Marfa, Texas

Marfa, Texas | |

|---|---|

Downtown Marfa | |

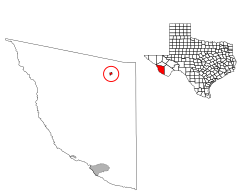

Location of Marfa in Presidio County | |

| Coordinates: 30°18′29″N 104°01′09″W / 30.30806°N 104.01917°W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Presidio |

| Named for | Marfa Strogoff, a character in the novel Michael Strogoff |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Manuel V. Baeza[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.63 sq mi (4.22 km2) |

| • Land | 1.63 sq mi (4.22 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 4,685 ft (1,428 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 1,788 |

| • Density | 998/sq mi (385/km2) |

| Demonym | Marfan |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 79843 |

| Area code | 432 |

| FIPS code | 48-46620[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1340942[1] |

| Website | cityofmarfa |

Marfa is a city in the high desert of the Trans-Pecos in far West Texas, United States, between the Davis Mountains and Big Bend National Park, at an elevation of 4685 feet. It is the county seat of Presidio County, and its population as of the 2020 United States Census was 1,788. The city was founded in the early 1880s as a water stop; the population peaked in the 1930s and has continued to decline each decade since. However, today Marfa is a tourist destination and a major center for minimalist art. Attractions include Building 98, the Chinati Foundation, artisan shops, historical architecture, a classic Texas town square, modern art installments, art galleries, and the Marfa lights.

History[edit]

Marfa was founded in the early 1880s as a railroad water stop. The town was named "Marfa" (Russian for "Martha") at the suggestion of the wife of a railroad executive. Although some historians have hypothesized that the name came from a character in Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov,[5] Marfa was actually named after Marfa Strogoff, a character in Jules Verne's novel Michael Strogoff.[6][7] According to Sterry Butcher of the Texas Monthly, a writer researched the Karamazov story and deemed it false, but did not receive any letters to the editor after he submitted the story to the newspaper, and therefore "No one cared. The story we had suited Marfa just fine."[8]

The town grew quickly during the 1920s.[9]

The Marfa Army Air Field served as a training facility for several thousand pilots during World War II, including the American actor Robert Sterling, before closing in 1945. The base was also used as the training ground for many of the United States Army's chemical mortar battalions.

Marfa experienced economic issues after the war ended and after a drought impaired agricultural output. Artist Donald Judd arrived in 1973 and began buying properties to renovate, which resulted in bohemian interest in the community.[10] In 2012 Vanity Fair described it as a "playground" for "art-world pioneers and pilgrims".[11] Marfa is about 60 miles from the Mexico-U.S. border.

Geography[edit]

Marfa is in northeastern Presidio County within the Chihuahuan Desert. The town is approximately 20 miles south of Fort Davis on Texas Route 17 and about 18 miles west of Alpine on US Route 67.[12] According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1.6 sq mi (4.1 km2), all land.

Climate[edit]

Marfa experiences a semi-arid climate (BSk) with hot summers and cool winters. Due to its elevation and aridity, the diurnal temperature variation is substantial.

| Climate data for Marfa #2, Texas. (Elevation 4,790ft) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) | 86 (30) | 90 (32) | 96 (36) | 102 (39) | 106 (41) | 103 (39) | 104 (40) | 100 (38) | 95 (35) | 86 (30) | 79 (26) | 106 (41) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 60.2 (15.7) | 63.9 (17.7) | 71.2 (21.8) | 78.8 (26.0) | 85.8 (29.9) | 91.2 (32.9) | 89.6 (32.0) | 87.5 (30.8) | 83.6 (28.7) | 77.3 (25.2) | 67.6 (19.8) | 60.8 (16.0) | 76.5 (24.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 42.9 (6.1) | 46.0 (7.8) | 52.3 (11.3) | 60.1 (15.6) | 67.9 (19.9) | 74.4 (23.6) | 74.9 (23.8) | 73.3 (22.9) | 68.7 (20.4) | 60.7 (15.9) | 50.5 (10.3) | 43.7 (6.5) | 59.6 (15.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 25.7 (−3.5) | 28.1 (−2.2) | 33.5 (0.8) | 41.4 (5.2) | 50.1 (10.1) | 57.6 (14.2) | 60.2 (15.7) | 59.1 (15.1) | 54.0 (12.2) | 44.1 (6.7) | 33.4 (0.8) | 26.6 (−3.0) | 42.8 (6.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) | 0 (−18) | 6 (−14) | 17 (−8) | 27 (−3) | 39 (4) | 53 (12) | 50 (10) | 36 (2) | 16 (−9) | −1 (−18) | 2 (−17) | −2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.42 (11) | 0.47 (12) | 0.31 (7.9) | 0.59 (15) | 1.17 (30) | 1.78 (45) | 2.73 (69) | 2.89 (73) | 2.57 (65) | 1.39 (35) | 0.58 (15) | 0.50 (13) | 15.41 (391) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.7 (1.8) | 0.6 (1.5) | 0.1 (0.25) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.4 (1.0) | 2.2 (5.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 59 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute[13] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 3,553 | — | |

| 1930 | 3,909 | 10.0% | |

| 1940 | 3,805 | −2.7% | |

| 1950 | 3,603 | −5.3% | |

| 1960 | 2,799 | −22.3% | |

| 1970 | 2,647 | −5.4% | |

| 1980 | 2,466 | −6.8% | |

| 1990 | 2,424 | −1.7% | |

| 2000 | 2,121 | −12.5% | |

| 2010 | 1,981 | −6.6% | |

| 2020 | 1,788 | −9.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

2020 census[edit]

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 678 | 37.92% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 13 | 0.73% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 4 | 0.22% |

| Asian (NH) | 12 | 0.67% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 2 | 0.11% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 24 | 1.34% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,055 | 59.0% |

| Total | 1,788 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 1,788 people, 802 households, and 300 families residing in the city.

2010 census[edit]

As of the 2010 United States Census, 1,981 people, 864 households, and 555 families resided in the city.[4] The population density was 1,354 inhabitants per square mile (523/km2). The 1,126 housing units averaged 719.1 per square mile (276.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 30% White, 0.4% African American, 0.2% Native American, 0.05% Asian, 7.50% from other races, and 0.75% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 68.7% of the population. Of 863 households, 29.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.4% were married couples living together, 13.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.6% were not families. About 31.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 2.99. The age distribution of the population shows 24.9% under the age of 18, 7.9% from 18 to 24, 24.2% from 25 to 44, 24.5% from 45 to 64, and 18.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.9 males. The median income for a household in the city was $24,712, and for a family was $32,328. Males had a median income of $25,804 versus $18,382 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,636. About 15.7% of families and 20.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.6% of those under age 18 and 26.9% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture[edit]

The area around Marfa is known as a cultural center for contemporary artists and artisans. In 1971, Minimalist artist Donald Judd moved to Marfa from New York. After renting summer houses for a few years, he bought two large hangars and some smaller buildings and began to install his art permanently. This had started with his building in New York but the buildings in Marfa allowed him to install his works on a larger scale. In 1976, he bought the first of two ranches that became his primary places of residence, continuing a long love affair with the desert landscape surrounding Marfa. Later, with assistance from the Dia Art Foundation in New York, Judd acquired decommissioned Fort D.A. Russell, and in 1979 began transforming the fort's buildings into art spaces. Judd's vision was to house large collections of individual artists' work on permanent display, as a sort of antimuseum. Judd believed the prevailing model of many museums, where various art exhibits are shown for limited times, does not allow the viewer an understanding of the artist or their work as they had intended.

Following Judd's death in 1994, two foundations have worked to maintain his legacy: the Chinati Foundation and Judd Foundation. Since its inauguration in 1986, Chinati has held an open-house event that attracts visitors from around the world to visit Marfa's art.[18] Between 1997 and 2008, both foundations cosponsored this event. The Chinati Foundation now occupies more than 30 buildings in Marfa and has permanently displayed work by 13 artists.[19]

In recent years, a new wave of artists has moved to Marfa to live and work. As a result, new gallery spaces have opened in the downtown area. The Crowley Theater and its annex host public events with seating for over 175 as a public service to nonprofit foundations. Furthermore, The Lannan Foundation has established a writers-in-residency program, a Marfa theater group has formed, and a multifunctional art space called Ballroom Marfa has begun to show art films, host musical performances, and exhibit other art installations. The city is also 37 miles (60 km) from Prada Marfa, a pop art exhibit, and is home to Cobra Rock Boot Company and The Wrong Store.

Marfa Myths, an annual music festival and multidisciplinary cultural program, was founded in 2014 by the nonprofit contemporary arts foundation Ballroom Marfa and Brooklyn-based music label Mexican Summer. The festival brings together a diversity of emerging and established artists and musicians to work creatively and collaboratively across music, film, and visual arts contexts. The festival is inherently embedded in the landscape of Far West Texas and deeply engaged with Marfa's cultural history and present-day community.

Building 98, also located in Marfa, is a project of the International Woman's Foundation, which has operated an artist-in-residency program since 2002. The International Woman's Foundation was responsible for placing Fort D.A. Russell on the National Register of Historic Places as an effort to preserve the historic importance of the site.[20] The facility's studio galleries host artists who desire to exhibit work in the region at a premier venue. In late September 2012 through early April 2013, the foundation held a major retrospective of the works of Wilhelmina Weber Furlong at Building 98 featuring over 75 unseen works of the early American woman modernist. Building 98 is located at historic Fort D. A. Russell; it is the home of Marfa's German POW murals.[21][22] The facility also features the George Sugarman sculpture courtyard.[20]

Marfa lights[edit]

Apart from Donald Judd and modern art, Marfa may be most famous for the Marfa lights, visible on clear nights between Marfa and the Paisano Pass when one is facing southwest (toward the Chinati Mountains). According to the Handbook of Texas Online, "at times they appear colored as they twinkle in the distance. They move about, split apart, melt together, disappear, and reappear. Presidio County residents have watched the lights for over a hundred years." The first historical record of them dates to 1883.[23] Presidio County has built a viewing station 9 miles east of town on US 67 near the site of the old air base. Each year, enthusiasts gather for the annual Marfa Lights Festival. The lights have been featured and mentioned in various media, including the television show Unsolved Mysteries and an episode of King of the Hill ("Of Mice and Little Green Men") and in an episode of the Disney Channel Original Series So Weird. A book by David Morrell, 2009's The Shimmer, was inspired by the lights. The Rolling Stones mention the "lights of Marfa" in the song "No Spare Parts" from the 2011 re-release of their 1978 album Some Girls.

In popular culture[edit]

Various movie productions have filmed in and around parts of Marfa. The 1950 film High Lonesome and the 1956 Warner Bros. film Giant were filmed in Marfa.[citation needed]

In August 2006, two films were partially shot in Marfa: There Will Be Blood and No Country for Old Men.[24][25]

Larry Clark's 2012 film Marfa Girl was filmed exclusively in Marfa.[26] Also, Far Marfa, written and directed by Cory Van Dyke, made its debut in 2012.[27]

Morley Safer presented a 60 Minutes segment in on August 4, 2013, titled "Marfa, Texas, the Capital of Quirkiness."[28]

In 2017, Marfa was featured as the setting of the Amazon series I Love Dick, an adaptation of Chris Kraus's 1997 novel, which was set in Pasadena, California.[29][30][31]

Marfa is featured in the 2019 Simpsons episode "Mad About the Toy."[32]

"Marfa" is the eighth track on Texas symphonic rock band Mother Falcon's second studio album, You Knew.[33] It is also the name of songs by Wildcat! Wildcat!, S. Carey, and Paul Cauthen ("Marfa Lights").[34][35][36]

Marfa is featured in Ben Lerner's 2014 novel 10:04.[37]

Media[edit]

Marfa is home to National Public Radio-affiliated station KRTS.

Marfa houses the offices of the Big Bend Sentinel, serving Marfa, and International/Internacional, serving Presidio, in one building.[38] The former is a weekly newspaper covering the areas of Marfa, Fort Davis, Presidio, and far West Texas. Marfa Magazine is a yearly publication distributed from Marfa, founded and operated by Johnny Calderon Jr. It focuses on issues and general information about Marfa, Alpine, and Fort Davis.[citation needed]

Infrastructure[edit]

On October 1, 2009, the city council voted to no longer have a local police department. At the time, the Presidio County Sheriff's Department and Texas Highway Patrol provided law enforcement for the city, as well as the county as a whole. As of 2019, however, the Marfa Police Department has been re-established, and five officers, including a chief and lieutenant, oversee law enforcement within the city limits.

Education[edit]

Marfa is served by the Marfa Independent School District. Within it, Marfa Elementary School and Marfa Junior/Senior High School serve the city.

Hispanic students attended the segregated Blackwell School from 1909 to 1965. The school was authorized to be a National Historic Site in 2022.[39]

Marfa International School,[40] a private school, opened in 2012,[citation needed] serving students in grades 1–8, with scholarships available based on need.[citation needed] However, it closed in 2016.[41]

Presidio County is within the Odessa College District for community college.[42]

Public library[edit]

Marfa and the surrounding area are served by the Marfa Public Library, which houses a diverse collection in a variety of formats. The library began in 1947 when the Marfa Lions Club and the Marfa Study Club agreed to establish a library for the citizens of the area.[43] The library was originally housed in the historic U.S.O. building, but was moved to a city-owned building after the city took over the project. After meeting the requirements of the Texas State Library, it became a member of the Texas Trans-Pecos Library System.[43] The present library building was donated to the City of Marfa in 1973 by the first chairperson, Laura Bailey, and her husband Bishop.[43] Future expansions and renovations to the current building are also planned.

Transportation[edit]

Presidio County operates the Marfa Municipal Airport, located north of the city in unincorporated Presidio County.

Commercial air service is available at either Midland International Airport or El Paso International Airport.[44] The airports are, respectively, 180 mi (290 km) northeast, and 190 mi (310 km) northwest.[citation needed]

Greyhound Lines operates an intercity bus service from the Western Union office.[45] Amtrak's Sunset Limited, which operates between New Orleans and Los Angeles three days a week, passes through the city, but does not stop; the nearest station is located in Alpine, 26 mi (42 km) northeast.

Highways[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Marfa". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Cities: Marfa - Texas State Directory Online". www.txdirectory.com.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Wilson, Thomas (2001). "How Marfa, Texas Got Its Name". Journal of Big Bend Studies. Sul Ross State University. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ Popik, Barry (October 3, 2008). "Marfa (summary)". Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Marfa". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 48: 295. 1944. ISSN 0038-478X. LCCN 12-20299. OCLC 1766223. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Butcher, Sterry (December 2017). "The Marfa Mystique". Texas Monthly. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "Presidio County, Texas Genealogy". FamilySearch. September 16, 2022.

- ^ Swartz, Mimi (January 22, 2020). "A Battle for the Soul of Marfa". Texas Monthly. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Wilsey, Sean; Beal, Daphne (July 2012). "Lone Star Bohemia". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Texas Atlas & Gazeteer, DeLorme, 4th edition, 2001, p. 63 ISBN 0-89933-320-6

- ^ "MARFA 2, TEXAS (415596), Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ https://www.census.gov/ [not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "Open House 1995 and 1996" (PDF). The Chinati Foundation Newsletter (in English and Spanish). Vol. 2. Marfa, TX: The Chinati Foundation. 1996. p. 23. ISSN 1083-5555.

- ^ "The Chinati Foundation Collection". The Chinati Foundation. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "Fort D. A. Russell". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- ^ "Marfa Public Radio". Talk at 10 interview. Kay Burnet Studios. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ^ The Biography of Wilhelmina Weber Furlong: The Treasured Collection of Golden Heart Farm by Clint B. Weber, ISBN 978-0-9851601-0-4

- ^ "Marfa lights." Handbook of Texas.

- ^ Whitney Joiner, "Postcard: Marfa. A far-flung Texas town stars in two of this year's Oscar-nominated films. Yet a proposed truck route could end its precious seclusion. The battle to stay off the beaten path", TIME 171.8 (February 25, 2008): 6. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,1713476,00.html

- ^ Marfa (pop 2,400), the desert town that will be the star of the Oscars Daily Telegraph article by Catherine Elsworth in Issue 47,499 dated 21 February 2008

- ^ "Five Questions with Marfa Girl Director Larry Clark". Filmmaker Magazine. November 14, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ^ "'Far Marfa' Captures the Romance of West Texas Outpost".

- ^ "Marfa, Texas: The capital of quirkiness". CBS News.

- ^ "What Does the New Show I Love Dick Say About Marfa?". Texas Monthly. August 26, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Ro, Lauren (May 15, 2017). "'I Love Dick' TV adaptation takes the action to Marfa". Curbed. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (February 18, 2016). "Amazon Orders 'I Love Dick' Comedy Pilot From Jill Soloway". Deadline. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Dan Solomon (January 8, 2019). "Marfa Is Now Such a Stereotype They Can Mock It on 'The Simpsons'". Texas Monthly.

- ^ "An Interview With Chamber Rockers Mother Falcon". KRTS 93.5 FM Marfa Public Radio. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Carroll, Jim. "Wildcat! Wildcat!: No Moon at All". The Irish Times. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ "S. Carey: Hoyas EP". Pitchfork. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ "VICE - The Gospel According to Paul Cauthen". www.vice.com. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Witt, Emily (January 3, 2015). "Ben Lerner: 'People say, "Oh, here's another Brooklyn novel by a guy with glasses"'". the Guardian. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ Butcher, Sterry (October 2019). "Long Live the 'Big Bend Sentinel.' Viva 'El Internacional.'". Texas Monthly. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "President Biden Designates Blackwell School National Historic Site as America's Newest National Park". US Department of the Interior. October 18, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "Marfa International School - Marfa, Texas". www.marfais.org. Archived from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ "Marfa International School :: Dixon Water Foundation".

- ^ "Texas Education Code Sec. 130.193. ODESSA COLLEGE DISTRICT SERVICE AREA".

- ^ a b c "Who We Are". Marfa Public Library. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ Lawlor, Julia (April 29, 2005). "The Great Marfa ... Land Boom". The New York Times. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "Marfa, Texas[permanent dead link]." Greyhound Lines.

External links[edit]

- Marfa Chamber of Commerce

- The Big Bend Sentinel – local newspaper

- View Historic Photos of Marfa from the Marfa Public Library, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Marfa! Marfa! Marfa! – 1998 article by Magdalin Leonardo

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch