Marshall House (Alexandria, Virginia)

| Marshall House | |

|---|---|

The Marshall House Inn (photo 1861) | |

| General information | |

| Type | Hotel |

| Address | 480 King Street |

| Town or city | Alexandria, Virginia |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 38°48′16.90″N 77°2′40.45″W / 38.8046944°N 77.0445694°W |

| Demolished | 1950s |

The Marshall House was an inn that stood at 480 King Street (near the southeast corner of King Street and South Pitt Street) in Alexandria, Virginia. At the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861, the house was the site of the killing of Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth during the Union Army's takeover of Alexandria. Ellsworth was a popular and highly prominent officer and a close friend of President Abraham Lincoln.

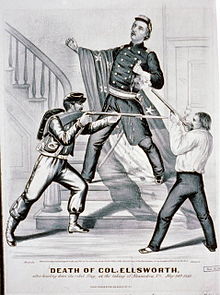

Ellsworth was the first conspicuous Union Army casualty and the first officer killed in battle during the war. He was shot by the inn's proprietor James W. Jackson after removing a Confederate flag from the roof of the inn. Jackson was immediately killed after he killed Ellsworth. Ellsworth's death became a cause célèbre for the Union, while Jackson's death became the same for the Confederacy.

History[edit]

Ellsworth, a young Illinois lawyer who was a friend of the Lincoln's and founder of the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment known as the "Fire Zouaves", was killed at the Marshall House on May 24, 1861 (the day after Virginia's secession was ratified by referendum) during the Union Army's take-over of Alexandria.[1][2][3] During the month before the event, the inn's proprietor, James W. Jackson, had raised from the inn's roof a large Confederate flag that President Lincoln and his Cabinet had reportedly observed through field glasses from an elevated spot in Washington.[3] Jackson had reportedly stated that the flag would only be taken down "over his dead body".[3][4][5]

Before crossing the Potomac River to take Alexandria, soldiers serving under Ellsworth's command observed the flag from their camp through field glasses and volunteered to remove it.[6] Having seen the flag after landing in Alexandria, Ellsworth and seven other soldiers entered the inn through an open door. Once inside, they encountered a man dressed in a shirt and trousers, of whom Ellsworth demanded what sort of a flag it was that hung upon the roof.[1][6]

The man, who seemed greatly alarmed, declared he knew nothing of it, and that he was only a boarder there. Without questioning him further, Ellsworth sprang up the stairs followed by his soldiers, climbed to the roof on a ladder and cut down the flag with a soldier's knife. The soldiers turned to descend, with Private Francis E. Brownell leading the way and Ellsworth following with the flag.[1][3][6]

As Brownell reached the first landing place, Jackson jumped from a dark passage, leveled a double-barreled gun at Ellsworth's chest and discharged one barrel directly into Ellsworth's chest, killing him instantly. Jackson then discharged the other barrel at Brownell, but missed his target. Brownell's gun simultaneously shot, hitting Jackson in the middle of his face. Before Jackson dropped, Brownell repeatedly thrust his bayonet through Jackson's body, sending Jackson's corpse down the stairs.[1][3][6]

Ellsworth became the first Union officer to die while on duty in the Civil War.[2] Brownell, who retained a piece of the flag, was later awarded a Medal of Honor for his actions.[7][8][9]

Ellsworth's body was taken back across the Potomac to Washington, D.C. and was laid in state in the East Room at the White House.[10] Immediately after the incident, thousands of Union supporters rallied around Ellsworth's cause and enlisted, and "Remember Ellsworth" became a patriotic slogan.[7] The 44th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment called itself the "Ellsworth Avengers" as well as "The People's Ellsworth Regiment".[11][12] Confederates meanwhile hailed Jackson as a martyr to their cause.[3][13]

Soldiers and souvenir hunters carried away pieces of the flag and inn as mementos, especially portions of the inn's stairway, balustrades and oilcloth floor covering.[3][11][14] After the war ended, the Marshall House served as a location for a series of small businesses, but still attracted tourists from both the North and the South.[3] Largely reconstructed after an 1873 fire that an arsonist caused, the building was torn down around 1950.[3][15]

The City of Alexandria has erected a wayfinding sign near the southeast corner of King Street and South Pitt Street. The sign relates the history and significance of the Marshall House, together with historical photographs and other information.[13]

Historical marker[edit]

In 1999, sociologist and historian James W. Loewen noted in his book Lies Across America that the Sons of Confederate Veterans had placed a bronze plaque on the side of a Holiday Inn that had been constructed on the former site of the Marshall House. Loewen reported that the plaque described Jackson's death but omitted any mention of Ellsworth.[16] Adam Goodheart further discussed the incident and the plaque (which was then within a blind arch near a corner of a Hotel Monaco) in his 2011 book 1861: The Civil War Awakening.[17]

The plaque called Jackson the "first martyr to the cause of Southern Independence" and said he "was killed by federal soldiers while defending his property and personal rights ... in defence of his home and the sacred soil of his native state".[18] In full, it read:

THE MARSHALL HOUSE

stood upon this site, and within the building

on the early morning of May 24,

JAMES W. JACKSON

was killed by federal soldiers while defending his property and

personal rights as stated in the verdict of the coroners jury.

He was

the first martyr to the cause of Southern Independence.

The justice of history does not permit his name to be forgotten.

–––––––––––––––– O –––––––––––––––

Not in the excitement of battle, but coolly and for a great principle,

he laid down his life, an example to all, in defence of his home and

the sacred soil of his native state.

VIRGINIA

In 2013, WTOP reported that some Alexandria residents were advocating the removal of the plaque, but that city officials had no control over the matter as the plaque was on private property.[19] However, in December 2016, Marriott International purchased The Monaco, added it to its boutique Autograph Collection and renamed it as "The Alexandrian".[20] By October 2017, the plaque was removed from The Alexandrian and had given it to the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.[21]

Artifacts[edit]

During and after the Marshall House incident, relics associated with Ellsworth's death became prized souvenirs. President Lincoln kept the captured Marshall House flag, with which his son Tad often played and waved.[4] The New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center in Saratoga Springs now holds in its collections most of the flag, as well as Ellsworth's uniform. The uniform contains a hole through which a slug apparently entered.[22]

The Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. holds in its collections a fragment of the flag, a blood-stained piece of oilcloth and a scrap of red bunting that remain from the encounter at the Marshall House.[23] Bates College's Special Collections Library in Lewiston, Maine holds another fragment of the flag.[24]

In 1894, Brownell's widow was offering to sell small pieces of the flag for $10 and $15 each. A fragment of the flag that Brownell had given to an early mentor at the time of Ellsworth's funeral was sold during the 21st century after being retained by the mentor's family for many years.[9]

The Fort Ward Museum and Historic site in Alexandria displays the kepi that Ellsworth wore when he was killed, patriotic envelopes bearing his image, most of a star from the flag that is still stained with Ellsworth's blood, and the "O" from the Marshall House sign that a soldier took as a souvenir.[13][25]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d (1) "The Murder of Colonel Ellsworth". Harper's Weekly. 5 (232): 357–358. 1861-06-08. Retrieved 2019-01-28 – via Internet Archive.

(2) "The Murder of Ellsworth". Harper's Weekly. 5 (233): 369. 1861-06-15. Retrieved 2019-01-28 – via Internet Archive. - ^ a b "Encounter at the Marshall House". Georgia's Blue and Gray Trail Presents America's Civil War. Georgia's Historic High Country Travel Association, the State of Georgia and Golden Ink. Archived from the original on 2018-01-01. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Snowden, W.H. (1894). Alexandria, Virginia. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company. pp. 5–9. LCCN rc01002851. OCLC 681385571. Retrieved 2019-01-29 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Leepson, Marc (Fall 2011). Greenberg, Linda (ed.). "The First Union Civil War Martyr: Elmer Ellsworth, Alexandria, and the American Flag" (PDF). The Alexandria Chronicle. Alexandria, Virginia: Alexandria Historical Society, Inc.

- ^ Hawthorne, Frederick W. "Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments", The Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides, Hanover PA 1988 p. 54 & 55

- ^ a b c d "Letter by Lorrequer, 1861-05-29, and statement of Brownell, Mr. F. A." 11th Infantry Regiment: New York: Civil War Newspaper Clippings: Unit History Project: New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. 2006-03-19. Archived from the original on 2019-02-02. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- ^ a b Edwards, Owen (April 2011). "The Death of Colonel Ellsworth". Smithsonian Magazine. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ (1) "Elmer Ellsworth". U.S. National Park Service. 2015-06-17. Archived from the original on 2019-01-29. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

(2) "Brownell's Medal of Honor". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2002-10-16. Retrieved 2008-02-05. - ^ a b "A Fragment of the Original Confederate Flag Cut Down by Col. Elmer Ellsworth at the Marshall House, and For Which He Lost His Life: Along with a note and presentation envelope for the fragment from "Ellsworth's Avenger", Frank E. Brownell, which he gave to his mentor on the way to Ellsworth's funeral". Ardmore, Pennsylvania: The Raab Collection. Archived from the original on 2019-01-28. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ^ Goodheart, p. 288.

- ^ a b Goodheart, p. 289.

- ^ "44th Infantry Regiment: Civil War: Ellsworth Avengers; People's Ellsworth Regiment". New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. 2018-01-25. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ a b c "Wayfinding: Marshall House". City of Alexandria, Virginia. 2018-03-28. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ (1) "Plate 1. Marshal House, Alexandria". Collections. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution: National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

Relic hunters soon carried away from the hotel everything movable, including the carpets, furniture, and window shutters, and cut away the whole of the staircase and door where Ellsworth was shot.

(2) Boltz, Martha M. (2011-05-18). "Jackson and Ellsworth: Death on both sides of the Civil War". The Washington Times. - ^ Bertsch, Amy (2016-09-29). "A Civil War landmark destroyed by fire" (PDF). Alexandria Times: Out of the Attic. Office of Historic Alexandria: City of Alexandria, Virginia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ Loewen, James W. (2000). The Clash of the Martyrs: Virginia: Alexandria. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 294–295. ISBN 9781595586766. LCCN 99014212. OCLC 892054466. Retrieved 2019-01-26 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Goodheart

- ^ (1) Goodheart, p. 292.

(2) Pfingsten, Bill (ed.). ""The Marshall House" marker". HMdb: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

(3) Groeling, Meg (2017-10-23). "Colonel Elmer Ellsworth and the Marshall House Hotel Plaque". Emerging Civil War: Battlefield Markers & Monuments. Archived from the original (blog) on 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-01-25 – via WordPress. - ^ wtopstaff (2013-02-02). "Curious plaque tells forgotten story". WTOP. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ Barton, Mary Ann (2016-12-14). "Hotel Monaco Sold, to Become The Alexandrian". Patch: Old Town Alexandria. Patch Media. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

As of Dec. 20, Sage Hospitality began managing the hotel while also becoming a franchised member of Marriott's Autograph Collection along with the Morrison House in Alexandria, after sale of properties.

- ^ (1) Groeling, Meg. "Colonel Elmer Ellsworth and the Marshall House Hotel Plaque". Emerging Civil War: Battlefield Markers & Monuments. Archived from the original (blog) on 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-01-25 – via WordPress.

(2) Pfingsten, Bill (ed.). ""The Marshall House" marker". HMdb: The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2019-01-26. - ^ (1) Carola, Chris (Associated Press) (2011-06-01). "Sensational Civil War death explored in 3 places". Destination Travel. NBCNEWS.com. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

NEW YORK STATE MILITARY MUSEUM: .....

The museum's collection includes the uniform coat Ellsworth was wearing when Jackson fired a shotgun into his chest as the 24-year-old officer descended the stairs leading to the Marshall House's roof. The coat, still showing the hole where the slug entered, is on display, along with one of Ellsworth's swords and a Zouave drill manual.

Jackson's flag — originally 14 feet by 24 feet — is among the museum's collection of more than 800 Civil War battle flags, the largest state collection in the nation. Large swaths of the banner were cut up for souvenirs after Ellsworth's death; about 55 percent of the original flag survives. One of several large stars on Jackson's flag was removed and saved by Ellsworth's uncle, who later donated the item to a local Civil War veterans group. The neighboring Town of Saratoga came into possession of the star, which was donated to the museum in August 2006, reuniting it with the flag for the first time in more than 140 years.

(2) "About the Museum". New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. 2016-08-02. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2019-01-30.The artifacts include uniforms, weapons, artillery pieces, and art. A significant portion of the museum's collection is from the Civil War. Notable artifacts from this conflict include Colonel Elmer Ellsworth's (the Union's first martyr) uniform, ... .

(3) "Marshall House Flag Confederate National Flag, First National Pattern, 1861". New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. 2016-09-08. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

(4) "Press Release: Star Reunited After 140 Years wth Historic Elmer Ellsworth Flag". New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. 2006-08-04. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2019-01-30. - ^ (1) "Fragment of Confederate flag cut down by Colonel Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, 1861". Smithsonian Institution Press. 2001. Archived from the original on 2002-04-23.

(2) Goodheart, p. 292. - ^ "Scope and Content Note". Guide to the Benjamin F. Hayes papers, 1854, n.d.: MC096. Lewiston, Maine: Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library, Bates College. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

The journal also includes several loose pieces of paper including one paper with a red piece of cloth pinned to it. This paper has a note claiming that "This is a piece of the flag which was raised over the mansion house in Alexandria by Col. E. E. Ellsworth just before his assassination."

- ^ Carola, Chris (Associated Press) (2011-06-01). "Sensational Civil War death explored in 3 places". Destination Travel. NBCNEWS.com. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

FORT WARD MUSEUM AND HISTORIC SITE: .....

In addition to displays on the everyday life of Civil War soldiers, the museum features an exhibit on the "Ellsworth incident."

The exhibit includes a lock of his hair, a red kepi (cap) he wore, photographs of the young officer in uniform and contemporary published accounts of his death at the hands of James Jackson.

Most of a star from Jackson's secessionist flag, still stained with Ellsworth's blood, is on display, along with the "O" from the Marshall House sign, one of the many pieces of the structure torn off the building by souvenir-hunting Union soldiers seeking a memento from the spot where Ellsworth was slain.

References[edit]

Goodheart, Adam (2012). 1861: The Civil War Awakening. New York: Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc. ISBN 9781400032198. LCCN 2010051326. OCLC 973512612. Retrieved 2019-01-25 – via Google Books.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Marshall House, Alexandria Virginia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Marshall House, Alexandria Virginia at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch