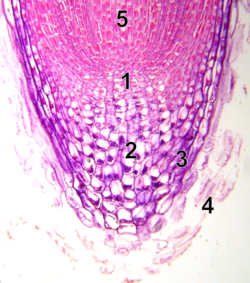

Root cap

The root cap (also called the calyptra) is a small but multitasking organ that covers the very tip of every growing plant root. It shields the delicate apical meristem from mechanical damage, lubricates the root's passage through soil, and houses specialised gravity-sensing cells that guide the root's overall direction of growth.

Structure and function

[edit]Root caps contain statocytes (gravity-sensing cells) whose dense statoliths settle in response to gravity; if the cap is carefully removed a root loses its orientation and grows at random. The cap also secretes a layer of mucilage that reduces friction and may foster signalling with the surrounding soil microbiota.[1] Because of its sensor cells, the organ underpins gravitropism (sometimes called geoperception), helping the root grow downwards with gravity or reorient upwards against it.[2][3]

Development and turnover

[edit]The root cap is renewed continuously. Stem-cell files on its inner face divide to generate successive layers of columella and lateral root-cap cells; as the root advances, the oldest outer layers are sloughed off so the organ maintains a steady size. In cereals and many legumes these discarded layers separate as long-lived "border cells", whereas in Arabidopsis thaliana most surface cells undergo rapid, developmentally-programmed cell death before shedding.[4]

Sensory roles and variation

[edit]Beyond sensing gravity, the cap acts as a broader signalling hub. Asymmetric redistribution of the plant hormone auxin in its statolith-bearing cells initiates curvature that restores the root to the gravity vector; related pathways also mediate water-seeking (hydrotropism) and help position future lateral roots, shaping overall root-system architecture.[4]

A true root cap is absent in some parasitic plants[5] and several aquatic plants, which instead form a thin, sac-like root pocket that performs a reduced protective role.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Raven, J.A.; Edwards, D. (2001). "Roots: evolutionary origins and biogeochemical significance". Journal of Experimental Botany. 52: 381–401. doi:10.1093/jexbot/52.suppl_1.381. PMID 11326045.

- ^ Burgess, Jeremy (1985). Introduction to Plant Cell Development. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521316118.

- ^ Kuya, Noriyuki; Sato, Seiichi (2011). "The relationship between profiles of plagiogravitropism and morphometry of columella cells during the development of lateral roots of Vigna angularis". Advances in Space Research. 47 (3): 553–562. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2010.09.009.

- ^ a b Kumpf, Robert P.; Nowack, Moritz K. (2015). "The root cap: a short story of life and death". Journal of Experimental Botany. 66 (19): 5651–5662. doi:10.1093/jxb/erv295. PMID 26068468.

- ^ Jeffrey, Edward Charles (2007). The Anatomy of Woody Plants. Pomeroy, Ohio: Carpenter Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-4067-1634-4.

- ^ Gupta, P.K. (2007). Genetics: Classical to Modern. Rastogi Publications. pp. 2–76. ISBN 978-8-1713-3896-2.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch