The Hare and many friends

"The Hare and many friends" was the final fable in John Gay's first collection of 1727.[1] It concerns the inconstancy of friendship as exemplified by a hare that lives on friendly terms with the farm animals. When the horns of the hunt are heard, she panics and eventually collapses exhausted, begging each of her acquaintances to help her escape. All give her different excuses, the last being a "trotting calf" who bids her "Adieu" as the hunters burst onto the scene. The poem won widespread popularity for some 150 years afterwards but, on a prose version appearing in a collection of Aesop's Fables, Gay's original authorship has gradually become forgotten.

The fable's history[edit]

The story appeared as the final poem in the book of fables written by John Gay at the royal suggestion for the instruction of Prince William, Duke of Cumberland. Soon after its publication in 1727, Gay's hopes of Court preferment were disappointed and the story was put about by his friends that the fable had a personal application. In particular, Jonathan Swift wrote how "Gay, the Hare with many friends, /Twice seven long years at court attends,” only to be let down.[2] Though the fable's correct title is "The Hare and many friends", this mythologising of the poet's misfortunes contributed to its often being misquoted as "The Hare with many friends". The mistake was perpetuated by the frequently reprinted biographical notice, originally written by David Erskine Baker for his The Companion to the Play-house (1764), in which it is so mentioned.[3]

The Fables as a whole went through repeated editions and were "translated into every European language",[4] besides a Latin version by Christopher Anstey.[5] "The Hare and many friends" stood out as a particular favourite and was frequently anthologised in addition. It also became a recitation piece. William Cowper was "reckoned famous" for his childhood performances in the 1730s, not long after the Fables first appeared.[6] At the other end of the century, it is mentioned as an accomplishment of Catherine Morland, the heroine of Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey, who learned it "as quickly as any girl in England".[7]

The fable's opening lines begin, in the manner of La Fontaine, with a proposition that is to be demonstrated by the story that follows, .

- Friendship, like love, is but a name,

- Unless to one you stint the flame.

The gentle irony intended here was lost on some later readers at the start of the 19th century. One objected in print that "this singular position cannot be reconciled with our experience of the two different qualities of these passions".[8] Another, a vicar's wife, was stirred to reply only in her commonplace book that “The British fabulist misleads the mind, /Friendship and love are better thus defined,” although her explanatory verses never saw publication.[9]

Though both objectors mention Gay's name as the author, confusion was soon to be sown by the inclusion of Gay's poem in collections of Aesop's fables. It is quoted in Samuel Howitt's illustrated A new work of animals, principally designed from the fables of Aesop, Gay and Phaedrus (1811), but no indication is given who was responsible for which fable appearing there.[10] Again, the poem is quoted with no acknowledgement of Gay's authorship in the 1875 collection of Aesop's fables illustrated by Ernest Griset.[11] A few years later Joseph Jacobs retold the story in prose under the title "The Hare with many friends" in his Aesop compilation of 1894. There it is given the moral "He that has many friends has no friends", based on Gay's opening: "'Tis thus in friendships; who depend/ On many, rarely find a friend". Jacobs also sentimentalises the ending, allowing the hare to escape from the hunters.[12] Although a note buried at the end of the book acknowledges that the fable was originally Gay's, the many reprintings of the prose version since have been unanimous in declaring Aesop as the fable's originator.

Gallery of illustrations[edit]

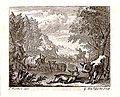

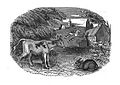

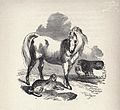

There have been several distinguished illustrators of the fable. They include Thomas Bewick. and possibly his brother John, as well as Bewick's pupil William Harvey. In addition, Samuel Howitt, who was acknowledged as the principal animal illustrator of his day, produced copperplates both for individual sale and as part of his A New Work of Animals. Ernest Griset's satirical prints restore a level of political caricature to the works he illustrates. Griset's apart, the majority of the prints show the exhausted hare lying at the foot of one or other of its apologetic friends; where it is the calf, there is a scene of hunters riding across the background.

- John Wootton, 1727

- Thomas Bewick, 1779

- Samuel Howitt, 1810

- John Bewick (attr) in an 1842 edition

- William Harvey, 1854

- Ernest Griset, 1875

References[edit]

- ^ Online text at Kalliope.org

- ^ John Heaneage Jesse, Memoirs of the Court of England, London 1843, Vol.3, pp.87-90

- ^ Vol.2, unpaginated

- ^ Frasers Magazine 17, 1838 p.196

- ^ Fabulæ selectæ auctore Johanne Gay latine redditæ, 1777

- ^ Charles Ryskamp, William Cowper of the Inner Temple, Cambridge University 1959, p.56

- ^ Jane Austen’s Complete Novels, p.603

- ^ Paul Ponder, Noctes atticæ, or Reveries in a garret (London 1825), p.153

- ^ Open University reading experience database

- ^ p.92

- ^ Online archive

- ^ pp.176-7

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch