Music of Sudan

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Sudan |

|---|

The rich and varied music of Sudan has traditional, rural, northeastern African roots[1] and also shows Arabic, Western or other African influences, especially on the popular urban music from the early 20th century onwards. Since the establishment of big cities like Khartoum as melting pots for people of diverse backgrounds, their cultural heritage and tastes have shaped numerous forms of modern popular music.[2] In the globalized world of today, the creation and consumption of music through satellite TV or on the Internet is a driving force for cultural change in Sudan, popular with local audiences as well as with Sudanese living abroad.

Even after the secession of South Sudan in 2011, the Sudan of today is very diverse, with five hundred plus ethnic groups spread across the territory of what is the third largest country in Africa. The cultures of its ethnic and social groups have been marked by a complex cultural legacy, going back to the spread of Islam, the regional history of the slave trade and by indigenous African cultural heritage. Though some of the ethnic groups still maintain their own African language, most Sudanese today use the distinct Sudanese version of Arabic.

Due to its geographic location in Africa, where African, Arabic, Christian and Islamic cultures have shaped people's identities, and on the southern belt of the Sahel region, Sudan has been a cultural crossroads between North, East and West Africa, as well as the Arabian Peninsula, for hundreds of years. Thus, it has a rich and very diverse musical culture, ranging from traditional folk music to Sudanese popular urban music of the 20th century and up to the internationally influenced African popular music of today.

Despite religious and cultural objections towards music and dance in public life, musical traditions have always enjoyed great popularity with most Sudanese. Apart from singing in Standard Arabic, the majority of Sudanese singers express their lyrics in Sudanese Arabic, thereby touching the feelings of their national audience as well as the growing number of Sudanese living abroad, notably in Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries. Even during times of wide-ranging restrictions of public life imposed by the government, public concerts or the celebration of weddings and other social events with music and dance have always been part of cultural life in Sudan.[3]

Folk music and other traditional musical forms[edit]

Rural traditional music and dance[edit]

As in other African regions, the traditional musical styles of Sudan are ancient,[a] rich and diverse, with different regions and ethnic groups having many distinct musical traditions. Music in Africa has always been very important as an integral part of religious and social life of communities. Performances of songs, dance and instrumental music are used in rituals and social ceremonies like weddings, circumcision rites or to accompany the long camel treks of the Bedouins. In these performances, music always has been a social event, marked by the combination of performers, lyrics, music and the participation of the community, like dancing or other types of sharing a musical event. Traditional music and its performance have been handed down from generation to generation by accomplished musicians to younger generations and was not written down, except in recent times by formally trained musicians or ethnomusicologists.[b][6][7]

In contrast to traditional Arabic music, most Sudanese music styles are pentatonic, and the simultaneous beats of percussion or singing in polyrhythms are further prominent characteristics of Sudanese sub-Saharan music.[8] The music of Sudan also has a strong tradition of lyrical expression that uses oblique metaphors, speaks about love, the history of a tribe or the beauty of the country. In his essay 'Sudanese Singing 1908–1958', author El Sirr A. Gadour translated an example for the lyrics of a love song from the beginning of the 20th century as follows:[9]

O beautiful one, draw near

Reveal your cheek's scarifications

Let my elation be hallucination in love

The sting of a scorpion

Is more bearable than your disdain.

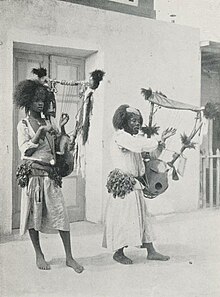

One of the most typical East African instruments, called tanbūra or kissar in Nubian music,[10] was traditionally played by the singers as the usual accompaniment for such songs, but this Sudanese lyre has largely been replaced in the 20th century by the Arabic oud.[c] Drums, hand clapping and dancing are other important elements of traditional musical performances, as well as the use of other African instruments, like traditional xylophones, flutes or trumpets. One example for this are the elaborate wooden gourd trumpets, called al Waza,[12][13] played by the Berta people of the Blue Nile state.

The History of the World in 100 Objects features a large wooden slit drum in the shape of a buffalo from southern Sudan, probably made in the 19th century for traditional performances in larger ensembles or to summon warriors, that is now held in the British Museum in London.[14] A copper kettle drum that was reputedly used by Mahdist forces in the Battle of Omdurman (1898) is in the collection of the National Army Museum in London.[15]

The role of women in traditional music[edit]

In many ethnic groups, distinguished women play an important role in the social celebration of a tribe's virtues and history. In her report about women as singers in Darfur, the ethnomusicologist Roxane Connick Carlisle recounts her fieldwork during the 1960s in three ethnic groups. She describes the common traits of these bards from the Zaghawa ethnic group like this:[16]

"Free vocal rhythm and simple meter throughout, undulating and generally descending solo melodies ranging within an octave, great importance given to meaningful text, a syllabic setting of text to tone level, and a generally relaxed and thoughtful performance of songs – these are the traits present in the repertories of Zaghawi female bards and non-specialist singers. (...) Her personal character must have won the respect of her people, before she can be acceptable functionally as someone with power to move their thoughts and their emotional reactions into the areas she directs. She must be acknowledged as the most clever and witty singer; often she must embody the idea of physical attraction, and particularly she must have the gift of poetry and improvisation, all this encompassed in a person of dignified bearing."

— Roxane Connick Carlisle, Women singers in Darfur, Sudan Republic (1976), p. 266

Another traditional form of women's role in oral poetry are the songs of praise or ridicule of singers in western Sudan, called Hakamat. These are women of high social standing, respected for their eloquence, intuition and decisiveness, who may both incite or vilify the men of their tribe, when engaged in feuds with other tribes. The social impact of these Hakamat can be so strong, that they have been invited by peacebuilding initiatives in Darfur to exert their influence for conflict resolution or contemporary social issues, like environmental protection.[17][18]

Sudanese women are also known both at home and in the wider region for their role as singers and musicians playing the dalooka drum in aghani al-banat (transl.: Girls' songs)[19] as well as for their spiritual musical performances called zār, believed to be able to exorcise evil spirits from possessed individuals.[20][21]

Zikr rituals as religious forms of recitation and performance[edit]

The numerous brotherhoods of Sufi dervishes in Sudan are religious, mystical groups that use prayers, music and ritual dance to achieve an altered state of consciousness in an Islamic tradition called zikr (remembrance). These ritualized zikr ceremonies are, however, not considered by the faithful as musical performances, but as a form of prayer. Each order or lineage within an order has one or more forms for zikr, the liturgy of which may include recitation, instrumental accompaniment by drums, dance, costumes, incense, and is sometimes leading to ecstasy and trance.[22] Zikr rituals are most often celebrated on late Friday afternoons, like the one at the tomb of Sheikh Hamed el-Nil in Omdurman.[23][24]

Brass bands and the origins of modern Sudanese music[edit]

From the early 1920s onwards, radio, records, film and later television have contributed to the development of Sudanese popular music by introducing new instruments and styles. Already during the Turkish-Egyptian rule and later during the Anglo-Egyptian condominium until independence, first Egyptian, and then British military bands left their mark, especially through the musical training of Sudanese soldiers and by introducing Western brass instruments.[25] According to social historian Ahmad Sikainga, "Sudanese members of military bands can be regarded as the first professional musicians, taking the lead in the process of modernization and indigenisation."[26][d] Today still, such marching bands represent a characteristic element in Sudan, playing the National Anthem on Independence Day and other official celebrations.

Development of modern Sudanese music[edit]

The 1920s: hageeba, the origin of modern popular music in Sudan[edit]

The strongest stylistic influence in the development of modern popular Sudanese music has become known as hageeba music (pronounced hagee-ba and meaning "briefcase"). The name hageeba, however, was only applied much later to popular songs from the 1920s, when radio presenter Ahmed Mohamed Saleh talked about old records, collected in his briefcase for his show hageebat al-fann (artistic briefcase), that he presented on Radio Omdurman during the 1940s.[e]

In terms of the history of music of Sudan, the label hageeba applies to an important change in the development of modern music: A new urban style of singing and lyrics was evolving, moving away from tribal folk songs and the melodies of religious, devotional singing. This style was inaugurated by the singer Muhamad Wad El Faki, as well as others like Muhamad Ahmed Sarour, who were later inspired by Wad El Faki.[9] These songs were initially inspired by the vocal tradition of Islamic praise chanting for the prophet Muhammad, known as madeeh.[f] Gradually, melodies known from madeeh were used by singers like Wad El Faki and others to accompany new, non-religious lyrics. During his childhood years at a religious school, called khalwa in Sudan, Wad El Faki had learned recitation in classical Arabic, voice control and correct pronunciation. According to El Sirr A. Gadour, Wad El Faki "did not belong to any of the main ethnic communities in Omdurman. This freed him from a narrow identity and made him a 'general' singer, crossing the tribal barrier to broader national affiliation."[9]

Hageeba started as essentially vocal music, sung by a lead singer and a chorus, with percussion coming from the tambourine-like tar frame drum. It was performed at weddings and other social occasions and soon became popular. – During the 1930s, the first commercial 78 rpm gramophone records of Sudanese musicians such as Muhamad Ahmed Sarour and Khalil Farah were recorded in Cairo and marketed from Omdurman, from where this new music spread to listeners in greater Khartoum and other urban centres.[29][30]

1930s – 1950s: rise of popular music through records, radio and music halls[edit]

Since the mid-1920s, modern instruments such as pianos, accordions and violins, as well as records and record players were imported.[g] In the 1930s, a number of music companies opened in Sudan, among them the Gordon Memorial College musical company. One of its members, called Mohamed Adam Adham, composed the piece Adhamiya, one of the earliest formal Sudanese compositions, that is still often played.[31]

The pioneers of this era were often singer-songwriters, including the prolific Abdallah Abdel Karim, called Karouma,[32] the innovative Ibrahim al-Abadi and Khalil Farah,[33] a poet and singer, who wrote the lyrics and music for the patriotic song Azza fi Hawak and was active in the Sudanese national movement.[34][35] Al-Abadi was known for an unorthodox style of fusing traditional wedding poetry with music. Further, a specific style of rhythmic choral singing by Sudanese women evolved out of praise singing during the 1930s, called Tum Tum. Originating from Kosti on the White Nile, the lyrics of tum tum were romantic, but sometimes also talking about the difficulties of female life. The music was danceable and became quickly popular in urban centres.[36]

The 1940s saw an influx of new names due to the rise of music programmes at Radio Omdurman.[37] Notable performers included Ismail Abdul Mu'ain, Hassan Attia and Ahmed al Mustafa. Another singer-songwriter was Ibrahim al Kashif, who was called the Father of modern singing. Al Kashif sang in the style of Mohamed Ahmed Sarour, a pioneer of hageeba, and relied on what Abdel Karim Karouma had started, renewing popular singing styles. For live performances, there were also two dance halls in Khartoum, St James' and the Gordon Music Hall.[38]

Subsequently, Sudanese popular music evolved into what is generally referred to as "post-hageeba", a style dominating in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. This period was marked by the introduction of instruments from both East and West, such as the violin, accordion, oud, tabla or bongo drums. Further, a big band style with a string section and brass instruments came into existence. Post-hageeba music, mixed with Egyptian and Western elements has also been called al-aghani al-hadith (modern songs).[39]

1960s – 1980s: the Golden Age of popular music in Sudan[edit]

In the 1960s, American pop stars became well known, which had a profound effect on Sudanese musicians like Osman Alamu and Ibrahim Awad, the latter becoming the first Sudanese musician to dance on stage.[40] Under these influences, Sudanese popular music saw a further Westernisation and the introduction of electric guitars and brass instruments. Guitar music also came from the South of the country, and was played like the Congolese guitar styles. Congolese music like soukous, as well as Cuban Rumba, exerted a profound influence on Sudanese popular music.[41]

Starting his career in the late 1950s, the Nubian singer, songwriter and instrumentalist Mohammed Wardi became one of Sudan's first superstars. Despite his exile following the military coup in 1989, his popularity in Sudan and beyond kept rising until his return in 2002 and up to his death in 2012.[42]

Singer-songwriter Sayed Khalifa was one of the first Sudanese musicians trained in formal music theory, which he acquired at the Arab Music Institute in Cairo during the early 1950s. Like other Sudanese singers, he performed in both Standard Arabic as well as in the Sudanese form of Arabic, thus appealing both to the educated elite and to the common people. Khalifa is known for his songs Ya Watani (My Homeland) and Izzayakum Keifinnakum (How are you?).[43]

Performing from the late 1970s onward, a new popular singer was Mostafa Sid Ahmed. A teacher as a young man, he entered the College of Fine Arts and Music in Khartoum and composed his music to the lyrics of many well-known Sudanese poets like Azhari Mohamed Ali and Mahjoub Sharif, often expressing the longing for freedom and the struggle of the Sudanese people against dictatorship.[44]

An important development in modern Sudanese music was introduced by the group Sharhabil and his band – formed by a group of friends from Omdurman – namely Sharhabil Ahmed[41] and his fellow musicians Ali Nur Elgalil, Farghali Rahman, Kamal Hussain, Mahaddi Ali, Hassan Sirougy and Ahmed Dawood. Sharhabil's wife and member of the band, Zakia Abdul Gassim Abu Bakr, was the first female guitarist in Sudan.[45] They introduced modern rhythms relating to Western pop and soul music, using electric guitars, double bass, and jazz-like brass instruments, with an emphasis on the rhythm section. Their lyrics were also poetic and became very popular. Up to the late 2010s, Sharhabil's band has been one of the leading names in Sudanese music, performing both at home as well as internationally. Another popular group of the late 1970s were called 'The Scorpions and Saif Abu Bakr'.[46]

Since the 1940s, women had slowly become socially acceptable on the musical scene: Well-known singers were Um el Hassan el Shaygiya and most of all, Aisha al Falatiya, who as early as 1943 was the first woman to sing on Sudanese radio. Another outstanding female singer and political activist of the years before and after Sudan's independence in 1956 was Hawa Al-Tagtaga, who left a long lasting influence for the "moral and cultural legitimacy she bestowed on younger generations of Sudanese women singers who follow her tradition", as critic Magdy El Gizouli put it.[47]

During the 1970s, a wave of new women's groups became prominent on stage and the radio. Most famous among these was a band composed of three sisters called Al Balabil (transl.: The Nightingales). They formed as a band in 1971, appeared on many live and TV shows and became very popular across East Africa.[48][42] The 1980s saw the rise of Hanan Bulu Bulu, a singer whose performances were deemed by some as sensual and provocative. She was repeatedly detained by the authorities and even beaten up by hardliners.[49]

International popular genres like Western dance music, rock or pop music and African-American music have had a profound effect on modern Sudanese music. As in other African countries, one of these influences were the military brass bands. Playing in such bands attracted many young military recruits, who later carried their newly learned music style and instruments over to popular music. The result was a kind of dance music, referred to as (Sudanese) jazz, which was not related to the American style of jazz, but similar to other modern dance music styles throughout East Africa. Prominent band leaders in this era include Abdel Gadir Salim and Abdel Aziz El Mubarak, both of whom have achieved international fame and distribution of their albums.[39]

In retrospect, the 1960s up to the 80s were called 'The Golden Age of Sudanese popular music'.[50] This period was documented by re-issued albums in 2018, when researchers from the US and Germany were looking for still existing recordings from that era. Out of this research, several digitised albums of popular music from Sudan were digitally remastered.[51] These included stars like Abdel Aziz El Mubarak, Kamal Tarbas, Khojali Osman, Abu Obeida Hassan,[52] Kamal Keila, Sharhabil Ahmed, Hanan Bulu Bulu, Samira Dunia and, most famously, Mohammed Wardi and have become available on the international market.[53]

A special place among musicians from Sudan can be granted to composer, musician and music director Ali Osman, who settled in Cairo in 1978 and became one of the important figures in Egypt for classical and contemporary music in the European tradition. After his beginnings in Sudan as a self-taught rock musician, he later turned to classical music and composed symphonic works of Sudanese or Egyptian inspiration that have been performed internationally.[54]

1990s – 2000s: restrictions through sharia law and the decline of popular music[edit]

After a military coup in 1989, the imposition of sharia law by an Islamist government brought about the closing of music halls and outdoor concerts, as well as many other restrictions for musicians and their audiences. Many of the country's most prominent musicians or writers were barred from public life, and in some cases even imprisoned. Others, like Mohammed al Amin, whose personal style of playing the oud influenced other musicians,[55] and Mohammed Wardi, took exile in Cairo or other places.[56] Traditional music suffered too, with East African zār ceremonies, where women conjure and exorcise evil spirits through music and dance, interrupted and deemed as 'pagan'.[57] In this context of ceremonies for women, the singer Setona, born in Kordofan and raised in Khartoum, before she emigrated to Cairo in 1989, published two albums, called Tariq Sudan and Queen of Hena, with some of her songs related to henna ceremonies.[58] Another singer and composer of popular songs, who appeared on Sudan's musical scene in the 1990s, is Nada Al-Qalaa. Through her songs, video clips and media interviews, Al-Qalaa has presented conservative views on social life and gender roles. This and the support by wealthy patrons in Sudan and Nigeria has caused criticism, accusing her of being close to the military government. On the other hand, her music and public appearance has earned her a wide following for more than twenty years.[59]

The popular singer Abu Araki al-Bakheit was banned from performing his political songs, but eventually managed to continue performing in defiance of the authorities[60] and had a comeback in 2019 during the Sudanese revolution.[61] Others, like the southern Sudanese singer Yousif Fataki had all their tapes erased by Radio Omdurman. Other performers that continued to be popular during this time include Abdel Karim al Kabli or Mahmoud Abdulaziz, both with a notably long and diverse history of performance and recordings, as well as Mohammed al Amin and Mohammed Wardi.[62] Occasionally accompanying Wardi and poetry recitals, blind oud player Awad Ahmoudi has been known for his distinct style of playing the oud in his typical style and pentatonic scales.[63]

Another musician, who started his career in the late 1980s and also suffered from harassment by the military government, is Omer Ihsas. A native of southern Darfur, he and his band have played and spread their message of peace and reconciliation both in camps for internally displaced people in Darfur, as well as in Khartoum and on international stages.[64]

Foreign musicians, who became popular in Sudan, included reggae superstar Bob Marley and American pop singer Michael Jackson, while the funk of James Brown inspired Sudanese performers such as Kamal Keila.[65] The spread of international pop music through radio, TV, cassette tapes and digital recordings also prompted a growing number of Sudanese musicians to sing in English, connecting their music with the outside world. – Even though the government of the time discouraged music, dance and theatre, the College of Music and Drama of Sudan University of Science and Technology in Khartoum, in existence since 1969, continued to offer courses and degrees, thus giving young people a chance to study music or theatre.[66]

2000s – present[edit]

Protest songs, reggae, hip hop and rap[edit]

Songs with political messages have been popular in Sudan since at least the 1960s. Political lyrics by poets and musicians such as Mohammed Wardi's "Green October" or Mohammed Al-Amin's song "October 21st" became famous in the context of the October 1964 Revolution.[67] Ever since the third Sudanese Revolution started in December 2018, musicians, poets and visual artists have been playing an important part in the mainly youth driven movement.[68][69] Referring to its impact at the sit-in outside the Sudanese army headquarters on April 25, 2019, 'Dum' (trans. 'blood'), a song by Sudanese-American rap musician Ayman Mao was called the "Anthem of Sudan's Revolution".[70][71] According to Sudanese blogger Ola Diab, "young urban musicians have used their musical talents and creativity to express the revolt of protesters against President Al Bashir and his regime."[72][73]

As in other countries, reggae, rap or hip hop music combines local talents and international, young audiences, both in live performances as well as on the internet. In 2018, Sudanese journalist Ola Diab published a list of contemporary music videos by upcoming artists, both from Sudan and the Sudanese diaspora in the US, Europe or the Middle East.[74] One of them is the Sudanese–American rapper Ramey Dawoud and another the Sudanese–Italian singer and songwriter Amira Kheir.[75]

International artists, such as the popular Australian hip hop musician Bangs, who was born in Juba, South Sudan, see these genres as an avenue for peace, tolerance, and community for millions of African youth, who are powerful in numbers but politically marginalised. As the example of South Sudanese singer Emmanuel Jal shows, the lyrics have the ability to reach even child soldiers to imagine a different lifestyle.[76] Jimmie Briggs, the author of the book Innocence Lost: When Child Soldiers Go to War (2005) concurred: "A music group is not an army, but it can get powerful social messages out before trouble starts."[77]

Urban contemporary music of the 21st century[edit]

Since producing music in recording studios, using modern instruments and digital media, has become available in Sudan, growing numbers of people are listening to private (online) radio stations like Capital Radio 91.6 FM or are watching music videos.[78] As in other countries with restrictions of freedom of expression, the use of smartphones offers especially young, urban and educated people, and most importantly, Sudanese women, a relatively safe space for exchange with their friends or distant relatives, as well as access to many sources of entertainment, learning or general information.[79]

Until the Sudanese Revolution of 2018/19, permission for public concerts had to be obtained by the Ministry of Culture as well as by the police, and after 11 pm, all public events had to end. As the mostly young audiences did not have enough money to pay for tickets, most concerts, for example in the National Theatre in Omdurman, the garden of the National Museum of Sudan or the Green Yard sports arena in Khartoum, were offered free of charge. Musical performances were also organized in the premises of the French, German or British Cultural centres, giving young artists a chance to perform in a sheltered environment. Workshops with visiting artists and festivals like the Karmakol International Festival or the Sama Music Festival have given opportunities to young Sudanese musicians to improve their skills and experience.[80][81][82]

Famous local artists of this era are the musicians of Igd al-Jalad, a group known for its critical expression for many years,[49][83] the popular singer Nancy Ajaj and the pop group Aswat Almadina,[84] all of them singing more or less obvious lyrics about their love of the country, which they claim as their heritage and future, despite the ruling government of the time. Another popular musician is Mazin Hamid, who became known as producer of music videos and through his live performances as singer, guitarist and composer.[85] Islam Elbeiti is a young Sudanese female bass player, radio presenter, and social change activist.[86] As members of the important group of the Sudanese diaspora, Alsarah & The Nubatones, Sinkane or the rapper Oddisee are examples for musicians with a Sudanese background living in the US.[87]

Following their musical studies at Ahfad University for Women in Omdurman, as well as by participating in workshops and concerts at the German cultural institute in Khartoum, a band of young women called Salute yal Bannot ('Respect for the girls') became well known in 2017.[88] Their song African Girl[89] has scored more than 130,000 views on YouTube alone and earned them an invitation to the popular music show Arabs Got Talent in Beirut. After leaving this band, one of their lead singers, composer and keyboard player Hiba Elgizouli has been pursuing her own career as a singer-songwriter and produced her own music videos.[90]

A new trend in Sudanese urban music since the 2010s is called Zanig and has become popular as a form of underground music, spread through bootleg recordings, live shows and sound systems on public transport. It was described in the following way by cultural journalist and fellow of the Rift Valley Institute, Magdi el Gizouli:

This bootleg musical genre, pioneered by the King Ayman al-Rubo, is a fusion of West African beats and Egyptian mahrajanat style, with frequent accelerations and deceleration and techno-style repetition. Zanig queens sing about "antibaby pills" and the agency of "MILFs" and introduce themselves with maxims like: "If you follow the sugar mummies you'll end up driving six cars, and if you follow the little buds you'll waste your money in restaurants".[91]

In 2020, a local branch of the Arabic Oud House (Bayt al-Ud al-Arabi) was opened in Khartoum, dedicated to teaching the Arabic musical instruments oud and qanun as well as classical Arabic musical tradition, and as a centre for events and exchange.[92] The Arabic Oud House is a network of musical centres, started by renowned Iraqi oud player and composer Naseer Shamma, with headquarters in Cairo and branches in Alexandria, Egypt, as well as in Constantine, Algeria and Abu Dhabi, UAE.[93]

In 2022, a new band from Port Sudan called Noori & his Dorpa Band published music videos and an album for Ostinato records.[94] Their music is inspired by traditional and modern music of the Beja people, using a traditional tanbura (lyre) combined with an electric guitar as well as saxophone, electric guitars and a rhythm section.[95]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Archaeologists of the British Museum found so-called rock gongs from prehistoric times, that are thought to have been used as instruments in social activities by civilizations that lived near the Nile. See the video by The British Museum in the following reference.[4]

- ^ The University of Khartoum's Institute for African and Asian Studies has a department for musicology with a large collection of visual, sound and written material.[5]

- ^ Through his concerts and recordings for Western music labels, the late composer and oud player Hamza El Din became internationally known. He was of Southern Egyptian Nubian origin, and sang both in his native dialect of Sudanese Arabic as well as in the Nubian language.[11]

- ^ As early as 1874, the German traveller Gustav Nachtigal reported that the Turkish Governor-General's army band played European anthems, marches and dances in his honour. Source: Gustav Nachtigal Sahara and Sudan. Translated from the original German with an introduction and notes by Allan G. B. Fisher and H. J. Fisher. Volume IV: Wadai and Darfur, p. 394. London-New York-Berkeley. 1971-1987

- ^ For a concise and well-researched overview of the origins and later developments of haqeeba music, as well as some links to contemporary, electronic versions, see the webpage by Sudanese cultural platform 'Locale' and musician Sammany Hajo.[27]

- ^ "Madīḥ means praise, praise poem, glorification and, in this context, praise hymn in honour of Allah and the Prophet Muhammad. One of the most famous madīḥ traditions in northern Sudan can be traced back to its founder Hajj El-Mahi, who lived in Kassinger near Kareima from c1780 to 1870. He is said to have composed about 330 religious poems that continue to be sung with an accompaniment of two ṭar. His descendants still cultivate this tradition. The song texts often reveal rapturous religiosity or moral intent. Their performance is part of private celebrations or public festivities, and can also be heard in the streets of the markets."[28]

- ^ "Records, record players and the new instruments have been sold in Khartoum since 1925. In 1931 recordings were produced in Cairo for Serror and Khalil Farah, the latter accompanied by lute, piano and violin. These recordings quickly became popular in coffee shops in Khartoum. This popularity encouraged businessmen to produce more records with Sudanese singers, including Ibrahim Abdul Jalil, An-Naim Mohammed Nur, Karoma, Al-Amin Burhan, Ali Shaigui, and the female singers Mary Sharif, Asha Falatiya and Mahla al-Abadiya. They were accompanied by lute, accordion, piano, violin, flute, riqq, ṭabla and, later, bongos. Other famous artists of that epoque were Zingar, Ismail Abdel Mu'ain, Hassan Atya and Awonda." Source: Artur Simon (2001) "Sudan, Republic of" in Grove Music online, see under Further reading.

Reference notes[edit]

- ^ "Traditional music in Africa". Music in Africa. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Sikainga, Ahmad (2012), "A short history of Sudanese popular music", in Ryle, John; Willis, Justin; Baldo, Suliman; Madut Jok, Jok (eds.), The Sudan Handbook (digital ed.), London: Rift Valley Institute, pp. 243–253, ISBN 9781847010308

- ^ Verney, Jerome and Yassin, 2006, pp. 397-407

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: The British Museum (15 January 2016). "How to play an ancient rock gong". YouTube. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ University of Khartoum. "Institute of African and Asian studies".

- ^ Ahmed, AlRumaisa (1 May 2017). "Dr. Ali Al Daw: Music as Heritage". Andariya.com. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ In his report on the Nubian musician Dahab from 1973, ethnomusicologist Artur Simon gives a detailed description of the social and artistic aspects of traditional Nubian music and the changes it had undergone through modern society. See Simon, Artur (2012). Kisir and tanbura: Dahab Khalil, a Nubian musician from Sai, talking to Artur Simon from Berlin (in English and German). Simon Bibliothekswissen. ISBN 978-3-940862-34-1.

- ^ Sadie, Stanley, ed. (1995). "Sudan". The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Macmillan Publishers Ltd. pp. 327–331.

- ^ a b c Gadour, El Sirr A. (26 April 2006). "Sudanese singing 1908–1958". Durham University Community. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Plumley, Gwendolen Alice (1976). El Tanbur: The Sudanese lyre or the Nubian kissar. Town and Gown Press. ISBN 9780905107028.

- ^ "Hamza El Din, 76; musician popularized North Africa's ancient traditional songs". Los Angeles Times. 30 May 2006. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Al-waza : A musical instrument reflecting the Sudanese heritage". Khartoum Star. 5 September 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: CGTN Africa (16 January 2016), Waza trumpet returns as residents in Sudan's Blue Nile region mark end of harvest, retrieved 23 March 2021

- ^ "BBC - A History of the World - Object : Sudanese slit drum". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Kettle drum". MINIM-UK. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Carlisle, Roxane Connick (1975). "Women singers in Darfur, Sudan Republic". The Black Perspective in Music. 3 (3): 253–268. doi:10.2307/1214011. ISSN 0090-7790. JSTOR 1214011.

- ^ Evans-Pritchard, Blake (4 January 2012). "Female singers stir blood in Darfur". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Leigh, Amy (25 February 2021). "Darfur's Women 'Hamakat' elders revise songs for peace". Rights for Peace. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Malik, Saadia I. (2003). Exploring Aghani al-banat: A postcolonial ethnographic approach to Sudanese women's songs, culture, and performance (PhD thesis). Ohio University.

- ^ Al Safi, Ahmad. "Possession cults". Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "The Egyptian "zar" ritual". Qantara.de – Dialogue with the Islamic World. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Touma, Habib Hassan; Schwartz, Laurie (trans.) (1996). The music of the Arabs. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. p. 162. ISBN 0-931340-88-8.

- ^ Breu, Philipp. "The Sufis of Khartoum". Qantara.de – Dialogue with the Islamic World. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Kheir, Ala; Burns, John; Algrefwi, Ibrahim (5 February 2016). "The psychedelic world of Sudan's Sufis – in pictures". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Eyre, Banning (20 September 2018). "Ahmad Sikainga on the two Sudans". Afropop Worldwide. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Sikainga, 2012, p. 247

- ^ Locale & Sammany. "A Brief Introduction to Haqeeba". localesd.com. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ Simon, Artur (2001). Islamic religious song and music. Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.27077. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- ^ Sikainga, 2012, p. 249

- ^ Ille, Enrico (2019). "Sudan: Modern and contemporary performance practice". In Sturman, Janet Lynn (ed.). The SAGE international encyclopedia of music and culture. SAGE Publications, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-4833-1773-1. OCLC 1090239829.

- ^ "Sudanese singing 1908–1958". By: El Sirr A. Gadour. 15 December 2005. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006.

- ^ "Abdel Karim Karouma". Discogs. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Khalil Farah". Discogs. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Hassan, Soha (15 July 2019). "The Sudanese woman and the protest song". International Media Support. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Verney, 2006, p. 398

- ^ Sikainga, 2012, p. 249–250

- ^ Lavoie, Matthew. "The golden era of Omdurman songs". VOA News. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ El Hassan, Idris Salim. "Khartoum: A portrait of an African colonial city". Academia.edu. University of Khartoum.

- ^ a b Verney, 2006, p. 399

- ^ Verney, 2006, p. 400

- ^ a b Nkrumah, Gamal (18 August 2004). "Sharhabeel Ahmed: Sudan's king of jazz". Al-Ahram Weekly. Archived from the original on 20 September 2005. Retrieved 27 September 2005.

- ^ a b "Five songs that defined Sudan's golden era". Middle East Eye. 15 October 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ al Mubarak, Khalid (17 July 2001). "Obituary: Sayed Khalifa". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Vezzadini, Elena (May 2019). "Leftist leanings and the enlivening of revolutionary memory: Interview with Elena Vezzadini". Noria research. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "Interview with Sudan's first professional woman guitarist: 'The Ministry of Culture neglects Sudanese art'". Radio Dabanga. 22 June 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Eyre, Banning (20 September 2018). "New releases of Sudanese music". Afropop Worldwide. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ El Gizouli, Magdy (20 December 2012). "Sudan's hawa: The banat come of age". sudantribune.com. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ For an interview in English with two of the singers, see the video on Aljazeera: "The 'Sudanese Supremes'". Al Jazeera English The Stream. 21 June 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ a b Verney, 2006, p. 401

- ^ Sohonie, Vik (23 September 2018). "There was music on every corner of every street in Khartoum". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Hird, Alison (13 September 2018). "World Music Matters – Sudan's forgotten musical heritage revived with violins and synths". RFI. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Michaelson, Ruth (18 February 2020). "Sudan's accidental megastar who came back from the dead". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Two Niles to sing a melody: The violins & synths of Sudan". Ostinato Records. 14 September 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Metwali, Ati (25 February 2017). "Remembering Ali Osman: Composer, academic and conductor of Egypt's Al nour wal amal orchestra". Ahram Online. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ "Mohammed el Amin". sudanupdate.org. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Mohammed al Amin returned to Sudan in 1994 and Mohammed Wardi returned in 2003. See Verney, 2006, p. 400

- ^ Verney, 2006, p. 403

- ^ See the article on Setona in English at the bottom of the webpage by German cultural centre Iwalewa Haus: Salah M. Hassan, Setona: The native henna artist in a global, in Prince Claus Fund et al. (ed.) The art of African fashion. Africa World Press 1998. ISBN 0865437262

- ^ "The ongoing debate about the biography, career and femininity of singer Nada Al-Qalaa". Fanack.com. 22 November 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Romero, Angel (16 April 2018). "Artist profiles: Abu Araki al-Bakheit". World Music Central. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Sudan: Abu-Araki Al-Bakheet celebrates with sit-inners". allafrica.com. 22 April 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Verney, 2006, p.400

- ^ Shammat, Lemya (29 December 2020). "Awad Ahmoudi, Oud Virtuoso". ArabLit & ArabLit Quarterly. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Romero, Angel (17 October 2017). "Artist profiles: Omer Ihsas". worldmusiccentral.org. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ "Habibi Funk 008: Muslims and Christians, by Kamal Keila". Habibi Funk Records. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Sudan University of Science and Technology. "College of Music and Drama". drama.sustech.edu. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Elzahra Awad, Fatima (3 April 2019). "Sudanese Music Testifies to a long Revolutionary History". Andariya. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Elbagir, Yousra (22 March 2017). "Letter from Africa: How poetry is taking on state censorship in Sudan". BBC News. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "The Lyrical Revolution - Sudan Memory". www.sudanmemory.org. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Kushkush, Isma’il (4 June 2019). "'Blood,' the anthem of Sudan's revolution, takes on new meaning amid violent repression". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "The Lyrical Revolution - Sudan Memory". www.sudanmemory.org. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Diab, Ola (30 December 2018). "New 'Sudan Uprising' Tracks You Should Listen To". 500 Words Magazine. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Adel, Fady (18 May 2019). "10 Hip Hop tracks from the Sudanese Revolution". www.scenenoise.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Diab, Ola (15 October 2018). "10 Urban Contemporary Songs by Sudanese Artists You Should Listen To". 500 Words Magazine. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ "Amira Kheir Releases View From Somewhere". World Music Central. 28 July 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Ireland, Corydon (20 March 2008). "Conference brings out pacific potential of African hip-hop". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Briggs, Jimmie (2005). Innocents lost: when child soldiers go to war. Internet Archive. New York : Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00798-1.

- ^ Omnia Shawkat (8 November 2016). "Afrodiziac & impact interview with Ahmad Hikmat". Andariya Magazine. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Gaafar, Reem (13 February 2019). "Sudanese women at the heart of the revolution". Andariya magazine. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "Karmakol Festival Returns in December 2021". 500 Words Magazine. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ "Sama Music Campus Sudan 2018 – 2020". Global Music International. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Amplifying women's voices in Sudanese hip hop". NADJA. 10 May 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "The Beatles of Sudan: 200 songs banished from Khartoum to Norway · ArtsEverywhere". ArtsEverywhere. 21 September 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Aswat Almadina. "Home". aswatalmadina.com. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Salih, Atif Ali (15 September 2016). "كافيه شو - مازن حامد: حكاية موسيقية جديدة" [Café show - Mazin Hamid: A new musical story]. مونت كارلو الدولية / MCD (in Arabic). Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ British Council Sudan. "Artist of the month: Islam Elbeiti". sudan.britishcouncil.org. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Saed, Omnia (26 September 2016). "4 artists from the new school of Sudanese music speak on their search for home & identity". OkayAfrica. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Wagenknecht, Laura (8 September 2016). "'Respect to the girls'- meet Sudan's all-female band". DW.COM. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Music video by Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Goethe-Institut, Salute yal bannot "African girl", retrieved 12 November 2019

- ^ "Hiba Elgizouli". Music in Africa. 23 June 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ El Gizouli, Magdi (January 2020). "Mobilization and resistance in Sudan's uprising – From neighbourhood committees to zanig queens" (PDF). Rift Valley Institute (RVI). p. 4. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Bait Aloud - Khartoum". www.schoolandcollegelistings.com (in Arabic). Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "Abu Dhabi Fest Celebrates The Oud!". Al Bawaba. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ Noori & His Dorpa Band — Saagama (Beja Power! Electric Soul & Brass from Sudan's Red Sea Coast), retrieved 6 August 2022

- ^ "Noori & His Dorpa Band's "Beja Power": Defiant in the face of repression - Qantara.de". Qantara.de - Dialogue with the Islamic World. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

Works cited[edit]

- Sikainga, Ahmad (2012), "A short history of Sudanese popular music", in Ryle, John; Willis, Justin; Baldo, Suliman; Madut Jok, Jok (eds.), The Sudan Handbook (digital ed.), London: Rift Valley Institute, pp. 243–253, ISBN 9781847010308

- Verney, Peter; Jerome, Helen; Yassin, Moawia (2006). "Sudan. Still yearning to dance". In Broughton, Simon; Ellingham, Mark; Lusket, Jon (eds.). The Rough Guide to World Music: Africa & Middle East. London, New York: Rough Guides. pp. 397–407. ISBN 978-1-84353-551-5. OCLC 76761811.

Further reading[edit]

- Ahmed, Alrumaisa. (2017) Dr. Ali Al Daw: Music as heritage. Andariya Cultural Magazine

- al-Daw, Ali; Muhammad, Abd-Alla (1985). Traditional musical instruments in Sudan (in Arabic and English). Khartoum: Inst. of African and Asian Studies. OCLC 631658755.

- al-Fātiḥ, Ṭāhir. Anā Ummdurmān: tārīkh al-mūsīqá fī al-Sūdān الفاتح, طاهر (1993). أنا امدرمان: تاريخ الموسيقى في السودان (I am Omdurman: musical history in the Sudan ) (in Arabic). Khartoum. OCLC 38217171.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Badri, Leena. (2020) Behind the sounds of Sudan: Preserving and celebrating our musical history.

- Banning, Eyre. (2018). New releases of Sudanese music. Afropop Worldwide

- Ille Enrico (2019). Sudan: Modern and contemporary performance practice, In Sturman, Janet (ed.) The SAGE international encyclopedia of music and culture. p. 2094ff. ISBN 1483317749, 9781483317748

- Locale.sd. A brief introduction to hageeba, illustrated document and audio files on the role of hageeba music in Sudan

- Malik, Saadia I. (2003). Exploring Aghani al-banat: A postcolonial ethnographic approach to Sudanese women's songs, culture, and performance (PhD thesis). Ohio University.

- Elbagir, Yousra. Letter from Africa: How poetry is taking on state censorship in Sudan. BBC Africa

- Simon, Artur (2001). Sudan, Republic of. Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.27077. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Yāsīn, Muʻāwiyah Ḥasan. 2005. Min tārīkh al-ghināʼ wa-al-mūsīqá fī al-Sūdān. Omdurman: Markaz ʻAbd al-Karīm Mīrghanī al-Thaqāfī. ISBN 9994256750 OCLC 537408538 Three volumes in Arabic on the history of singing and music in Sudan.

External links[edit]

Selected discography[edit]

- The Rough Guide to the music of Sudan (2005)

- 330 records from Sudanese and South Sudanese musicians on discogs

- Two Niles to sing a melody: The violins & synths of Sudan

- Sounds of Sudan – Abdel Gadir Salim, Abdel Aziz El Mubarak, Mohamed Gubara

To audio files or music videos[edit]

- Audio files of 2022 album Beja power! Electric soul & brass from Sudan's Red Sea coast

- Selected music videos by Sudanese festival producer Randa Hamid

- Zikr at the Hamid El-Nil Mosque in Omdurman on YouTube

- Music and history in the two Sudans, podcast by Afropop Worldwide

- Five songs that defined Sudan's golden era, with links to music videos with English translation

- Audio files of a historical hageeba song by Abdel Karim Karouma, French National Library.

- Abu Obaida Hassan & his tambour: The Shaigiya sound of Sudan

- Jazz, Jazz, Jazz, The Scorpions & Saif Abu Bakr

- Muslims and Christians, Kamal Keila

- Original Sudanese tapes, Nagat Abdallah

- Sudan tapes – Al Balbil Solo

- The Rough Guide to the Music of North Africa, CD 1997

- Sudanese recording label Munsphone on discogs

- Annotated discography by sudanupdate.org

- Selected music videos with English translation and notes by The Sounds of Sudan on YouTube

- BBC Radio 4 on Sudan's newest generation of musicians (audio programme)

- Field recordings from 1980 of traditional music of the Gumuz ethnic group in Sudan's Blue Nile State

- Field recordings from 1980 of traditional music of the Ingessana and Berta peoples in Sudan's Blue Nile State

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch