Passaleão incident

| Passaleão incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

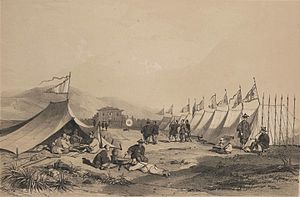

View of the Barrier Gate (Portas do Cerco) separating Macau and China (published 1842) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Vicente Nicolau de Mesquita | Xu Guangjin | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 36 men 1 howitzer | 400 men 20 cannons | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 wounded | 15 killed | ||||||

The Passaleão incident (Chinese: 關閘事件), also known as the Battle of Passaleão (or Pak Shan Lan[a]) or Baishaling incident, was a conflict between Portugal and China over Macau in August 1849. The Chinese were defeated in the only military confrontation, but the Portuguese called off further punitive measures after a naval explosion killed about 200 sailors.

Changes in Portuguese policy[edit]

The Portuguese governor João Maria Ferreira do Amaral had adopted a confrontational stance towards the Chinese, as displayed in the earlier revolt of the faitiões (October 1846). In early 1849 he proposed to extend a road from the walls of the city to the Chinese border. This required the relocation of some Chinese graves. Further, he ordered Chinese residents within the walls to pay taxes to the Portuguese authorities and no longer to the imperial mandarins.[2]

Amaral also placed stricter controls on the lorcha traffic and tried to stop the mandarins from collecting customary dues from the Tanka people who lived on boats in the harbour, since Macau was a free port. The mandarins retained two customs houses,[b] one at the Inner Harbour (Praia Pequena) and one at the Outer Harbour (Praia Grande). They refused to close them at Amaral's request, so on 5 March he proclaimed them closed. The mandarins still did not budge and, on 13 March, they were forcibly expelled. Amaral informed the mandarins of Zhongshan that if they ever visited Macau they would be received as foreign dignitaries.[3]

By all these moves the mandarins—and the Chinese state—stood to lose significant revenue. The Chinese inhabitants of Macau were inflamed. Placards offering a reward for the head of Amaral were posted in Guangzhou (Canton).[2] The governor, however, had achieved his goal of Macanese independence from China: for the legations of Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States accredited to China had chosen to stay in Macau while awaiting permission to enter China.[3]

Assassination of Amaral[edit]

Matters came to a head on 22 August, when Amaral and his aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Jerónimo Pereira Leite, left the town through the Portas do Cerco (Barrier Gate) to give alms to an elderly Chinese woman whom Amaral was supporting.[2] The two were only a few hundred yards within the gate when a Chinese coolie frightened Amaral's horse with a bamboo pole and signalled to his comrades in hiding. The one-armed governor held the reins with his teeth in order to draw his pistol. Before he could do so, he was set upon by seven Chinese, led by Shen Zhiliang and armed only with edged weapons, and dragged from his horse. Leite, also armed, was dismounted and fled on foot. Intending to collect the reward in Guangzhou, the assassins cut off Amaral's head and remaining hand as proof. The Portuguese authorities later retrieved the rest of his corpse and traced a trail of blood out of the gate.[3][4]

The assassination quickly became well known in Guangzhou, where the evidence was widely seen and the perpetrators openly bragged. When the Portuguese—supported by the Americans, British, French and Spanish—protested the assassins' escape to the Chinese government, the latter claimed complete ignorance of the event.[3]

Since Amaral had earlier dissolved the Senate of Macau (because it had opposed his imposition of taxes), there was a power vacuum after the assassination. Some senior officials requested assistance from Britain and the United States. The USS Plymouth and Dolphin took up defensive positions in the harbour, while HMS Amazon and Medea landed some Royal Marines to defend Portuguese civilians and British nationals.[3]

Battle of August 25[edit]

In the aftermath of the assassination, sensing Portuguese weakness, the Chinese moved troops closer to the city. On 25 August, the guns of the imperial fort of Latashi (拉塔石), known to the Portuguese as Passaleão,[5] about one mile north of the city, opened fire on the walls of Macau.[2] The field artillery and naval guns of the Portuguese returned fire, but could do little damage to the Chinese fort. With about 400 men and 20 cannons, the Chinese greatly outnumbered and outgunned the Portuguese garrison. In this situation, Vicente Nicolau de Mesquita, an artillery sub-lieutenant, volunteered to lead an attack on Baishaling with a company of about thirty-six men and a howitzer. The howitzer got off only one shot before its carriage broke down, but the shell caused a panic among the Chinese troops. Mesquita then led a charge, and the surprised Chinese broke and ran. Now in control of the fort but unable to hold it, Mesquita had the guns spiked and exploded the powder magazines.[2] One Portuguese was wounded and about 15 Chinese were killed.[6] Although Mesquita was treated as a hero in the twentieth century, both in Portugal and in Macau, he was not immediately recognised for the valour of his actions.[2]

To calm the Portuguese, Xu Guangjin, Viceroy of Liangguang, ordered the arrest of Shen Zhiliang, the lead conspirator. He was captured by officials in Shunde County, who also recovered Amaral's head and arm, on 12 September 1849. Although Xu believed that Amaral deserved his fate, he had Shen Zhiliang executed at Qianshan on 15 September.[4]

Aftermath[edit]

After their initial victory, the Portuguese received support from Britain, France and the United States. They brought in reinforcements from Portuguese India (Goa) and metropolitan Portugal (Lisbon). Following negotiations, the Chinese agreed to return Amaral's head and arm in January 1850, and the governor's entire body was returned to Lisbon for burial. The Portuguese proceeded to assemble a naval flotilla for a punitive expedition. The frigate Dona Maria II, the corvettes Irís and Dom João I and some armed lorchas gathered in the harbour on 29 October 1850 to fire a salute in honour of King Ferdinand II on his birthday. After the salute, and just before the local elites could board the Dona Maria II for the celebrations, the frigate exploded. The cause was sabotage by the keeper of the magazine with a grudge against the captain. Nearly 200 men died and the expedition was called off. A memorial to the victims of the Dona Maria II tragedy, erected in 1880, still stands by the site of the old fort in Taipa.[c][2]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Pak Shan Lan", "Pak-sa-leang" or "Pac-sa-leong" are renderings of the Cantonese pronunciation of 白沙岭, Mandarin "Baishaling". According to Carlos Augusto Montalto, the Portuguese called the battlement Passaleão.[1] The current name for the hill on which the ruins of the fort are located is Paotaishan (Chinese: 炮台山). Actual Baishaling (白沙岭) is a mountain ridge several kilometres north of Paotaishan.

- ^ The Chinese term, commonly encountered, for one of these is hoppo.

- ^ The original had the incorrect date "1848", but this was later corrected.

References[edit]

Sources[edit]

- Fei, Chengkang (1996). Macao: 400 years. Publishing House of Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences.

- Forjaz, Jorge (1996). Familias Macaenses. Macau: Instituto Português do Oriente. ISBN 972-9440-60-3.

- Garrett, Richard J. (2010). The Defences of Macau: Forts, Ships and Weapons over 450 Years. Hong Kong University Press.

- Montalto de Jesus, Carlos Augusto (1894). "Macao's Deeds of Arms" (PDF). The China Review. 21 (3). Hong Kong: China Mail Office: 158.

- Montalto de Jesus, Carlos Augusto (1902). Historic Macao. Hong Kong: Kelly & Walsh.

- Ride, Lindsay; Ride, May; Wordie, Jason (1999). The Voices of Macao Stones (PDF). Hong Kong University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Teixeira, Manuel (1958). Vicente Nicolau de Mesquita (2nd ed.). Macau: Tipografia "Soi Sang".

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch