Rolling and wheeled creatures in fiction and legend

Legends and speculative fiction reveal a longstanding human fascination with rolling and wheeled creatures. Such creatures appear in mythologies from Europe,[1] Japan,[2] pre-Columbian Mexico,[3] the United States, and Australia,[4] and in numerous modern works.

Rolling creatures[edit]

The triskelion is a motif with central symmetry used since ancient times. A variant with three human legs appears in the medieval flag of the Isle of Man. A variant with the head of Medusa in the union of the legs is associated with Sicily. It is not known the meaning it had in antiquity or its original Greek name.

The hoop snake, a creature of legend in the United States and Australia, is said to grasp its tail in its mouth and roll like a wheel towards its prey.[4] Japanese culture includes a similar mythical creature, the Tsuchinoko.[2]

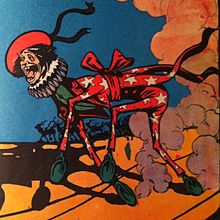

Buer, a demon mentioned in the 16th-century grimoire Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, was described in Collin de Plancy's 1825 edition of Dictionnaire Infernal as having "the shape of a star or wheel".[1] The 1863 edition of this book featured an illustration by Louis Le Breton, depicting a creature with five legs radially arranged.[5]

Neil R. Jones' 1937 story "On the Planet Fragment" features aliens dubbed the Disci, which are shaped like wheels, with limbs around the circumference. One of their methods of locomotion is a "rolling motion like that of a cartwheel."[6]

The 1944 science fiction short story "Arena", by Fredric Brown, features a telepathic alien called an Outsider, which is roughly spherical and moves by rolling.[7] The story was the basis for a 1967 Star Trek episode of the same name, and possibly also a 1964 episode of The Outer Limits entitled "Fun and Games", though neither television treatment included a spherical creature.[8]

E. E. "Doc" Smith's 1950 novel First Lensman features the fontema, which consists of two wheels connected by articulations to an axle, lives on sunlight, and has only two behaviors: rolling, and conjugation/mating, which is scarcely more complicated.

The Dutch graphic artist M. C. Escher invented a creature that was capable of rolling itself forward, which he named Pedalternorotandomovens centroculatus articulosus. He illustrated this creature in his 1951 lithograph Wentelteefje (also known by the English title Curl-up).[9][10]

A 1956 Scrooge McDuck comic, Land Beneath the Ground!, by Carl Barks, introduced Terries and Fermies (a play on the phrase terra firma), creatures who move from place to place by rolling. The Terries and Fermies have made a sport of their rolling abilities, causing earthquakes in the process.[11][12]

Northern Irish author James White's Sector General series features "Rollers" from the planet Drambo, doughnut-shaped aquatic organisms that do not have hearts, but which instead must roll continuously to maintain circulation by means of gravity.[13][14] The Rollers are described in the short story "Spacebird" in the 1980 edition of Ambulance Ship, and in other works in the series.[13][15][16]

The 1982 puppet-animated fantasy film The Dark Crystal, directed by Jim Henson and Frank Oz, introduced the character Fizzgig, a dog-like companion creature that rolls from place to place.[17] In 2015, an original film puppet of Fizzgig was put on auction with an estimated value of $12,000–$15,000.[18]

In The Citadel of Chaos (1983) by Steve Jackson, the reader encounters Wheelies, disc-shaped creatures with four arms who move by doing cartwheels.[19][20]

Tuf Voyaging, a 1986 science fiction novel by George R. R. Martin, features an alien called a Rolleram, described as a "berserk living cannonball of enormous size", which kills its prey by rolling over it and crushing it, before digesting it externally. Adults of the species weigh approximately six metric tons and can roll faster than 50 kilometres per hour (31 miles per hour).[21]

In the Sonic the Hedgehog video game series, which first appeared in 1991, the eponymous Sonic and his sidekick Tails are capable of moving by rolling.[22][23]

The 1995 short story "Microbe", by Kenyon College biologist and feminist science fiction writer Joan Slonczewski, describes an exploratory expedition to an alien world whose plant and animal life consists entirely of doughnut-shaped organisms.[24][25]

Wheeled creatures[edit]

Toy animals with wheels dating from the Pre-Columbian era were uncovered by archaeologists in Veracruz, Mexico, in the 1940s. The indigenous peoples of this region did not use wheels for transportation prior to the arrival of Europeans.[3]

L. Frank Baum's 1907 children's novel Ozma of Oz features humanoid creatures with wheels instead of hands and feet, called Wheelers.[26] Their wheels are composed of keratin, which has been suggested by biologists as a means of avoiding nutrient and waste transfer problems with living wheels.[9][27] Despite moving quickly on open terrain, the Wheelers are stymied by obstacles in their path that do not hinder creatures with limbs.[26] They also make an appearance in the 1985 film Return to Oz, based partly on Ozma of Oz.

The surrealist artist Remedios Varo (1908–1963) painted images of fantastical creatures with wheels as their bases, such as Homo rodans (1959),[28] Fantastic animal (1959),[29] and The Ladies at Bonhuer.[30]

The 1966 novella The Last Castle by Jack Vance describes "power-wagons" as creatures with a mix of biological and mechanical elements, including wheels.[31]

The 1968 novel The Goblin Reservation by Clifford D. Simak features an intelligent alien race that uses biological wheels.[32]

Kurt Vonnegut's 1973 novel Breakfast of Champions includes a brief description of fictional author Kilgore Trout's novel Plague on Wheels, which features a planet inhabited by sentient wheeled automobiles.

Evsise, the narrator of Harlan Ellison’s 1975 novelette "I'm Looking for Kadak", describes himself thus: "I am squat and round and move very close to the ground by a series of caterpillar feet set around the rim of ball joints and sockets on either side of my toches ... and when I’ve wound the feet tight, I have to jump off the ground so they can unwind and then I move forward again which makes my movement very peculiar ..."[33][34]

Chorlton and the Wheelies, a British stop-motion-animated television series that aired from 1976 to 1979, was set in "Wheelie World", which was inhabited by three-wheeled creatures called "wheelies".[35]

John Varley's 1977 short story, "In the Hall of the Martian Kings" feature several types of creatures on Mars with wheels (for locomotion) or spinning windmills.

Piers Anthony's 1977 book Cluster and its sequels feature aliens called Polarians, which locomote by gripping and balancing atop a large ball. The ball is a living, though temporarily separable, portion of the Polarian's body.[36]

David Brin's Uplift Universe includes a wheeled species called the g'Kek, which are described in some detail in the 1995 novel Brightness Reef.[37] In 1996's Infinity's Shore, a g'Kek is described as looking like "a squid in a wheelchair." The g'Kek suffer from arthritic axles in their old age, particularly when living in a high-gravity environment.[37][38]

A 1997 novel in the Animorphs series, The Andalite Chronicles, includes an alien called a Mortron, composed of two separate entities: a yellow and black bottom half with four wheels, and a red, elongated head with razor-sharp teeth and concealed wings.[39]

The 2000 novel The Amber Spyglass, by English author Philip Pullman, features an alien race known as the Mulefa, which have diamond-shaped bodies with one leg at the front and back and one on each side. The Mulefa use large, disk-shaped seed pods as wheels. They mount the pods on bone axles on their front and back legs, while propelling themselves with their side legs. The Mulefa have a symbiotic relationship with the seed pod trees, which depend on the rolling action to crack open the pods and allow the seeds to disperse.[40]

In the 2000 novel Wheelers, by English mathematician Ian Stewart and reproductive biologist Jack Cohen, a Jovian species called "blimps" has developed the ability to biologically produce machines called "wheelers", which use wheels for locomotion.[41][42]

The children's television series Jungle Junction, which premiered in 2009, features hybrid jungle animals with wheels rather than legs;[43] one such animal, Ellyvan, is a hybrid of an elephant and a van.[44] These animals traverse their habitat on elevated highways.[45]

The 2011 video game Dark Souls features Wheel Skeletons (or "Bonewheels"), which wear a wooden-spiked wheel, allowing them to roll at high speed.[46]

The 2021 Japanese children's stop motion animated series Pui Pui Molcar features guinea pig/vehicle hybrids. They are sentient, but are shown being driven around on roads by humans. Although they have wheels, they are usually shown using them like feet to walk and run.[47][48]

References[edit]

- ^ a b de Plancy, Jacques-Albin-Simon Collin (1825). Dictionnaire infernal (in French). P. Mongie aîné. p. 478. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ a b Pruett, Chris (November 2010). "The Anthropology of Fear: Learning About Japan Through Horror Games" (PDF). Interface on the Internet. 10 (9). Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Gambino, Megan (June 17, 2009). "A Salute to the Wheel". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Full, Robert; Earis, Kathleen; Wong, Mary; Caldwell, Roy (October 7, 1993). "Locomotion like a wheel?". Nature. 365 (6446): 495. Bibcode:1993Natur.365..495F. doi:10.1038/365495a0. S2CID 41320779.

- ^ de Plancy, Jacques-Albin-Simon Collin (1863). Henri Plon (ed.). Dictionnaire infernal (in French). Slatkine. p. 123. ISBN 978-2051012775. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ "Internet Speculative Fiction Database entry for "On the Planet Fragment"". www.isfdb.org. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- ^ Brown, Fredric (1944). Arena. Astounding Stories. ISBN 978-9635234974. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009.

- ^ Arena title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- ^ a b Scholtz, Gerhard (2008). "Scarab beetles at the interface of wheel invention in nature and culture?". Contributions to Zoology. 77 (3): 139–148. doi:10.1163/18759866-07703001. ISSN 1875-9866. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016.

- ^ Escher, Maurits Cornelis (2001). M.C. Escher, the graphic work. Germany: Taschen. pp. 14, 65. ISBN 978-3-8228-5864-6.

- ^ "Uncle Scrooge: Land Beneath the Ground!". Inducks Database. COA. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ "Terries and Fermies". Inducks Database. COA. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ a b White, James (1980). "Spacebird". Ambulance Ship. Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-345-28513-3.

- ^ Louie, Gary. "The Classification System". SectorGeneral.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017.

- ^ White, James (1997). Final Diagnosis. Tor Books. ISBN 978-0-8125-6268-2.

- ^ White, James (1999). Double Contact. Tor Publishing. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-7653-8986-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Creatures of Thra". DarkCrystal.com. The Jim Henson Company. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Woerner, Meredith (August 26, 2015). "Fizzgig puppet from Jim Henson's 'The Dark Crystal' up for auction". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Thomson, Neil. "Fighting Fantasy Reviewed - The Citadel of Chaos". RPGGeek. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Steve (1983). The Citadel of Chaos. ISBN 978-1-84831-076-6.

- ^ Martin, George R.R. (1986). Tuf Voyaging. Baen Books. ISBN 978-0-671-55985-4 – via Le Cercle Fantastique.

- ^ Sonic Team (June 23, 1991). Sonic the Hedgehog. Sega.

- ^ Thomas, Lucas M. (January 26, 2007). "Sonic the Hedgehog VC Review". IGN. IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016.

- ^ Switzer, David M. (March 11, 2014). "Microbe". The Science Fiction of Joan Slonczewski. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016.

- ^ Slonczewski, Joan (1998). "Microbe". The Children Star. Tor Science Fiction. ISBN 978-0-312-86716-4.

- ^ a b Baum, Lyman Frank (1907). Ozma of Oz. Oz. Vol. 3. John Rea Neill (illustrator). Chicago: The Reilly & Britton Co. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1-173-24727-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (April 14, 1983). "The Biology of the Wheel". Nature. 302 (5909): 572–573. Bibcode:1983Natur.302..572D. doi:10.1038/302572a0. PMID 6835391. S2CID 4273917.(Subscription required.)

- ^ "Homo rodans, 1959". WikiArt.org. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Fantastic animal, 1959". WikiArt.org. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "The Ladies at Bonhuer". Curiator.com. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Vance, Jack (1966). The Last Castle. Ace Books. ISBN 9781619470149. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ Simak, Clifford D. (1968). The Goblin Reservation. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 5, 42. ISBN 978-0-88184-897-7.

- ^ "I'm Looking for Kadak". The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- ^ "I Am [sic] Looking for Kadak". YouTube, Harlan Ellison reading the story. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- ^ "Chorlton and the Wheelies (1976 – 1979)". Toonhound.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2016.

- ^ Anthony, Piers (October 1977). Cluster. Avon Books. pp. 18–20, 143. ISBN 978-1-61756-013-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Brin, David (1995). Brightness Reef. Uplift trilogy. Vol. 1. Random House. ISBN 978-0-553-57330-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Brin, David (1996). Infinity's Shore. Uplift trilogy. Vol. 2. Easton Press. ISBN 978-1-85723-565-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ Applegate, K. A. (1997). The Andalite Chronicles. Animorphs. Scholastic Press. ISBN 978-0-590-10971-0.

- ^ Pullman, Philip (2000). The Amber Spyglass. His Dark Materials. Vol. 3. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-84673-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ Stewart, Ian; Cohen, Jack (2000). Wheelers. Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-52560-2 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Wheelers". Kirkus Reviews. September 15, 2000. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017.

- ^ "Disney success for Cornish company". BBC. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017.

- ^ Jungle Junction (2009– ) at IMDb

- ^ "The Treasure of Jungle Junction". Jungle Junction. Series 1. Episode 4a. October 3, 2009. Disney Channel. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ "Wheel Skeleton". Dark Souls Wiki. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- ^ "The Fans Have Spoken: Pui Pui Molcar Is the Best Anime of Winter 2021". Crunchyroll. February 16, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "『PUI PUI モルカー』ってなに!? Twitterで話題沸騰のパペットアニメ。いまなら最新話に追いつける!" (in Japanese). Famitsu. February 4, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch