Triadobatrachus

| Triadobatrachus Temporal range: Early Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Slabs of the fossil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Genus: | †Triadobatrachus Kuhn, 1962 |

| Species: | †T. massinoti |

| Binomial name | |

| †Triadobatrachus massinoti (Piveteau, 1936) | |

Triadobatrachus is an extinct genus of salientian frog-like amphibians, including only one known species, Triadobatrachus massinoti. It is the oldest member of the frog lineage known, and an excellent example of a transitional fossil. It lived during the Early Triassic about 250 million years ago, in what is now Madagascar.

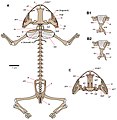

Triadobatrachus was 10 cm (3.9 in) long, and still retained many primitive characteristics, such as possessing at least 26 vertebrae, where modern frogs have only four to nine. At least 10 of these vertebrae formed a short tail, which the animal may have retained as an adult.[1] It probably swam by kicking its hind legs, although it could not jump, as most modern frogs can. Its skull resembled that of modern frogs, consisting of a latticework of thin bones separated by large openings.[2]

This creature, or a relative, evolved eventually into modern frogs, the earliest example of which is Prosalirus, millions of years later in the Early Jurassic.[3]

It was first discovered in the 1930s, when Adrien Massinot, near the village of Betsiaka in northern Madagascar, found an almost complete skeleton in the Induan Middle Sakamena Formation of the Sakamena Group. The animal must have fossilized soon after its death, because all bones lay in their natural anatomical position. Only the anterior part of the skull and the ends of the limbs were missing. This fossil was initially described under the name Protobatrachus massinoti by the French paleontologist Jean Piveteau in 1936.[4][5] Much more detailed description were published more recently.[1][6]

Although it was found in marine deposits, the general structure of Triadobatrachus shows that it probably lived for part of the time on land and breathed air. Its proximity to the mainland is further borne out by the remains of terrestrial plants found with it, and because most extant amphibians do not tolerate saltwater,[7] and that this saltwater intolerance was probably present in the earliest lissamphibians.[8]

Gallery[edit]

- CT-scan

- Diagram

- Cast

- Life restoration by N. Tamura

References[edit]

- ^ a b Ascarrunz, Eduardo; Rage, Jean-Claude; Legreneur, Pierre; Laurin, Michel (2016). "Triadobatrachus massinoti, the earliest known lissamphibian (Vertebrata: Tetrapoda) re-examined by µCT-Scan, and the evolution of trunk length in batrachians". Contributions to Zoology. 58 (2): 201–234. doi:10.1163/18759866-08502004.

- ^ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 56. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ^ Rocek, Z. (2000). "14. Mesozoic Amphibians". In Heatwole, H.; Carroll, R. L. (eds.). Amphibian Biology. Paleontology: The Evolutionary History of Amphibians (PDF). Vol. 4. Surrey Beatty & Sons. pp. 1295–1331. ISBN 0-949324-87-6.

- ^ Piveteau, J. (1936). "Une forme ancestrale des amphibiens anoures dans le Trias inférieur de Madagascar". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences. 202: 1607–1608.

- ^ Piveteau, J. (1936). "Origine et évolution morphologique des amphibiens anoures". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences. 203: 1084–1086.

- ^ Rage,J-C; Roček, Z. (1989). "Redescription of Triadobatrachus massinoti (Piveteau, 1936) an anuran amphibian from the Early Triassic". Palaeontographica Abteilung A. 206: 1–16.

- ^ Hopkins, G. R.; Brodie Jr, E. D. (2015). "Occurrence of Amphibians in Saline Habitats: A Review and Evolutionary Perspective". Herpetological Monographs. 29 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1655/herpmonographs-d-14-00006. S2CID 83659304.

- ^ Laurin, Michel; Soler-Gijón, Rodrigo (2010). "Osmotic tolerance and habitat of early stegocephalians: indirect evidence from parsimony, taphonomy, paleobiogeography, physiology and morphology". Geological Society of London, Special Publications. 339: 151–179. doi:10.1144/sp339.13. S2CID 85374803.

- Benes, Josef. Prehistoric Animals and Plants. Pg. 114. Prague: Artia, 1979.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch