TIGIT

| TIGIT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | TIGIT, VSIG9, VSTM3, WUCAM, T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains, T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

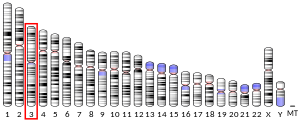

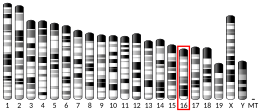

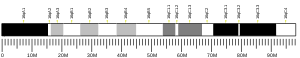

| External IDs | OMIM: 612859 MGI: 3642260 HomoloGene: 18358 GeneCards: TIGIT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TIGIT (/ˈtɪdʒɪt/ TIJ-it;[5] also called T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains) is an immune receptor present on some T cells and natural killer cells (NK).[6] It is also identified as WUCAM[7] and Vstm3.[8] TIGIT could bind to CD155 (PVR) on dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, etc. with high affinity, and also to CD112 (PVRL2) with lower affinity.[6]

Numerous clinical trials on TIGIT-blockade in cancer have recently been initiated, predominantly combination treatments. The first interim results show promise for combined TIGIT and PD-L1 co-blockade in solid cancer patients.[9] Mechanistically, research has shown that TIGIT-Fc fusion protein could interact with PVR on dendritic cells and increase its IL-10 secretion level/decrease its IL-12 secretion level under LPS stimulation, and also inhibit T cell activation in vivo.[6] TIGIT's inhibition of NK cytotoxicity can be blocked by antibodies against its interaction with PVR and the activity is directed through its ITIM domain.[10]

Clinical significance[edit]

TIGIT regulates T-cell mediated immunity via the CD226/TIGIT-PVR pathway.[11]

HIV[edit]

During Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, TIGIT expressing CD8+ T cells have been shown to be expanded and associated with clinical markers of HIV disease progression in a diverse group of HIV infected individuals.[12] Elevated TIGIT levels remained sustained even among those with undetectable viral loads. A large fraction of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells simultaneously express both TIGIT and another negative checkpoint receptor, Programmed Death Protein 1 (PD-1) and retained several features of exhausted T cells.[12] Blocking these pathways with novel targeted monoclonal antibodies synergistically rejuvenated HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses.[12] Further, the TIGIT pathway is active in the rhesus macaque non-human primate model, and mimics expression and function during Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV) infection.[12] This pathway can potentially be targeted to enhance killing of HIV infected cells during "Shock and Kill" HIV curative approaches.[13]

Cancer[edit]

TIGIT and PD-1 has been shown to be over-expressed on tumor antigen-specific (TA-specific) CD8+ T cells and CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from individuals with melanoma.[14] Blockade of TIGIT and PD-1 led to increased cell proliferation, cytokine production, and degranulation of TA-specific CD8+ T cells and TIL CD8+ T cells.[14] It can be considered an immune checkpoint.[11] Co-blockade of TIGIT and PD-1 pathways elicits tumor rejection in preclinical murine models.[15] Numerous anti-TIGIT therapies have entered clinical development.

- Tiragolumab

Tiragolumab is the furthest progressed anti-TIGIT therapy in development. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) setting, the phase II CITYSCAPE clinical trial (NCT03563716) evaluated the combination of the anti-TIGIT antibody tiragolumab in combination with the anti-PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab in patients with newly-diagnosed non-small cell lung cancer whose tumors expressed PD-L1. After a median follow-up of 16.3 months, the combination of tiragolumab and atezolizumab reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 38% compared to atezolizumab monotherapy. In a subset of patients with high PD-L1 expression (at least 50% of tumor cells expressing PD-L1), the combination of tiragolumab with atezolizumab further reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 71% compared to atezolizumab monotherapy. Overall, patients who received the combination of atezolizumab and tiragolumab lived a median of 23.2 months, compared to 14.5 months with atezolizumab monotherapy.[16] Despite this initial success, there was concern that the benefit of PFS in the tiragolumab + atezolizumab arm was driven by the underperformance of atezolizumab in this trial.[17] Another concern was that there was no link between TIGIT expression and the efficacy of tiragolumab in the trial.[18]

The phase III, randomized, double-blinded SKYSCRAPER-01 trial, which evaluates the efficacy of the combination of tiragolumab and atezolizumab in NSCLC patients whose tumors have high PD-L1 expression, failed to show a significant PFS improvement in the combination arm compared with placebo + atezolizumab, although it showed "a numerical improvement" in both endpoints of PFS and overall survival (OS).[19] In August 2023, an internal PowerPoint presentation detailing OS data of the second analysis was mistakenly made public on the Internet and showed a numerical improvement in terms of OS [estimated overall survival after a median follow-up of 15,5 months: 22,9 months in tiragolumab + atezolizumab arm versus 16,7 months in placebo + atezolizumab arm, HR: 0,81 (95% CI: 0,63, 1,03)].[20] No new safety signals were identified and the trial remains blinded to investigators and patients.[21]

Tiragolumab also shows encouraging efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma setting. In the MORPHEUS-liver trial, tiragolumab + atezolizumab + bevacizumab significantly improved response rate and PFS in both patients with positive PD-L1 expression and with negative PD-L1 expression.[22]

In small-cell lung cancer, tiragolumab didn't show any OS and PFS benefit in the SKYSCRAPER-02 trial,[23] but its development in SCLC setting is being continued as consolidation therapy for patients with limited-stage SCLC who have not progressed during/after chemotherapy and radiotherapy (NCT04308785).

In the Skyscraper-04 trial assessing the efficacy and safety of tiragolumab in patients who have recurrent, PD-L1 positive cervical cancer, the combination of tiragolumab and atezolizumab, although improved response rate in both PD-L1 low and PD-L1 high subgroups, only did so marginally and non-significantly.[24]

The combination of tiragolumab, atezolizumab, and platinum-containing chemotherapy improved PFS and OS compared with comparator arms in esophageal cancer patients in the phase II MORPHEUS-EC trial and the phase III SKYSCRAPER-08 trial.[25][26]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000181847 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000071552 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Lung Cancer and Immunotherapy with Dr. Patrick Forde and Oswald Peterson". YouTube. October 22, 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Yu X, Harden K, Gonzalez LC, Francesco M, Chiang E, Irving B, Tom I, Ivelja S, Refino CJ, Clark H, Eaton D, Grogan JL (Jan 2009). "The surface protein TIGIT suppresses T cell activation by promoting the generation of mature immunoregulatory dendritic cells". Nat Immunol. 10 (1): 48–57. doi:10.1038/ni.1674. PMID 19011627. S2CID 205361984.

- ^ Boles KS, Vermi W, Facchetti F, Fuchs A, Wilson TJ, Diacovo TG, Cella M, Colonna M (Mar 2009). "A novel molecular interaction for the adhesion of follicular CD4 T cells to follicular DC". European Journal of Immunology. 39 (3): 695–703. doi:10.1002/eji.200839116. PMC 3544471. PMID 19197944.

- ^ Levin SD, Taft DW, Brandt CS, Bucher C, Howard ED, Chadwick EM, et al. (April 2011). "Vstm3 is a member of the CD28 family and an important modulator of T-cell function". European Journal of Immunology. 41 (4): 902–15. doi:10.1002/eji.201041136. PMC 3733993. PMID 21416464.

- ^ Ge Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Sprengers D, Kwekkeboom J (2021-07-22). "TIGIT, the Next Step Towards Successful Combination Immune Checkpoint Therapy in Cancer". Frontiers in Immunology. 12: 699895. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.699895. PMC 8339559. PMID 34367161.

- ^ Stanietsky N, Simic H, Arapovic J, Toporik A, Levy O, Novik A, Levine Z, Beiman M, Dassa L, Achdout H, Stern-Ginossar N, Tsukerman P, Jonjic S, Mandelboim O (Oct 2009). "The interaction of TIGIT with PVR and PVRL2 inhibits human NK cell cytotoxicity". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106 (42): 17858–63. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10617858S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903474106. PMC 2764881. PMID 19815499.

- ^ a b Pharmaceutical Leaders Highlight Promise of TIGIT. Feb 2017

- ^ a b c d Chew GM, Fujita T, Webb GM, Burwitz BJ, Wu HL, Reed JS, et al. (Jan 2016). "TIGIT Marks Exhausted T Cells, Correlates with Disease Progression, and Serves as a Target for Immune Restoration in HIV and SIV Infection". PLOS Pathogens. 12 (1): e1005349. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005349. PMC 4704737. PMID 26741490.

- ^ Steven G. Deeks (July 2012). "HIV: Shock and Kill". Nature. 487 (1): 439–440. Bibcode:2012Natur.487..439D. doi:10.1038/487439a. PMID 22836995. S2CID 205073070.

- ^ a b Joe-Marc Chauvin, Ornella Pagliano, Julien Fourcade, Zhaojun Sun, Hong Wang, Cindy Sander, John M. Kirkwood, Tseng-hui Timothy Chen, Mark Maurer, Alan J. Korman, Hassane M. Zarour (April 2015). "TIGIT and PD-1 impair tumor antigen-specific CD8⁺ T cells in melanoma patients". J Clin Invest. 125 (5): 2046–2058. doi:10.1172/JCI80445. PMC 4463210. PMID 25866972.

- ^ Robert J. Johnston, Laetitia Comps-Agrar, Jason Hackney, Xin Yu, Mahrukh Huseni, Yagai Yang, Summer Park, Vincent Javinal, Henry Chiu, Bryan Irving, Dan L. Eaton, Jane L. Grogan (December 2014). "The Immunoreceptor TIGIT Regulates Antitumor and Antiviral CD8+ T Cell Effector Function". Cancer Cell. 26 (6): 923–937. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2014.10.018. PMID 25465800.

- ^ Cho BC, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Hussein M, Cobo M, Patel A, Secen N, Gerstner G, Kim DW, Lee YG, Su WC, Huang E (2021-12-01). "LBA2 Updated analysis and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) from CITYSCAPE: A randomised, double-blind, phase II study of the anti-TIGIT antibody tiragolumab + atezolizumab (TA) versus placebo + atezolizumab (PA) as first-line treatment for PD-L1+ NSCLC". Annals of Oncology. 32: S1428. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.10.217. ISSN 0923-7534. S2CID 245059452.

- ^ Adams B (2021-11-10). "Roche posts 'impressive' TIGIT combo lung cancer data, but trial deaths weigh down shares". Fierce Pharma. Retrieved 2023-10-13.

- ^ "Looking beyond Roche's Tigit bombshell". Evaluate.com. 2022-05-11. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ "[Ad hoc announcement pursuant to Art. 53 LR] Roche reports interim results for phase III SKYSCRAPER-01 study in PD-L1-high metastatic non-small cell lung cancer". www.roche.com (Press release). Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ "Another twist in the TIGIT saga". ApexOnco. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ "[Ad hoc announcement pursuant to Art. 53 LR] Roche provides update on Phase III Skyscraper-01 study in PD-L1-high metastatic non-small cell lung cancer". www.roche.com (Press release). Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Hsu CH, Li D, Burgoyne A, Cotter C, Badhrinarayanan S, Wang Y, Yin A, Rao Edubilli T, Gane E (2023-06-01). "Results from the MORPHEUS-liver study: Phase Ib/II randomized evaluation of tiragolumab (tira) in combination with atezolizumab (atezo) and bevacizumab (bev) in patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC)". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 41 (16_suppl): 4010. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.4010. ISSN 0732-183X. S2CID 259083998.

- ^ Rudin CM, Liu SV, Lu S, Soo RA, Hong MH, Lee JS, Bryl M, Dumoulin DW, Rittmeyer A, Chiu CH, Ozyilkan O, Navarro A, Novello S, Ozawa Y, Meng R (2022-06-10). "SKYSCRAPER-02: Primary results of a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of atezolizumab (atezo) + carboplatin + etoposide (CE) with or without tiragolumab (tira) in patients (pts) with untreated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC)". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 40 (17_suppl): LBA8507. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.17_suppl.LBA8507. ISSN 0732-183X.

- ^ Salani R (2023-11-05). "Efficacy and safety results from SKYSCRAPER-04: An open-label randomized phase 2 trial of tiragolumab plus atezolizumab for PD-L1-positive recurrent cervical cancer". medically.roche.com. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ Hsu CH (2024-01-18). "SKYSCRAPER-08: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of first-line tiragolumab + atezolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma". medically.roche.com. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ Sun JM (2024-01-18). "MORPHEUS-EC: a phase Ib/II open-label, randomized study of tiragolumab plus atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in patients with previously untreated locally advanced unresectable or metastatic esophageal cancer". medically.roche.com. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

Further reading[edit]

- Riquelme P, Haarer J, Kammler A, Walter L, Tomiuk S, Ahrens N, Wege AK, Goecze I, Zecher D, Banas B, Spang R, Fändrich F, Lutz MB, Sawitzki B, Schlitt HJ, Ochando J, Geissler EK, Hutchinson JA (2018). "TIGIT+ iTregs elicited by human regulatory macrophages control T cell immunity". Nature Communications. 9 (2858): 2858. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.2858R. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05167-8. PMC 6054648. PMID 30030423.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch