are all mentioned within the songs of the Kalevala. In addition, the Russian town of Ukhta was in 1963 renamed Kalevala. In the United States a small community founded in 1900 by Finnish immigrants is named Kaleva, Michigan; many of the street names are taken from the Kalevala.

The banking sector of Finland has had at least three Kalevala-related brands: Sampo Bank (name changed to Danske Bank in late 2012), OP-Pohjola Group and Tapiola Bank.

The jewellery company Kalevala Koru was founded in 1935 on the 100th anniversary of the publication of the Old Kalevala. It specialises in the production of unique and culturally important items of jewellery. It is co-owned by the Kalevala Women's League and offers artistic scholarships to a certain number of organisations and individuals every year.[78]

The Finnish dairy company Valio has a brand of ice-cream named Aino, specialising in more exotic flavours than their normal brand.[79]

The construction group Lemminkäinen was formed in 1910 as a roofing and asphalt company. The name was chosen specifically to emphasise that they were a wholly Finnish company. They now operate internationally.[80][81]

Finnish calendar[edit]

Kalevala Day is celebrated in Finland on 28 February, to celebrate the publication date of Elias Lönnrot's first version of the Kalevala in 1835.[82] By its other official name, the day is known as the Finnish Culture Day.[83]

Several of the names in the Kalevala are celebrated as Finnish name days. The name days themselves and the dates they fall upon have no direct relationship with the Kalevala itself; however, the adoption of the names became commonplace after the release of the Kalevala.[84]

Art[edit]

Several artists have been influenced by the Kalevala, most notably Akseli Gallen-Kallela.[85]

Iittala group's Arabia brand kilned a series of Kalevala commemorative plates, designed by Raija Uosikkinen (1923–2004). The series ran from 1976 to 1999, and the plates are highly sought-after collectibles.[86][87]

One of the earliest artists to depict the Kalevala was Robert Wilhelm Ekman.[88]

In 1989, the fourth full translation of the Kalevala into English was published, illustrated by Björn Landström.[89]

Literature[edit]

The Kalevala has been translated over 150 times, into over 60 different languages.[90] (See § translations.)

Re-tellings[edit]

Finnish cartoonist Kristian Huitula illustrated a comic book adaptation of the Kalevala. The Kalevala Graphic Novel contains the storyline of all the 50 chapters in original text form.[91]

Finnish cartoonist and children's writer Mauri Kunnas wrote and illustrated Koirien Kalevala (Finnish for 'The Canine Kalevala'). The story is that of the Kalevala, with the characters presented as anthropomorphised dogs, wolves and cats. The story deviates from the full Kalevala to make the story more appropriate for children.[92]

In the late 1950s, students from the Rose Bruford College of Speech and Drama performed excerpts from the Kalevala in a presentation to the poet laureate John Masefield at Oxford. Some images from this presentation can be viewed online

The Kalevala inspired the American Disney cartoonist Don Rosa to draw a Donald Duck (who is himself a popular character in Finland) story based on the Kalevala, called The Quest for Kalevala.[93] The comic was released on the 150th anniversary of the Kalevala.[94]

Works inspired by[edit]

Franz Anton Schiefner's translation of the Kalevala was one inspiration for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1855 poem The Song of Hiawatha, which is written in a similar trochaic tetrameter.[95][96]

Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald's Estonian national epic Kalevipoeg was inspired by the Kalevala. Both Väinämöinen and Ilmarinen are mentioned in the work, and the overall story of Kalevipoeg, Kalev's son, bears similarities to the Kullervo story.[97]

J. R. R. Tolkien claimed the Kalevala as one of his sources for The Silmarillion. For example, the tale of Kullervo is the basis of Túrin Turambar in Narn i Chîn Húrin, including the sword that speaks when the anti-hero uses it to commit suicide.[10] Aulë, the Lord of Matter and the Master of All Crafts, was influenced by Ilmarinen, the Eternal Hammerer.[98] Echoes of the Kalevala's characters, Väinämöinen in particular, can be found in Tom Bombadil of The Lord of the Rings.[98][99][100]

Poet and playwright Paavo Haavikko took influence from the Kalevala, including in his poem Kaksikymmentä ja yksi (1974), and the TV drama Rauta-aika (1982).[101][102]

American science fiction and fantasy authors L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt used the Kalevala as source materials for their 1953 fantasy novella "The Wall of Serpents". This is the fourth story in the authors' Harold Shea series, in which the hero and his companions visit various mythic and fictional worlds. In this story, the characters visit the world of the Kalevala, where they encounter characters from the epic, drawn with a skeptical eye.

Emil Petaja was an American science fiction and fantasy author of Finnish descent. His best known works, known as the Otava Series, were a series of novels based on the Kalevala. The series brought Petaja readers from around the world, while his mythological approach to science fiction was discussed in scholarly papers presented at academic conferences.[103] He has a further Kalevala based work which is not part of the series, entitled The Time Twister.

British fantasy author Michael Moorcock's sword and sorcery anti-hero, Elric of Melniboné was influenced by the character Kullervo.[104]

British fantasy author Michael Scott Rohan's Winter of the World series feature Louhi as a major antagonist and include many narrative threads from the Kalevela.

The web comic "A Redtail's Dream", written and illustrated by Minna Sundberg, cites the Kalevala as an influence.[105] (Physical edition 2014.[106])

The British science fiction writer Ian Watson's Books of Mana duology, Lucky's Harvest and The Fallen Moon, both contain references to places and names from the Kalevala.[107]

In 2008, Vietnamese author and translator Bùi Viêt Hoa[108] published a piece of epic poetry The Children of Mon and Man (Vietnamese: Con cháu Mon Mân),[109] which delves into Vietnamese folk poetry and mythology, but was partially influenced by the Kalevala.[110] The work was written mainly in Finland[111] and the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs co-financed it.[110][112]

Music[edit]

Finnish music has been greatly influenced by the Kalevala, following in the tradition of the original song-poems.[113]

Classical music[edit]

The first recorded example of a musician influenced by the Kalevala is Filip von Schantz. In 1860, he composed the Kullervo Overture. The piece premièred at the opening of a new theatre in Helsinki on November of the same year. Von Schantz's work was followed by Robert Kajanus' Kullervo's Funeral March and the symphonic poem Aino in 1880 and 1885, respectively. Aino is credited with inspiring Jean Sibelius to investigate the richness of the Kalevala.[114] Die Kalewainen in Pochjola, the first opera freely based upon the Kalevala, was composed by Karl Müller-Berghaus in 1890.[115]

Jean Sibelius is the best-known Kalevala-influenced classical composer. Twelve of Sibelius' best-known works are based upon or influenced by the Kalevala, including his Kullervo, a tone poem for soprano, baritone, chorus and orchestra composed in 1892.[116] Sibelius also composed the music of Jääkärimarssi (Finnish for 'The Jäger March') to words written by Finnish soldier and writer Heikki Nurmio. The march features the line Me nousemme kostona Kullervon (Finnish for 'We shall rise in vengeance like that of Kullervo's').[117]

Other classical composers influenced by the Kalevala:

- Einojuhani Rautavaara[118]

- Leevi Madetoja[119]

- Uuno Klami[120]

- Tauno Marttinen[113][121]

- Aulis Sallinen[122]

- Veljo Tormis[123]

Folk metal[edit]

A number of folk metal bands have drawn on the Kalevala heavily for inspiration. In 1993, the Finnish bands Amorphis and Sentenced released two concept albums, Tales from the Thousand Lakes and North from Here respectively, which were the first of many Kalevala-inspired albums that have followed since. Amorphis's 2009 album Skyforger also draws heavily on the Kalevala.[124][125] The Finnish folk metal band Ensiferum have released songs such as "Old Man" and "Little Dreamer", which are influenced by the Kalevala. The third track of their Dragonheads EP, entitled "Kalevala Melody", is an instrumental piece following the rhythm of the Kalevala metre.[126][127] Another Finnish folk metal band, Turisas, have adapted several verses from song nine of the Kalevala, "The Origin of Iron", for the lyrics of their song "Cursed Be Iron", which is the third track of the album The Varangian Way.[128] Finnish metal band Amberian Dawn use lyrics inspired by the Kalevala on their album River of Tuoni, as well as on its successor, The Clouds of Northland Thunder.[129] On 3 August 2012, Finnish folk metal band Korpiklaani released a new album entitled Manala. Jonne Järvelä from the band said, "Manala is the realm of the dead – the underworld in Finnish mythology. Tuonela, Tuoni, Manala and Mana are used synonymously. This place is best known for its appearance in the Finnish national epic Kalevala, on which many of our new songs are based."[citation needed]

Other musical genres[edit]

In the mid-1960s, the progressive rock band Kalevala was active within Finland and in 1974, the now prolific singer-songwriter Jukka Kuoppamäki released the song "Väinämöinen". These were some of the first pieces of modern popular music inspired by the Kalevala.

In 1998, Ruth MacKenzie recorded the album Kalevala: Dream of the Salmon Maiden, a song cycle covering the story of Aino and her choice to refuse the hand of the sorcerer Väinämöinen, instead transforming herself into a salmon. MacKenzie has continued to perform the piece live.

The Karelian Finnish folk music group Värttinä has based some of its lyrics on motifs from the Kalevala.[130] The Vantaa Chamber Choir have songs influenced by the Kalevala. Their Kalevala-themed third album, Marian virsi (2005), combines contemporary folk with traditionally performed folk poetry.[131]

In 2003, the Finnish progressive rock quarterly Colossus and French Musea Records commissioned 30 progressive rock groups from around the world to compose songs based on parts of the Kalevala. The publication assigned each band with a particular song from the Kalevala, which the band was free to interpret as they saw fit. The result, titled Kalevala, is a three-disc, multilingual, four-hour epic telling.

In the beginning of 2009, in celebration of the 160th anniversary of the Kalevala's first published edition, the Finnish Literature Society, the Kalevala Society, premièred ten new and original works inspired by the Kalevala. The works included poems, classical and contemporary music and artwork. A book was published by the Finnish Literature Society in conjunction with the event and a large exhibition of Kalevala-themed artwork and cultural artefacts was put on display at the Ateneum museum in Helsinki.[132]

In 2017, a New York-based production Kalevala the Musical premiered in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Republic of Finland. The production featured original pop, folk and world music score written by Johanna Telander. The concert version was performed across the United States and Finland.[133]

Film and television[edit]

In 1959, a joint Finnish-Soviet production entitled Sampo, also known as The Day the Earth Froze, was released, inspired by the story of the Sampo from the Kalevala, which is also featured in a 1993 episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000.[134]

In 1982, the Finnish Broadcasting Company (YLE) produced a television mini-series called Rauta-aika (Finnish for 'The Age of Iron'), with music composed by Aulis Sallinen and book by Paavo Haavikko. The series was set "during the Kalevala times" and based upon events which take place in the Kalevala.[135][136] The series' part 3/4 won Prix Italia in 1983.

The martial arts film Jadesoturi, also known as Jade Warrior, released in Finland on 13 October 2006, was based upon the Kalevala and set in Finland and China.[137] Also, the 2013 film Kalevala: The New Era, directed by Jari Halonen, takes place both in the ancient land of the Kalevala and also in modern Finland. The film, made with a budget of €250,000, turned out to be a box-office bomb and received a mostly negative reception from critics.[138]

In "Chapter 17: The Apostate", the first episode of the third season of The Mandalorian series, Din Djarin meets with Bo-Katan in an old Mandalorian castle, which is located in the Mandalore system planet called Kalevala.[139][140] The same planet has also previously been mentioned in The Clone Wars series.[140]

Interpretations[edit]

The Kalevala has attracted many scholars and enthusiasts to interpret its contents in a historical context. Many interpretations of the themes have been tabled. Some parts of the epic have been perceived as ancient conflicts between the early Finns and the Sami. In this context, the country of "Kalevala" could be understood as Southern Finland and Pohjola as Lapland.[142]

However, the place names in Kalevala seem to transfer the Kalevala further south, which has been interpreted as reflecting the Finnic expansion from the South that came to push the Sami further to the north.[citation needed][Note 2] Some scholars locate the lands of Kalevala in East Karelia, where most of the Kalevala stories were written down. In 1961[contradictory], the small town of Uhtua in the then Soviet Republic of Karelia was renamed Kalevala, perhaps to promote that theory.

Finnish politician and linguist Eemil Nestor Setälä rejected the idea that the heroes of Kalevala are historical in nature and suggested they are personifications of natural phenomena. He interprets Pohjola as the northern heavens and the Sampo as the pillar of the world. Setälä suggests that the journey to regain the Sampo is a purely imaginary one with the heroes riding a mythological boat or magical steed to the heavens.[14][144][145]

The practice of bear worship was once very common in Finland and there are strong echoes of this in the Kalevala.[26]

The old Finnish word väinä (a strait of deep water with a slow current) appears to be the origin of the name Väinämöinen; one of Väinämöinen's other names is Suvantolainen, suvanto being the modern word for väinä. Consequently, it is possible that the Saari (Finnish for 'island') might be the island of Saaremaa in Estonia and Kalevala the Estonian mainland.[61]

Finnish folklorists Matti Kuusi and Pertti Anttonen state that terms such as the people of Kalevala or the tribe of Kalevala were fabricated by Elias Lönnrot. Moreover, they contend that the word Kalevala is very rare in traditional poetry and that by emphasizing dualism (Kalevala vs. Pohjola) Elias Lönnrot created the required tension that made the Kalevala dramatically successful and thus fit for a national epic of the time.[61]

There are similarities with mythology and folklore from other cultures, for example, the Kullervo character and his story bearing some likeness to the Greek Oedipus. The similarity of the virginal maiden Marjatta to the Christian Virgin Mary is striking. The arrival of Marjatta's son in the final song spelling the end of Väinämöinen's reign over Kalevala is similar to the arrival of Christianity bringing about the end of Paganism in Finland and Europe at large.[146]

See also[edit]

- Finnish mythology

- Mythologia Fennica

- Finnish national symbols

- Kalevi (mythology)

- Kalevipoeg, an Estonian epic poetry inspired by the Kalevala

- Kanteletar, a sister collection of the Kalevala

- Kojiki, a mythological text similarly compiled and edited from oral transmission

Notes[edit]

- ^ Professor Tolkien disagreed with this characterization: "One repeatedly hears the 'Land of Heroes' described as the 'national Finnish Epic': as if a nation, besides if possible a national bank theatre and government, ought also automatically to possess a national epic. Finland does not. The K[alevala] is certainly not one. It is a mass of conceivably epic material; but, and I think this is the main point, it would lose nearly all that which is its greatest delight if it were ever to be epically handled."[3]

- ^ It may be noted that place-names and other evidence show that in the medieval period, the Sami lived much further south than in the modern age, well south of Lapland, and place-names of Sami origin are not only found all over White Karelia, but as far as the Svir River basin and Nyland. Finnic peoples, on the other hand, were in antiquity, in the Iron Age, probably originally limited to the coasts south of the Gulf of Finland, in what is now Estonia, and no further north than the Karelian Isthmus.[143] In view of this, the possibility of identifying Pohjola with Finland/Karelia and Kalevala with Estonia (see further below on the location of the Saari) suggests itself.

References[edit]

- ^ Asplund, Anneli; Sirkka-Liisa Mettom (October 2000). "Kalevala: the Finnish national epic". Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ^ Kalevala, the national epic of Finland – Finnwards

- ^ Tolkien, J.R.R. (2015). "On 'The Kalevala' or Land of Heroes". In Flieger, Verlyn (ed.). The Story of Kullervo (1st US ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-544-70626-2.

- ^ Kansalliskirjailija on kansakunnan peili (in Finnish)

- ^ Tosi ja taru Vänrikki Stoolin tarinoissa (in Finnish)

- ^ Suomalaiset klassikkokirjat – Oletko lukenut näitä 10 kirjaa? (in Finnish)

- ^ Vento, Urpo. "The Role of The Kalevala" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ William A. Wilson (1975) "The Kalevala and Finnish Politics" Journal of the Folklore Institute 12(2/3): pp. 131–55

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-31555-7.

- ^ a b Sander, Hannah (27 August 2015). "Kullervo: Tolkien's fascination with Finland". BBC News. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ Kalevala Society. "Kalevala, the national epic". Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg EBook of Kalevala (1862)". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 6 December 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bosley, Keith (March 2000). "Finland's Other Epic: The Kanteletar". thisisFINLAND. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr. "The Kalevala or Poems of the Kaleva district" Appendix I. (1963).

- ^ Tuula Korolainen & Riitta Tulusto. "Monena mies eläessänsä – Elias Lönnrotin rooleja ja elämänvaiheita". Helsinki: Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö (2002)

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu". Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Elias Lönnrot". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 21 December 2013.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Kalevala poetry society (Finnish) Archived 7 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine, Finnish Literature Society (Finnish) Archived 24 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, "Where was The Kalevala born?" Finnish Literature Society, Helsinki, 1978. Accessed 17 August 2010

- ^ "SKVR XI. 866. Pohjanmaa. Pentzin, Virittäjä s. 231. 1928. Pohjal. taikoja ja loitsuja 1600-luvulta. -?". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ Gottlund, Carl Axel (21 June 1817), "Review", Svensk literatur-tidning, vol. 25, Stockholm, p. 394

- ^ "Turun Wiikko-Sanomat 1820 archive". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "The folklore activities of the Finnish Literature Society". Archived from the original on 17 May 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Suomen Kansan Vanhat Runot kotisivu". Archived from the original on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ a b c John Martin Crawford. Kalevala – The national epic of Finland, "Preface to the First edition, (1888)".

- ^ a b Eduard, Laugaste (1990). "The Kalevela and the Kalevipoeg". In Lauri Honko (ed.). Religion, Myth and Folklore in the World's Epics: The Kalevala and its Predecessors. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 265–286. ISBN 978-3-11-087455-6.

- ^ "Laulut Kalevalan takana". Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 2". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 3". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ Piippo, Esko (28 February 2021). "Näkökulma: Elias Lönnrotin Hövelön aika". Kainuun Sanomat (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Suutari, Tiina (16 March 2021). "Kotiseutuna Kajaani: Maanjäristys tuhosi ensimmäisen kirkon Paltaniemellä – Kirkkoaholla on toiminut erikoinen eläintarha". Kainuun Sanomat (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 4". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ "Letter to J L Runeberg". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 5". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 6". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 7". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 8". Archived from the original on 28 May 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 9 North". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 9 South". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 11". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ "Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu – Field trip 11". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr. "The Kalevala or Poems of the Kaleva district" Appendix II. (1963).

- ^ "Kansalliset symbolit ja juhlat – Kalevala". Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Elias Lönnrot. "Kalevala" Preface to the First edition, (1849).

- ^ a b Honko, Lauri (1990). "The Kalevela: The Processual View". In Lauri Honko (ed.). Religion, Myth and Folklore in the World's Epics: The Kalevala and its Predecessors. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 181–230. ISBN 978-3-11-087455-6.

- ^ Alhoniemi, Pirkko (1990). "The Reception of the Kalevela and Its Impact on the Arts". In Lauri Honko (ed.). Religion, Myth and Folklore in the World's Epics: The Kalevala and its Predecessors. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 231–246. ISBN 978-3-11-087455-6.

- ^ "Kansalliset symbolit ja juhlat". Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ Matti Kuusi; Keith Bosley; Michael Branch, eds. (1977). Finnish Folk Poetry: Epic: An Anthology in Finnish and English. Finnish Literature Society. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-951-717-087-1.

- ^ a b c d "Kalevalan runomitta". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Kalevala: The Land of Heroes, trans. by W. F. Kirby, 2 vols (London: Dent, 1907).

- ^ "Kalevalainen kerto eli parallellismi". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Elias Lönnrot, ed. (1849). The Kalevala.

- ^ Pertti, Anttonen (2014). "The Kalevala and the Authenticity Debate". In Bak, János M.; Geary, Patrick J.; Klaniczay, Gábor (eds.). Manufacturing a Past for the Present: Forgery and Authenticity in Medievalist Texts and Objects in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Brill. pp. 56–80. ISBN 9789004276802.

- ^ John Miles Foley, A companion to ancient epic, 2005, p.207.

- ^ Thomas DuBois. "From Maria to Marjatta: The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot's Kalevala" Oral Tradition, 8/2 (1993) pp.247–288

- ^ Väinö Kaukonen. "Lönnrot ja Kalevala" Finnish Literature Society, (1979).

- ^ "Doria.fi archive of the Old Kalevala volume 1". Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ "Doria.fi archive of the Old Kalevala volume 2". Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ "SKVR I2. 1158. Lönnrot Mehil. 1836, huhtik". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Matti Kuusi and Pertti Anttonen. "Kalevala Lipas" Finnish Literary Society, 1985.

- ^ "The Kalevala or National epos of the Finns". Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ Fletcher, E. T. Esq. "The Kalevala, or National Epos of the Finns." Transactions of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec NS 6 (1869): 45–68.

- ^ "The Kalevala or National epos of the Finns". Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Finland's folk epic". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Eino Friberg. Kalevala – Epic of the Finnish people, Introduction to the first edition, 1989.

- ^ The Kalevala – Reviews and Awards. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press. 9 October 2008. ISBN 978-0-19-953886-7. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Lönnrot, Elias (1989). "Introduction". The Kalevala. Translated by Bosley, Keith. Oxford / New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953886-7.

- ^ Celebration of Finnish Independence – Featured Lives – postponed – Canadian Friend of Finland

- ^ Kalevalainen nainen maailmalla – Kalevalaisten Naisten Liitto (in Finnish)

- ^ "Kalevalan käännökset | Kalevalaseura". Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "The Kalevala in translation". Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "National epic "The Kalevala" reaches the respectable age of 175". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "Matkoja musiikkiin 1800-luvun Suomessa (Journeys into music in 19th century Finland)". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "The Kantele Sings in Finnland – A Cultural Phenomenon". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, Part 14, by James Hastings, p. 642).

- ^ "Finnish epic Kalevala receives European Heritage Label". Yle. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Kalevala Koru Oy – Company information". Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Aino Jäätelö – product page". Archived from the original on 10 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Lemminkäinen Oyj – Company information". Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Early 1950s informational video (Finnish)". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Kalevala Society. "Kalevala Society Homepage". Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ^ thisisFINLAND. "The Finnish flag". Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ^ Saarelma, Minna. "Kalevalan nimet suomalaisessa nimipäiväkalenterissa – pp31-36(58–68)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ "Myth, magic and the museum". Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ^ "UOSIKKINEN, RAIJA". Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Arabia history, text in English" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Ekman, Robert Wilhelm". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Björn Landström". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010.

- ^ "The Kalevala in translation". Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ "The Art of Huitula – The Kalevala Comic Book (The Kalevala Graphic Novel)". Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Mauri Kunnas, The Canine Kalevala – (Koirien Kalevala)". Archived from the original on 7 November 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ "Don Rosa and The Quest for Kalevala". Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ "Don Rosan Kalevala-ankat". Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004: 108. ISBN 0-8070-7026-2.

- ^ Irmscher, Christoph. Longfellow Redux. University of Illinois, 2006: 108. ISBN 978-0-252-03063-5.

- ^ "Finnish Kalevala and Estonian Kalevipoeg". Archived from the original on 20 November 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ a b Mankkinen, Jussi (16 September 2022). "Taru sormusten herrasta on juuriltaan suomalaisempi kuin aiemmin on tiedetty – Tolkienilta löytyy vastineet Kullervolle, Sammolle ja Väinämöiselle" [The Lord of the Rings has more Finnish roots than previously known – Tolkien has equivalents for Kullervo, Sampo and Väinämöinen]. Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ Petty, Anne C. (2004). "Identifying England's Lönnrot" (PDF). Tolkien Studies. 1: 78–81. doi:10.1353/tks.2004.0014. S2CID 51680664. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2015.

- ^ Himes, Jonathan B. (Spring 2000), "What Tolkien Really Did with the Sampo", Mythlore, 22.4 (86): 69–85

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Paavo Haavikko". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010.

- ^ "Haavikko, Paavo (1931–2008)". Archived from the original on 15 July 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ Kailo, Kaarina. "Spanning the Iron and Space Ages: Emil Petaja's Kalevala-based fantasy tales" Kanadan Suomalainen, Toronto, Canada: Spring, 1985..

- ^ "Elric of Melniboné Archive – Moorcock's website forum archive". Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ "A Redtail's Dream (minnasundberg.fi)". Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Minna Sundberg, A Redtails dream, ISBN 978-91-637-4627-7

- ^ "Kuinka ryöstin Sammon". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ "Bui Viet Hoa". The Kalevala Society (Kalevalaseura). Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "The Children of Mon and Man" (PDF) (in Vietnamese). Juminkeko. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Vietnam sai oman Kalevalansa Suomen avulla". YLE (in Finnish). 1 March 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Vietnamin eepos: Tausta" (in Finnish). Juminkeko. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Vietnamin eepos: Monin ja Manin lapset" (in Finnish). Juminkeko. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Kalevalan Kultuurihistoria – Kalevala taiteessa – Musiikissa". Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Ensimmäiset Kalevala-aiheiset sävellykset". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Die Kalewainen in Pochjola: 127 vuotta kadoksissa ollut ooppera ensi-iltaan Turussa Suomi 100 -juhlavuonna. Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine City of Turku, 29 February 2016. (in Finnish)

- ^ "Jean Sibelius ja Kalevala". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Suomelle – isänmaallisia lauluja". Archived from the original on 4 November 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "SUOMALAISTA KALEVALA-AIHEISTA MUSIIKKIA". Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Leevi Madetoja". Archived from the original on 31 December 2005. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Uuno Klami". Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Tauno Marttinen - stanford.edu". Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "The Kalevala in modern art". Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Veljo Tormis data bank". Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ "Metal Invader – Amorphis interview". Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Amorphis official site". Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Ensiferum – News". Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Ensiferum – History". Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Turisas official site – The Varangian Way". Retrieved 22 August 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Amberian Dawn interview – powerofmetal.dk". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Värttinä – Members". Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Vantaa Chamber Choir – Marian virsi". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Taiteilijoiden Kalevala". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ BWW News Desk. "Maija Anttila With Soulgaze Films Presents KALEVALA The Musical in Concert". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "IMDB page for "The day the earth froze"". IMDb. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "RAUTA-AIKA Neljä vuotta, neljä osaa". Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "IMDB page for "Rauta-Aika"". Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "IMDB page for "Jadesoturi"". IMDb. Archived from the original on 8 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Jari Halosen Kalevala floppasi". Yle (in Finnish). 27 November 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ Britt, Ryan (1 March 2023). "Mandalorian Season 3's Biggest Twist Has Sidelined Its Greatest Character". Inverse. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ a b Scott, Ryan (1 March 2023). "The Mandalorian Season 3 Premiere Brings A Star Wars Planet You've Heard About Into Live-Action". Slash Film. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ Viholainen, Aila (2009). "Vellamon kanssa ongelle – eli kuinka merenneitoa kansalliseksi kuvitellaan". Elore. 16 (2). Suomen Kansantietouden Tutkijain Seura ry. doi:10.30666/elore.78806.

- ^ Juha Pentikäinen, Ritva Poom, Kalevala mythology, 1888.

- ^ Aikio, Ante (2012). "An Essay on Saami Ethnolinguistic Prehistory". Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. 266: 63–117. ISBN 978-952-5667-42-4. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Emil Nestor Setälä". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 24 December 2014.

- ^ Eemil Nestor Setälä. "Sammon arvoitus: Isien runous ja usko: 1. "Suomen suku" laitoksen julkaisuja. 1." Helsinki: Otava, 1932..

- ^ Hastings, James (1 January 2003). The Finnish Virgin Mary myth. Kessinger. ISBN 9780766136908. Retrieved 17 August 2010.[permanent dead link]

Further reading[edit]

Translations[edit]

- Crawford, John Martin, ed. (1888), The Kalevala: The Epic Poem of Finland, ISBN 978-0-7661-8938-6. Text at Project Gutenberg: Volume 1, Volume 2, and Complete work.

- Friberg, Eino; Landström, Björn; Schoolfield, George C., eds. (1988), The Kalevala: Epic of the Finnish People, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 978-951-1-10137-6

- Kirby, William Forsell, ed. (1907), The Kalevala: Or the Land of Heroes, Society of Metaphysicians Limited, ISBN 978-1-85810-198-9. Text at Project Gutenberg: Volume 1 and Volume 2.

- Lönnrot, Elias (1989). The Kalevala. Translated by Bosley, Keith. Oxford / New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953886-7.

- Magoun, Francis Peabody, ed. (1963), The Kalevala: Or Poems of the Kaleva District, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-50010-5

- Magoun, Francis Peabody, ed. (1969), The Old Kalevala and Certain Antecedents, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-63235-6 , translation of the 1835 Old Kalevala

- קאַלעװאַלאַ: פֿאָלקס עפּאָס פֿון די פֿינען. Translated by Rosenfeld, Hersh. New York: Marstin Press. 1954.

Retellings[edit]

- Cavazzano, Giorgio; Korhonen, Kari (2022), The Harp Under the Hammer, a sequel for Don Rosa's The Quest for Kalevala featuring Scrooge McDuck and some characters from the Kalevala

- Eivind, R. (1893), Finnish Legends for English Children, near complete prose translation based on Crawford

- Fillmore, Parker Hoysted (1923), The Wizard of the North: A Tale From the Land of Heroes

- Huitula, Kristian (2005), Friberg, Eino (ed.), The Kalevala Graphic Novel, Fantacore, ISBN 978-952-99022-1-7

- Kolehmainen, John Ilmari (1973), Epic of the North

- McNeil, M.E.A (1994), The Magic Storysinger: A Tale from the Finnish Epic Kalevala, Stemmer House, ISBN 978-0-88045-128-4 , a retelling in a style friendly to children

- Rosa, Don (1999), "The Quest for Kalevala", Uncle Scrooge, no. 334, ISBN 978-0-911903-55-3 , a story in tribute to the Kalevala featuring Scrooge McDuck and some characters from the Kalevala

- Steffa, Tim; Kunnas, Mauri, eds. (1997), The Canine Kalevala, Otava, ISBN 978-951-1-12442-9

Analysis[edit]

- Alho, Olli, ed. (1997), Finland: a cultural encyclopedia, Finnish Literature Society, ISBN 978-951-717-885-3

- Branch, Michael; Hawkesworth, Celia, eds. (1994), The Uses of Tradition: a Comparative Enquiry into the Nature, Uses and Functions of Oral Poetry in the Balkans, the Baltic and Africa, ISBN 978-0-903425-38-4

- Ellison, Cori (7 January 2005), "An Epic Gave Finns A Lot to Sing About", The New York Times, retrieved 16 November 2022

- Ervast, Pekka; Jenkins, John Major; Tapio, Joensuu (1916), The Key to The Kalevala, Blue Dolphin Pub., ISBN 978-1-57733-021-9

- Haavio, Martti Henrikki (1952), Väinämöinen, Eternal Sage

- Hämäläinen, Niina (December 2013), ""Do Not, Folk of the Future, Bring up a Child Crookedly!": Moral Intervention and Other Textual Practices by Elias Lönnrot", RMN Newsletter, 7: 43–56

- Honko, Lauri, ed. (1990), Religion, Myth, and Folklore in the World's Epics, Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-0-89925-625-2

- Honko, Lauri, ed. (2002), The Kalevala and the World's Traditional Epics, Finnish Literature Society, ISBN 978-951-746-422-2

- Kallio, Veikko (1994), Finland: A Cultural Outline, Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö, ISBN 978-951-0-19421-8

- Kaukonen, Väinö (1978), Lönnrot ja Kalevala [Lönnrot and The Kalevala]

- Kuusi, Matti, ed. (1977), Finnish Folk Poetry, Finnish literature society, ISBN 978-951-717-087-1

- Oinas, Felix J. (1985), Studies in Finnish Folklore, Finnish Anthropological Society, ISBN 978-951-717-315-5

- Pentikäinen, Juha Y. (1999), Kalevala Mythology, Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-33661-3

- Schoolfield, George C., ed. (1998), A History of Finland's Literature, U of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-4189-3

- Setälä, E.N. (1932), Sammon Arvoitus [The Riddle of the Sampo]

- Siikala, Anna-Leena. "The Kalevalaic Tradition as Finnish Mythology". In: Ethnographica et Folkloristica Carpathica, 12–13 (2002). Megjelent: Mental Spaces and Ritual Traditions pp. 107–122

- Tolley, Clive. "The Kalevala as a Model for our Understanding of the Composition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda." The Retrospective Methods Network (2014).

- Wilson, William A. (1976), Folklore and Nationalism in Modern Finland, Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-32327-9

Encyclopedia[edit]

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). p. 640.

- Wiener, Leo (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

External links[edit]

The full text of Kalevala at Wikisource (in English)

The full text of Kalevala at Wikisource (in English)- Kalevala at Standard Ebooks

- Kalevala: the Epic Poem of Finland at Project Gutenberg

Kalevala public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Kalevala public domain audiobook at LibriVox

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch